Feeling and doing for homeless children

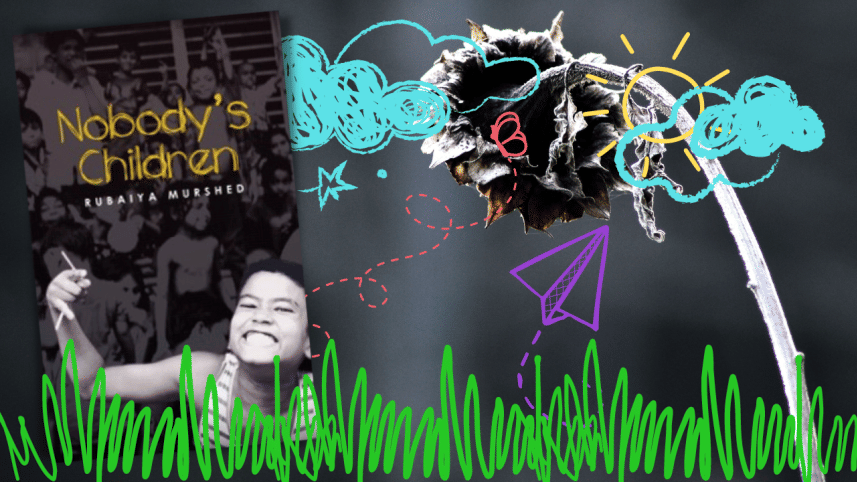

Rubaiya Murshed's Nobody's Children is a genre of its kind—it employs both stark facts and literary elements at the same time. As the title aptly suggests, it is focused on the issue of children who are living on the streets without proper care or support from their families.

One reading between the lines would unfailingly get tinged with the warmth and honesty of the author's feelings. To me, that is the most noteworthy thing about the book.

Its preface starts with a quote from the famous Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky: 'What is honour when you have nothing to eat'. Surely, it is a way of emphasising that necessities such as food and shelter are more important than abstract concepts like honour when it comes to survival and well-being. Only the victim knows how it hurts when one goes to sleep hungry or half-fed or how it feels to experience public negligence and scorn.

But Rubaiya, despite being an economist, does not reduce her characters to mere economic indicators like poverty, hunger, deprivation, and so on; instead, she makes a beautiful rendering of them in their totality.

A chapter titled "The Boy Who Loved" offers one such heart-touching example of a street boy named Saiful. He was once forced to take refuge in a bus stop near TSC in the Dhaka University campus.

"For street children like Saiful on such rainy nights", Rubaiya writes, "the only relatively dryer places to try and sleep are bus stands or under park benches". But Saiful, despite having no shelter and food security, exhibits a strong sense of affinity towards a beautiful yellow-beaked bird—an ochin pakhi, in his own words. As its wing breaks, we see how a frantic Saiful risks his own life to heal the bird, which was in the custody of a DMC student. Saiful camps outside the student's dormitory. It rains on and off all night, and he develops a high fever and pneumonia.

The bird cannot be saved, and Saiful cries out his heart for it, as if he were giving vent to all the frustrations and woes he has suffered since his birth.

Making others feel for them

Before joining the University of Dhaka, Rubaiya taught at the Sunnydale School, Dhaka for a few months. Sometimes as a proxy teacher, she shared the stories of the homeless children with class eight students and then asked them to write down whatever came to mind as they imagined themselves in the position of a homeless street child.

A part of Rubaiya thought that the children would feel bored by her approach. On the contrary, they wrote their impressions beautifully in their notebooks before tearing out the pages to hand over to her. The impressions of Fabiha Anbar, a student of Class Eight, Sunnydale School, go like this:

"Frankly speaking, I cannot even imagine myself as a homeless street child. We, the ones who have the privilege to stay with our families and enjoy the luxuries of life, are just so indulged in these that we never realise how important and valuable these things are. We just take everything for granted."

SDG and Rubaiya's effort

Eradicating poverty is a central theme of the SDGs, with Goal 1 specifically aimed at ending poverty in all its forms everywhere. The goal recognizes that poverty is not only a lack of income, but also a lack of access to basic services such as education, healthcare, and clean water. A lack of opportunity is not just an economic problem, but also a moral and ethical issue, Nobel laureate philosopher and economist Amartya Sen has argued. To him, access to education is a fundamental aspect of human development and a key driver of economic growth and prosperity.

Rubaiya, in her way, makes a commendable attempt to ensure that these children can have access to education through the bot-tola school she and her cohorts run for them.

Feeling the same way

In his poem 'Chimney Sweeper', published in his collection, Songs of Innocence, in 1789, William Blake reflects on the bleak and unjust conditions faced by child chimney sweepers in 18th-century England, who were often forced into dangerous and dirty jobs at a young age. Blake uses imagery and symbolism to critique the treatment of these children and highlight the innocence and purity that are lost as a result of their exploitation. The poem remains one of Blake's most widely read and studied works and is regarded as an important work of social criticism, an expression of the Romantic movement's concern for the oppressed and marginalised.

Both Rubaiya and Blake use their platforms to raise awareness about these issues and advocate for the betterment of these groups. Their actions demonstrate a strong sense of empathy and a desire to bring about change in society. Furthermore, both individuals show a willingness to challenge the status quo and speak out against the injustices they see in their communities.

This book, written in communicative and lucid prose, is a kind of docufiction, which is rapidly gaining popularity across the countries. It is a form of storytelling that uses real-life events, people, and places as the basis for a fictional or semi-fictional narrative. Rubaiya shows mastery in this particular genre. I hope her writer self will not be eclipsed by her researcher or economist self; rather, both will make a wonderful combination.

Protik Bardhan is a senior Sub-Editor at Prothom Alo.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments