Why Upper House PR makes sense in today’s political climate

In Bangladesh's context, proportional representation (PR) is viable only for an Upper House (UH) within a bicameral legislature, with the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system retained for Lower House (LH). This would ensure historical continuity, voter-MP linkage, and electoral simplicity. With an Upper House allocated by PR based on a pre-disclosed party list, Bangladesh can create an inclusive oversight body on lawmaking that gives the opposition a tangible stake in parliament. However, this is not a cure-all for our governance woes, but it would pave the way for a much-needed check-and-balance mechanism in parliament.

Bangladesh's political trajectory vividly illustrates FPTP's distortions. Since 1991, small vote differences have produced huge seat gaps: in 2001, BNP won about 41 percent of votes but 193 of 300 seats, while Awami League (AL) won around 40 percent but only 62 seats; in 1991, a near tie (30.81 percent vs 30.08 percent) still gave BNP a 52-seat advantage; and in 2008, a 15-point vote lead resulted in an overwhelming parliamentary supermajority for AL (230 seats versus 30 for BNP). This dominance was later used to amend the constitution unilaterally, which led to the abolition of the non-party caretaker government through the 15th Amendment in 2011—plunging Bangladesh into an era of electoral authoritarianism that lasted until 2024. Time and again, FPTP has magnified the victory of the largest party far beyond its actual support, sidelining both voters and opposition parties.

These skewed outcomes led to political tensions and deadlock. When pluralities turn into landslides, "losers" feel shut out, and "winners" often govern with little regard for opposition voices, reinforcing zero-sum politics. The stakes under FPTP are so high that even a one-percent vote swing can flip a seat, encouraging desperate measures such as vote rigging, ballot stuffing, intimidation, and other electoral code violations. In this winner-takes-all duopoly, both major parties (Awami League and BNP) resorted to extreme tactics, including nationwide hartals, blockades, or election boycotts, rather than playing the role of a loyal opposition. FPTP also wasted a large portion of votes and fuelled violence and conflict in an already volatile country.

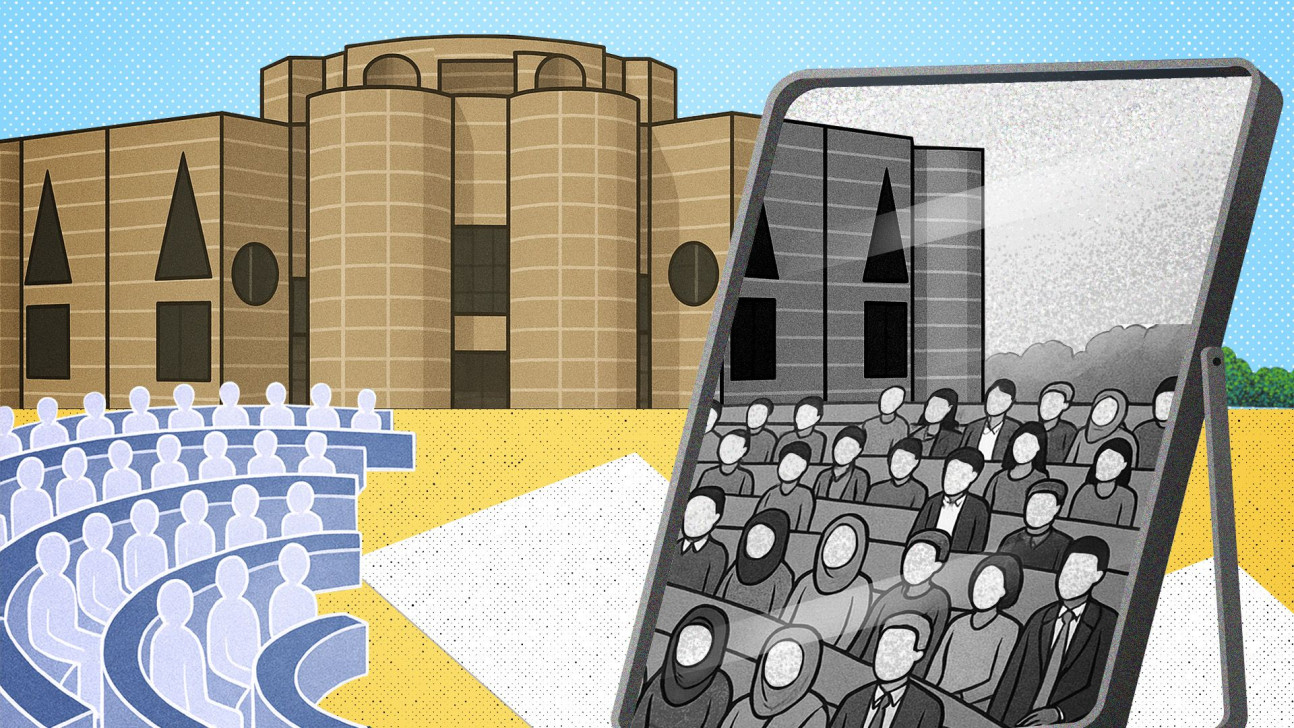

There are legitimate concerns that prevailing political opportunism could also lead to a UH being co-opted by the majority party. Over the past three decades, we witnessed how co-opted civil and police administrations have undermined neutral arbitration mechanisms of the state. Bangladesh's entrenched patron-client system also makes it difficult to hold free and fair elections, especially with the culture of vote-buying on the eve of polling. Moreover, executive encroachment into the judiciary and legislature has repeatedly thwarted prospects for good governance. Parliament has often reflected the executive's will rather than the people's.

The root of Bangladesh's governance issues lies in the ruling party's capture of state apparatuses owing to weak institutions. This, combined with the lack of institutional avenues for parliamentary grievance redress, forces the opposition to take to the streets frequently. Politics has thus become inseparable from violence and turmoil. To shift politics from agitation to legislation and proper governance, the opposition must have real influence within parliament. If they feel the "winner" does, or can, not take it all, incentives for extra-parliamentary confrontation—and the disruptions it brings to citizens' lives—will diminish.

Israel's case is often cited as a cautionary tale for PR in Bangladesh, but its instability stems from design choices that are not being proposed here. Israel's Knesset uses a unicameral, single nationwide district with closed-list PR—features that encourage party fragmentation and fragile coalitions. By contrast, the debate here concerns a bicameral model that retains FPTP for the Lower House and introduces PR only for a limited-power Upper House with a published party list, no role in money bills or no-confidence motions, and at most a time-limited suspensive veto on specified subjects. That architecture seeks inclusion, balanced voter representation, and legislative scrutiny without making governments hostage to micro-parties. Israel's coalition volatility is not an indictment of PR itself; it is a warning to design PR carefully—precisely what a PR UH layered over an FPTP LH aims to achieve.

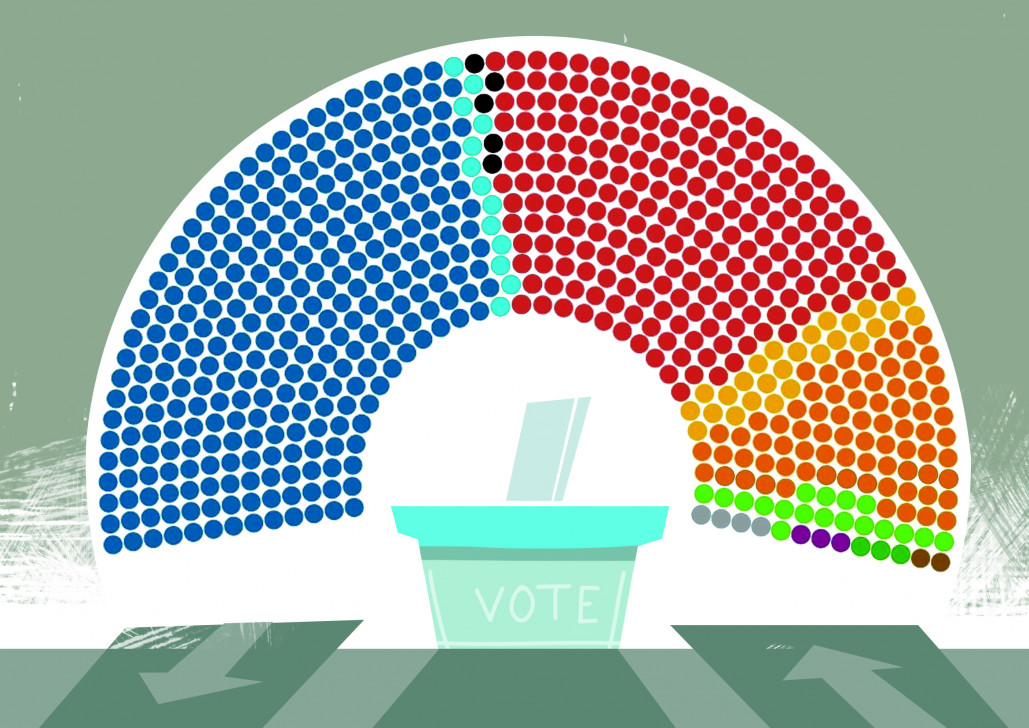

Evaluating counterfactuals, if we use simple arithmetic or the Sainte-Laguë method to project Upper House seats for the 2001 elections, then BNP would have won 44 seats (193 in LH), the AL 43 (62 in LH), Jamaat 5 (17 in LH), and Islami Jatiya Oikya Front 8 (14 in LH)—assuming a 100-seat chamber and a three-percent entry threshold. In this hypothetical scenario, no party holds a majority in the UH. All parties, including BNP and AL, would have UH representation proportionate to their total vote share, putting them on near-equal footing. BNP would likely have partnered with IJOF to pass bills. Either major party would need allies, creating built-in incentives for negotiation. This avenue for democratic cross-party negotiation has been missing for decades. In 2026, this will be more important than ever before, as it marks the first election after a revolution that fought for democracy.

It goes without saying that an electoral system cannot, by itself, transform a country's governance overnight. But it can certainly aid in fostering greater accountability, fairer representation, and political stability. FPTP has historically amplified Bangladesh's governance weaknesses. A mixed system offers a way forward: it maintains government stability (as laws and budgets depend primarily on the LH) while introducing a check through the UH's review role and veto. That said, it is crucial that this is paired with enforceable guardrails that work in tandem, including an independent Election Commission (EC), an empowered Anti-Corruption Commission, and merit-based, transparent civil service recruitment to keep the administration neutral.

The July Charter's move to repeal Article 70 is similarly pivotal, allowing UH members to deliberate without the fear of automatic party expulsion. In this conception, the UH would operate as a serious revising chamber on vital legislation, including those related to constitution, rights, large procurement, and mega infrastructure. When LH majorities reject UH amendments, they should be required to issue reasoned public explanations. To preserve governability and avoid slow policymaking, not every bill should pass through the UH; its mandate must remain narrow and clearly defined. Party lists should also undergo rigorous EC vetting to ensure the chamber leans technocratic rather than patronage-driven.

The priority now is political stability and accountability so that the country has a chance to flourish. A mixed system gives the opposition a tangible stake in lawmaking and reduces the urge to topple governments from the streets. It is vital that the majority party not enjoy total certainty in parliament, for that undermines democracy itself. We must move beyond strawman arguments rejecting PR for the LH when the proposal concerns only the UH. We have already seen what happens when one party monopolises power, and we cannot afford a repeat of that. Bangladesh must dare to reimagine a new political reality that paves the way for true democratic consolidation.

Afia Ibnat is a geopolitical adviser at a Tokyo-based think tank.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments