Will an Upper House solve Bangladesh’s governance woes?

The interim government has been pursuing reforms for balancing the concentration of power focusing on three core pillars of the republic: legislative, executive, and judiciary. Introduction of an Upper House in parliament was initially raised by the Constitution Reform Commission, later by the National Consensus Commission, and finally considered by political parties for the next level of action. Currently, Jamaat-e-Islami and allies demand proportional representation (PR) in both Houses, while the BNP opposes it in both and the National Citizen Party (NCP) wants it only in the Upper House. However, the fundamental issue is whether the Upper House would be able to ensure accountability of the majority party and its leaders and, more importantly, such a House could improve governance practices and judicial independence.

But global evidence on whether these reforms work remains unexplored. The Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) has conducted a quantitative study to unearth this evidence. The study examined parliamentary institutions' impact on governance, accountability, and effectiveness, using data from 108 countries over 25 years.

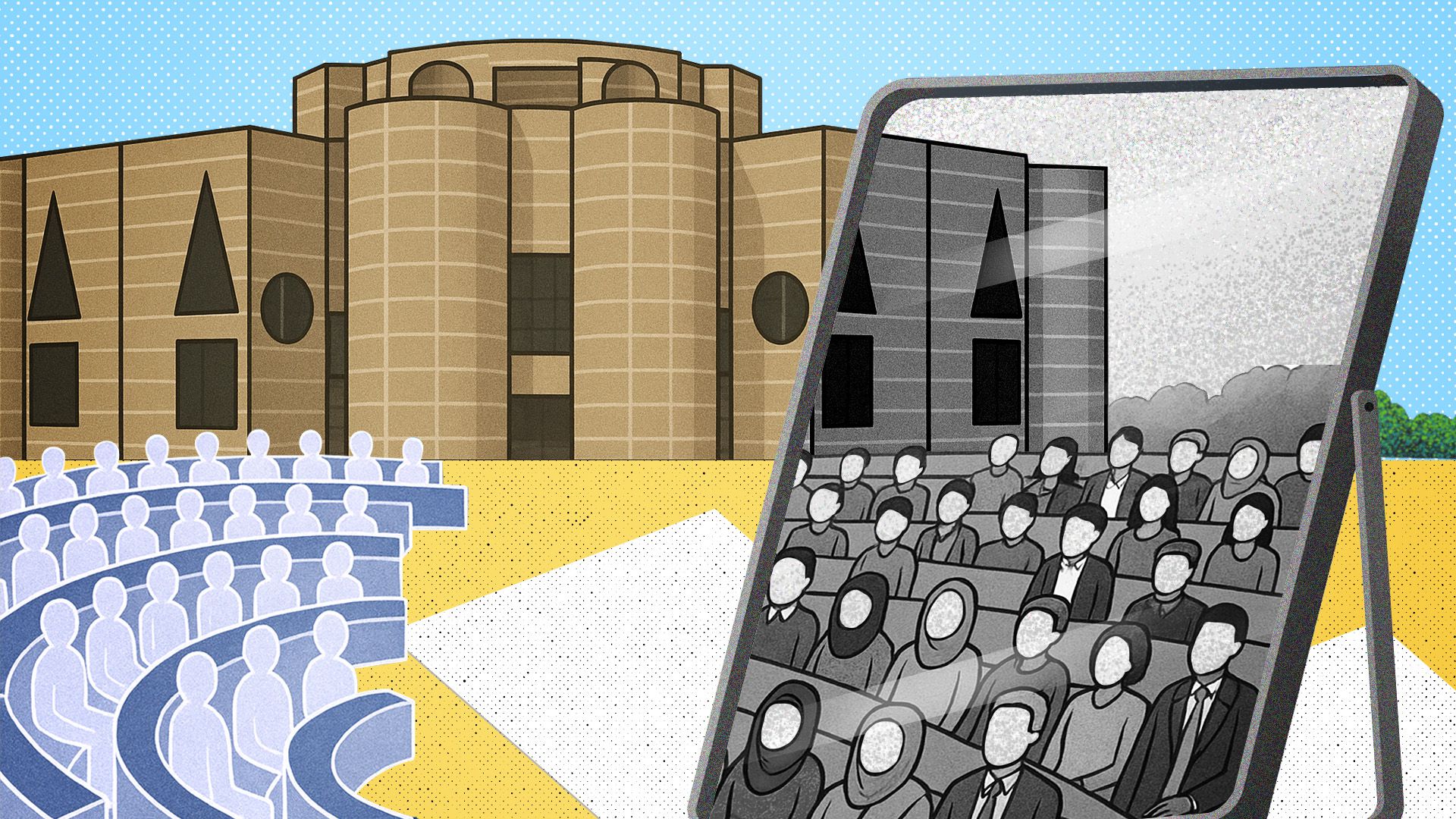

The suitability of any reform depends on the institutional arrangement of a country. And as the current political landscape of Bangladesh stands, these reforms are idealistic at best and chaotic at worst. Governance is a social contract between people and their representatives to carry out their will. The design of the legislative system should have the goal of ensuring accountable and effective representation and governance. To achieve this, the incentive of these representatives must align with this goal.

Weak institutions and clientelist politics have created an elite ruling class serving itself and its patrons. This fundamental lack of quality in governance remains unaddressed in the reform agenda. Simply having more representation with the scope of competition will not ensure quality. In this environment, a bicameral parliament or PR system does nothing to improve the quality of governance.

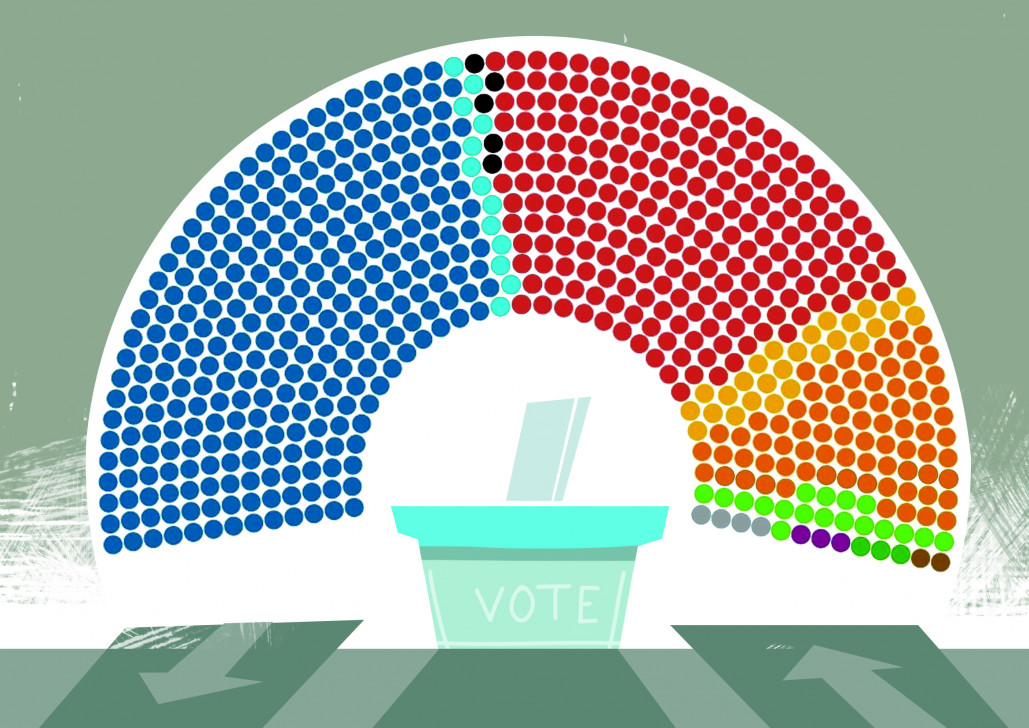

Our study shows the negative effects of bicameralism on several governance outcomes. These include corruption control, effectiveness and accountability as measured in the World Governance Indicators. We also examine social spending and judicial independence. Cross-country regressions show that bicameralism and the PR system generally weaken governance, though bicameralism raises social expenditure. Parliamentary systems improve corruption control and accountability, while military executives show gains in those areas but reduce effectiveness. Alignment between Houses and higher levels of political polarisation are both negatively related to governance indicators. The method of Upper House selection by plurality shows mixed results, with positive associations for corruption control and accountability but negative associations for social expenditure and the judiciary. Finally, a higher GDP per capita (PPP) is negatively associated with government effectiveness and government social expenditure.

Control of corruption

We find that the presence of an Upper House is negatively associated with the control of corruption. Without competition, fair elections, and distinct constituencies, an Upper House cannot ensure scrutiny; its suitability depends on institutional context. In the weak institutional environment of Bangladesh, it only doubles the number of representatives who are susceptible to capture by moneyed interests.

Parliamentary systems better control corruption than presidential or assembly-based ones. Along with this, polarisation in the legislature weakens control over corruption. When both Houses are aligned under one party, scrutiny weakens. Polarisation can become debilitating and make the legislature ineffective.

Single-party dominance makes the Upper House simply a rubber stamp without any incentive to hold the government accountable. This implies the requirement of robust opposition participation in parliamentary procedures and empowerment of standing committees of the legislature. Proportional representation in electoral systems also negatively affects corruption control when adopted in both Houses. Without campaign finance limits, the Upper House risks becoming a lobbying tool to block laws. In political environments dominated by tribalistic voting, simultaneous House elections risk creating legislative supermajorities with very little incentive to provide scrutiny.

Bicameralism and proportional representation are not the panacea to solve all our woes of abuse of power. The fundamental problems of the country's unicameral legislature are getting no attention. Simply increasing centralised systems of power without incentives for participation, resolution and resilient rules-in-use will jeopardise reducing the reform process to just a performative populist exercise.

Governmental effectiveness

Governmental effectiveness is heavily dependent on having clear resolution mechanisms in place for legislatures to move forward despite differences in opinions and having proper participation of the opposition parties in the parliamentary proceedings. Without proper incentive mechanisms for working together and competitive focus on passing legislation, legislatures can be deadlocked or become a rubber stamp in effect. The perception of governmental effectiveness is negatively associated with bicameralism, PR, and high political polarisation. This implies that while PR may offer more diverse representation in the legislature, their ability to work together and convince the people of the government's effectiveness remains in question.

Voice and accountability

The impact on voice and accountability remains positive for parliamentary structures compared to presidential ones. Parliamentary systems show consistently better association with improved governance outcomes compared to presidential systems. Thus, proper accountability must be ensured through due parliamentary oversight rather than leaving it up to the goodwill of an empowered executive branch. The tendency we observed in the previous regime of bureaucratising governance through increasing empowerment of the executive branch ought to be reversed.

The analysis also shows a positive association with the plurality electoral structure of the legislature compared to the PR system. It also shows a negative relationship with bicameralism. This shows that the span and structure of legislative representation do not ensure voice and accountability of the people; rather, it is largely dependent on the institutions and quality of said representation. The mere existence of the Upper House will not guarantee any protection against autocratic tendencies or ineffectiveness.

Government social expenditure

We find that upper houses are positively associated with health and education spending as a share of GDP. The PR system also has a positive effect on social spending. We can infer that the more diverse representation of the population in the legislature provides an incentive to increase allocation in the health and education sectors. This provides some insight into the welfare orientation of bicameral legislative structures.

Judicial independence

The presence of proportional representation in upper houses has shown a positive association with judicial independence. However, this is heavily dependent on the appointment procedure of the judges. In a more diverse and multiparty composition, the legislature may prevent judicial capture if the appointment of judges is conducted through parliamentary vote. Under the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system, the judiciary's independence and role as a co-equal branch of government determining the constitutionality and legality of the policies weakens. Bangladesh has seen first-hand how a subservient judiciary legalised authoritarian tendencies under the previous regime. An independent judiciary is crucial for accountable governance; without it, the legislature cannot limit abuse of power.

Overall, structural reforms are necessary to maintain a participatory and accountable governance structure in Bangladesh. Bicameralism and proportional representation are not the panacea to solve all our woes of abuse of power. The fundamental problems of the country's unicameral legislature are getting no attention. Simply increasing centralised systems of power without incentives for participation, resolution and resilient rules-in-use will jeopardise reducing the reform process to just a performative populist exercise.

Dr Khondaker Golam Moazzem is research director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).

Sami Mohammed is programme associate at CPD.

Views expressed in this article are the authors' own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments