Bangla in the age of algorithms

A phrase begins to circulate almost casually on a social media platform. By the next day, it is everywhere—spoken, typed, laughed over and argued about. The phrase is slightly absurd, two words fused in a way no dictionary has yet recorded, still instantly legible: “Chagol Kando.” Someone turns it into a meme. Journalists start using it in headlines. Within days, the words feel familiar, as if they had always belonged to Bangla.

This is how Bangla often evolves nowadays, not through official announcements or grammar books, but through social media, digital technology and moments of collective emotion. For over a millennium, the language has absorbed conquests, riots, religions, partition, and war. New words entered the daily vocabulary, pronunciations softened or hardened across regions, and grammar bent to usage.

Language is finely attuned to the world around it, shifting in small ways almost every day according to the prominent linguist and former Director General of Bangla Academy, Professor Monsur Musa. “Bangla has evolved over one and a half thousand years. With every political change comes an ideological shift, and the language evolves alongside it. For instance, during the recent July uprising, many new words entered the Bengali language. A great deal of graffiti appeared carrying words that had never existed before,” he said.

How has Bangla evolved: A brief history

Bangla belongs to the Indo-European language family and, like many major languages, its origins are debated. Linguists such as Suniti Kumar Chatterji and Sukumar Sen argued that Bengali emerged around the 10th century CE, evolving from Magadhi Prakrit in its spoken form and Magadhi Apabhramsha in its written form. A different view was proposed by Dr Muhammad Shahidullah and his followers, who placed the beginnings of Bangla earlier, around the 7th century CE, tracing its development to the spoken and written varieties of Gauda.

“Before the Aryans arrived, this region possessed a "Non-Aryan" (Anarya) culture. The arrival of the Aryans led to a fusion of these two groups, creating a "Sankar" (hybrid or mixed) culture and nation. This racial and cultural synthesis marked the beginning of the linguistic blending that would define Bangla,” explained Dr. Mohammad Ashaduzzaman, Professor in the Department of Linguistics, Dhaka University. From this point forward, the language began to be shaped by social, political, and economic factors, as well as by traders and religious missionaries who brought their own linguistic influences.

Around the time of the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the form of Bangla we recognise today began to take shape, drawing largely from the dialect spoken in the Nadia region. Over time, this dialect gained prominence and gradually formed the basis of modern standard Bangla.

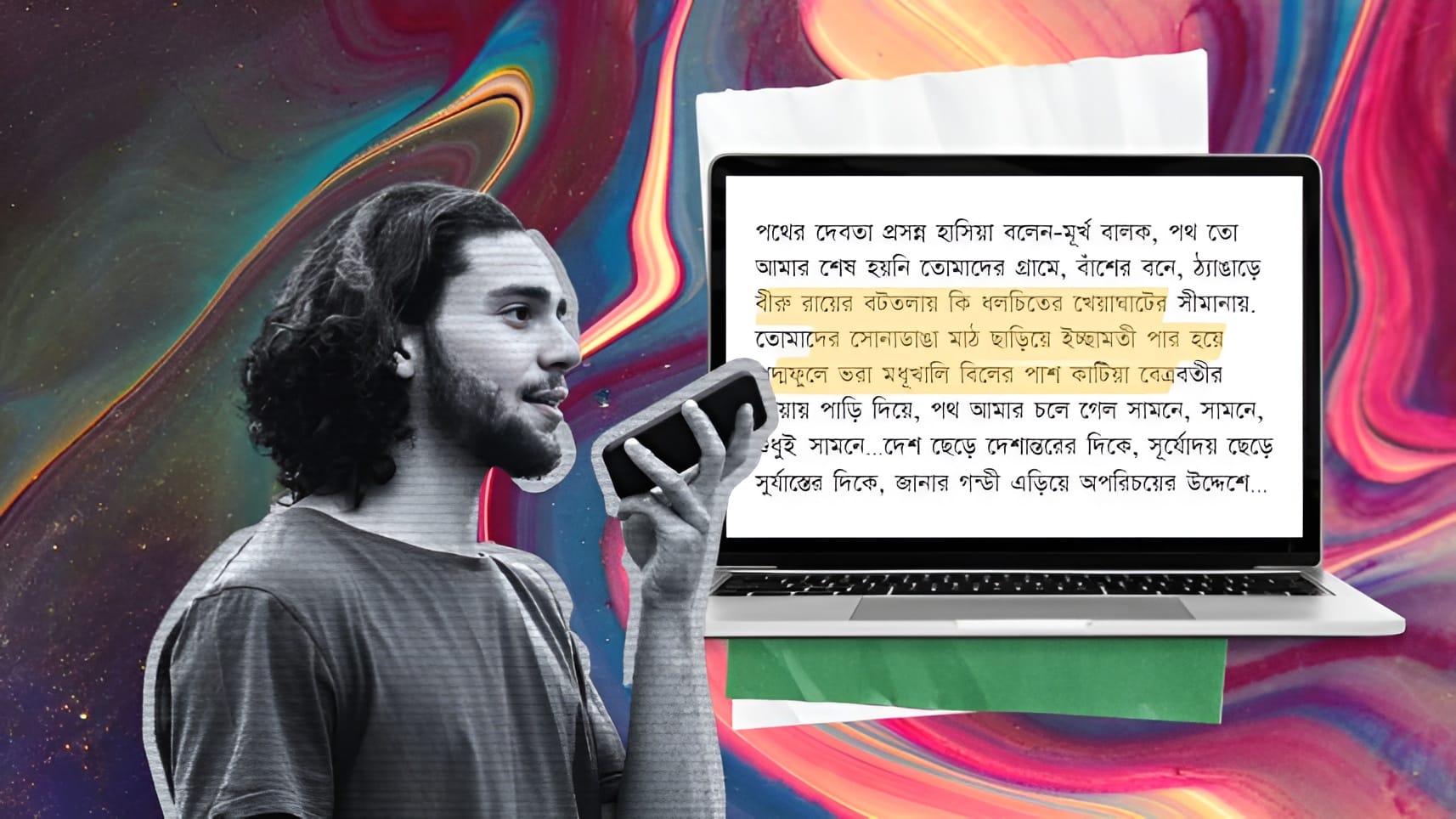

With the rise of generative AI and large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT or Gemini, we can now hold conversations with machines in Bangla. AI has begun to read, write, and even craft creative content in Bangla. For the first time in history, language evolution is partly being steered by machines trained on digital data. As this new voice enters our linguistic world, what will it mean for the language itself—for how we speak, shape, and pass it on?

How will AI influence the future of Bangla?

Historically, people were the primary drivers of the evolution of Bangla. Writers standardised forms and communities collectively decided what sounded “natural.” But in the 21st century, technology has also been a powerful co-author. Social media shortens expressions. Autocorrect nudges spelling choices. Search engines influence which words people use to find information.

Now, artificial intelligence (AI) has added a new layer. With the rise of generative AI and large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT or Gemini, we can now hold conversations with machines in Bangla. AI has begun to read, write, and even craft creative content in Bangla. We can turn to it with our questions in Bangla and receive instant replies.

For the first time in history, language evolution is partly being steered by machines trained on digital data. As this new voice enters our linguistic world, what will it mean for the language itself—for how we speak, shape, and pass it on? And what of young people, still learning Bangla, yet already turning to LLMs to converse in it?

“LLMs like ChatGPT or Gemini operate within a limited set of response patterns, typically around 10 to 20. When someone consults an LLM, or a student seeks educational help from it, their vocabulary and ways of expressing ideas can become confined to these fixed patterns. It can quietly guide how people write. Over time, these micro-influences accumulate,” mentioned Nishat Raihan, an LLM researcher at George Mason University. “Previously, if 20 different people tackled the same question, they would each bring unique expressions and approaches. Today, that richness of language and diversity of thought is at risk of narrowing, particularly among young people who rely on it heavily for assignments and homework.”

Many linguists share similar concerns, viewing these technological shifts through the lens of language use and creativity. “AI’s language is mechanical, and it is often quite noticeable whether an assignment or a piece of creative writing has been produced with AI. Bangla is a powerful language that can express a single idea in many different ways. As the use of AI increases, Bangla may gradually lose some of this multidimensional expressive capacity,” noted Dr. Tariq Manzoor, Professor in the Department of Bangla, Dhaka University.

The corpus crisis and the digital gap

One major obstacle for Bangla in this age of AI is the absence of a strong, comprehensive corpus. While English utilises systematic processes to track word frequency and evolution, Bangla lacks an official, systematically updated record.

“In the Oxford or Cambridge dictionaries, you’ll see that they systematically record new words as they are added to the language. In English, they maintain a corpus of the language, which allows them to track even small changes. By studying word frequencies, we can observe which words are increasing in use, which are declining, and which are disappearing from the language altogether. This is an efficient process to keep track of language changes,” explained Professor Musa.

Drawing on language change and language contact theories, Professor Musa highlighted how semantic changes, borrowing, and code-switching (alternating between languages in conversation) have become increasingly common. “Religion has played a significant role in recent language change. The usage of words related to religion has grown substantially. Currently, there is no system for officially adding new words, and we do not have any formal corpus. New words appear through newspapers, and we infer their meanings from context. Without an official corpus, Bangla currently lacks discipline, and many words are used incorrectly in the wrong context.”

This poses a major problem for the language in the age of LLMs, which are essentially “probability machines” trained on existing records. The absence of a clean digital corpus forces AI to rely on fragmented, messy, or outdated data. This is especially critical for a language that shifts rapidly during political upheavals; an AI trained six months ago may be “linguistically illiterate” to the new vocabulary emerging from events like the July uprising, for which no registration system currently exists.

Moreover, research shows that Bangla is one of the least used languages on the internet despite having such a vast number of speakers. English accounts for 54% of online language content, and the top 12 languages (English, Russian, German, Spanish, French, Japanese, Portuguese, Italian, Persian, Polish, Chinese, and Turkish) make up over 90% of all content, whereas Bangla constitutes less than 0.1% (Hernandez, 2019, p. 8). As of 2022, Bangla Wikipedia ranked 65th in the world. This is alarming, given that a substantial share of LLM training data comes from the internet.

On top of that, a large portion of Bangla text online is plagued by inconsistent spelling, grammatical errors, and irregular structure. Researchers often depend on Bangla Wikipedia and NCTB textbook data for training models, but these sources may not consistently guarantee high-quality inputs.

“Lack of high-quality data online is a major obstacle in training LLMs to perform reliably with Bangla prompts. We classify Bangla as a mid-tier resource language: the available data allows only somewhat acceptable performance. A lack of sufficient data forces reliance on low-quality sources, and AI trained on such data produces poor content, creating a negative feedback loop that further degrades future model performance,” noted Raihan.

To address this, LLM researchers recommend mechanisms such as reinforcement learning (RL) with human feedback, which help filter out incorrect outputs. RL techniques like GRPO (Group Relative Policy Optimisation) evaluate groups of responses relative to one another, improving overall accuracy, stability, and reliability of language generation.

The “power group” bias in data

Professor Monsur Musa points out yet another factor responsible for shaping language. “In our society, the most influential groups are the middle and upper-middle classes. They play a particularly significant role in shaping linguistic trends,” he explained. “In the past, we did not use as many Arabic or Persian words in our everyday speech, but recently their usage has noticeably increased.”

These same groups also have the largest digital footprint. They dominate social media platforms, blogs, and online forums, producing a disproportionate share of the written content that feeds today’s digital ecosystem. As a result, when AI systems are trained primarily on internet data, they inevitably learn and replicate their linguistic patterns, vocabulary choices, and worldview.

This creates a subtle but serious risk. The speech forms of rural communities, working-class populations, minority ethnic groups, and speakers of regional dialects are far less represented online. Their idioms, pronunciations, cultural references, and lived realities may not appear frequently enough in digital text to meaningfully shape AI training data. In the long run, the nuances, dialects, and expressive richness of millions could fade from the digital record, quietly erased from the linguistic future being shaped by algorithms.

Preparing Bangla for the AI age

Since the use of AI and LLMs will only grow in the future, the central challenge is to make Bangla fully compatible with the AI age so it does not fall behind. Raihan of George Mason University advocates developing LLMs dedicated solely to Bangla. “We need our own LLM model, which is exclusively trained on high-quality Bangla data. Even if the model is small—for instance, we trained a model with 1 billion parameters and nearly 9 billion Bangla words, which is very minimal compared to big LLMs. Still, its performance can be exceptional for Bangla prompts because it is trained only on Bangla data.”

Such models, he argues, help reduce the risk of distorting the language, producing incorrect spellings, or imposing English sentence structures on Bangla responses. However, training these models is expensive, and he emphasised that government support is essential to develop large-scale Bangla LLMs.

Moreover, building robust Bangla LLM requires a high-quality digital Bangla corpus—something Bangla still lacks. As Dr. Manzoor noted, “Some efforts to build a comprehensive and updated corpus have already begun through government initiatives. The challenge, however, is the limited number of skilled language teachers and experts in this field in our country, which inevitably slows the progress of such initiatives.”

He also stressed that publishing houses need to ensure that all their materials are uploaded in Unicode fonts and that digital reading options, such as eBooks, are developed alongside printed books. Clinging only to paper readership, he implied, is no longer realistic.

There is also a broader cultural issue. “We’re not language-conscious as a nation, unlike many countries that actively work on the development and stabilisation of their language,” observed Professor Musa. “Language will change, but if it keeps changing every day drastically, it will become incomprehensible. People from the same community will not be able to understand each other.” Promoting Promito (standard) Bangla in administration, education, and public life is essential to avoid such issues according to scholars.

Where English must be used, Professor Ashaduzzaman recommends prioritising transliteration to retain linguistic continuity. He also mentioned the ICT division’s project – Enriching the Bangla Language in Information Technology through Research and Development – that was launched in 2016.

Under this initiative, Bangladesh Computer Council was supposed to develop 16 tools, including a Bangla corpus, automatic translator from Bangla to the world’s 10 major languages, Bangla OCR (automatic recognition and composition of typed and handwritten text), speech-to-text and text-to-speech software, national keyboard (Bangla), Bangla font conversion engine, spelling and grammar checker, screen reader (software that automatically reads written text aloud), sentiment analysis software, keyboards for indigenous languages.

If properly implemented, the project would enable automatic composition of spoken Bangla, allow computer devices to read written text aloud, quickly convert printed books and documents into softcopy, provide accurate machine translation in Bangla, and build a comprehensive corpus of spoken and written Bangla. The project also envisioned developing more than nine software programmes compatible with Windows, Mac, and Linux, as well as more than seven apps for Android and iOS, aiming to strengthen Bangla’s global standing and advance Bangla’s recognition as an official language of the United Nations.

“Almost 10 years have passed, but barely any progress was made on that project. If this project is fully implemented, the status of Bangla could improve significantly, making the language more compatible with and resilient to the technological changes ahead,” remarked Dr. Ashaduzzaman of University of Dhaka.

Echoing this concern, Dr. Manzoor agrees that the challenge lies not in technology itself, but in institutional preparedness. “If we can establish proper processes, digital media and AI can strengthen Bangla and expand its usability. For example, we are still far behind in areas such as voice-to-text, text-to-speech, digital dictionaries, terminology development, translation, and conversion into IPA. This has to change for Bangla to thrive in the digital future,” he said.

Greater investment in Bangla-language AI research and model development is essential, with trained linguists, computer scientists, and social scientists working in close collaboration, supported by sustained government funding according to scholars. Ultimately, our collective actions will determine whether Bangla merely survives in the age of AI, or truly claims its place within it.

Miftahul Jannat is a journalist at The Daily Star. She can be reached at miftahul@thedailystar.net

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.