The Spirit of Shaheed Munier Chowdhury

The spirit of Munier Chowdhury has been with me for over 60 years. I first saw and heard him on BTV during his half-hour lectures on books. I used to listen to him spellbound, like everybody else. His mastery over language, his oratorical brilliance, his tone and his humour, his fluency, and even the texture of his voice had literally made him a legend. He was barely forty.

In 1967, when I became a student of Dhaka University, I had occasional glimpses of him zooming past in his Toyota Corolla, or walking along the corridors of the Arts Building with a slight stoop, wearing white khadi panjabi-pyjamas, a tall, magisterial presence. My last sighting of Munier Bhai was right in front of the English Department verandah, walking with his youngest son Tonmoy, only three or four years old at the time.

Not surprisingly, there were stories about him doing the rounds on campus. One such story that I heard from my friends in Mohsin Hall was that Munier Chowdhury was often seen near a restaurant in Nilkhet, opposite the petrol pump, buying paratha and kabab. They assumed that kabab paratha could only be eaten with beer or whisky (we did not know the difference). Munier Chowdhury drinks, they concluded. The story disturbed me. To verify it, I asked Munier Chowdhury's youngest sister—then studying with me in the English Department, the youngest of his thirteen siblings—whether she knew anything about his habits. She assured me that she knew nothing.

Much later, older and more mature, it occurred to me that whether Munier Chowdhury drank beer or whatever was totally irrelevant to his reputation as the finest teacher of the Bangla Department, a great scholar and a public intellectual, a professor much loved and respected by his colleagues.

I had one single encounter with Munier Chowdhury in August or September 1971, and that has remained with me after all these years. After the March 1971 crackdown, Munier Chowdhury moved into his parental home with his wife and two sons (the eldest, Bhashon, had joined the Mukti Bahini). I would occasionally go to Darul Afia, the Central Road house, to meet my class friend Rahela. One day I walked past the front door of the house and noticed a bookcase right under a stairway that went upstairs. I knelt down on the floor, browsing the book titles and waiting for Rahela to come. Munier Bhai saw me (he knew I had come to see his sister), went inside, came back with a mora, saying, "bosho." That single word was all I ever heard from him directly; that single act of kindness has remained with me after all these years, as a confirmation of all the stories of the goodness and kindness of his heart that I heard from his surviving brothers and sisters for more than fifty years.

I had one more indirect, but crucial, interaction with Munier Bhai. In July 1971, when the 7th and 8th papers of our BA Honours were rescheduled after being postponed in December 1970, Rahela and I, along with a couple of friends from other departments, decided to boycott all exams held under the then-occupying Pakistani forces. However, exams were held, results were published, and we were, predictably, at the bottom. Rahela decided to request Munier Bhai to find out our marks for the six papers in which we did appear. As the Dean of the Faculty of Arts—a position he had reluctantly accepted—it was no problem for him at all. He reported that we had both done rather well in the six papers but had received zeros in the ones that we did not attend. A few months later, when Bangladesh was liberated, our results were scrapped and then recalibrated on the basis of the six papers, and we came out on top. Poetic justice, at its best, I thought. Much later, I heard stories that Munier Bhai spoke well of me to others in the family, simply on the basis of my results. That "character certificate" from him paved my way to my subsequent marriage to Rahela.

Munier Chowdhury's love for his siblings, his family, his colleagues, his students, and many others recirculates through endless repetitions. He converted his younger sister Nadera Begum into a communist in the 1950s, and she became a firebrand activist in her own right, going to prison during the language movement; he initiated Ferdousi Majumdar into theatre, much against the conservative values of her parents.

I recently heard from Miti, a journalist and niece of Munier Bhai—who heard it from her mother—that on December 13, 1971, Kushal, Miti's youngest brother, had fallen on the floor and suffered a deep cut. Dilu Apa, Kushal's mother, took him to their Central Road house, where Munier Bhai volunteered to drive them to the hospital. On their way back, he dropped them at their "Pukur Par" house nearby and was repeatedly requested by Dilu Apa to stay back in their house because curfew time was just minutes away. Munier Bhai would not listen. He had to go back home to Central Road, to his family waiting for him.

The next day, the Al-Badr men came for him, and he was never seen again. Dilu Apa never fully forgave herself for not forcing him to stay. He would have been alive if he had stayed with his sister.

On December 14, 1971, there was curfew throughout Dhaka, but euphoria was in the air. We knew that liberation was just round the corner. I called Rahela at noon or a little after. She was crying on the phone and could not talk much. "They have taken Munier Bhai away," she said. I could not fully comprehend what had happened, but I understood that it was something dreadful.

Two days later, when victory was being celebrated throughout the country, a deep sadness had descended on Darul Afia. I went there in the morning and saw people milling around the front yard, talking in hushed whispers, with looks of despair on the faces of those inside. Rusho Bhai, a younger brother of Munier Bhai, was preparing to go to Mirpur with Zahir Raihan and others in search of the missing brothers.

I later heard the full story directly from Rahela, who was present when the abduction occurred. On December 14, around 11.30 in the morning, a group of masked young men came in a jeep, knocked on the door, and asked for Munier Bhai. Rusho Bhai opened the door and regretted the act all his life. The Al-Badr men, pretending to be his students, said they needed to talk to him. Munier Bhai had just taken a shower and was clad in a lungi and genji. They would not let him dress properly, but Munier Bhai hurriedly put on a panjabi as he walked away. Poking a pistol against his back, they pushed him into the jeep. He was never seen again; not a trace of his clothes was ever found. Rahela was standing at the window, looking at Munier Bhai, when he turned back to look at her and told her to move away.

For days following the disappearance of her favourite son Munier, his mother would often look through the window towards the main door, as if waiting for him to come back. He never did. She would simply cry silently; drops of tears would roll down her eyes; she would sigh deeply and say, "Allah. Allah has taken away the best of all my children."

Munier Bhai's siblings, all thirteen of them, were alive at the time of his abduction. For as long as they lived (now only three siblings survive), they told and retold stories about him—stories that they wrote about in newspapers and books, stories handed down to their children, who in turn passed them on to their offspring. It is through these stories that the spirit of Munier Chowdhury stays alive and will live on in the memories of generations to come.

There is a story of Munier Chowdhury's father, Abdul Halim Chowdhury, being accosted at a wedding by a man who asked him, "Are you Munier Chowdhury's father?" He was surprised but secretly pleased and proud. Coming back home, he lamented that now he was known as his son's father. There is no greater pride for a father than to be known for his son's fame.

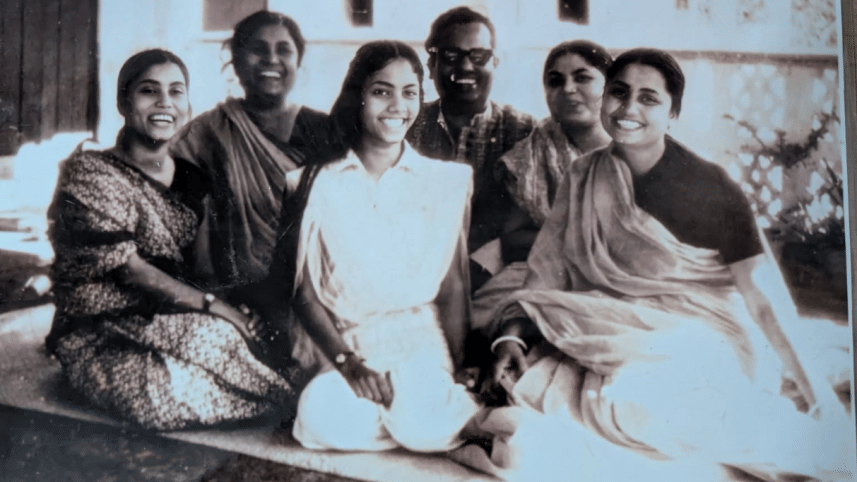

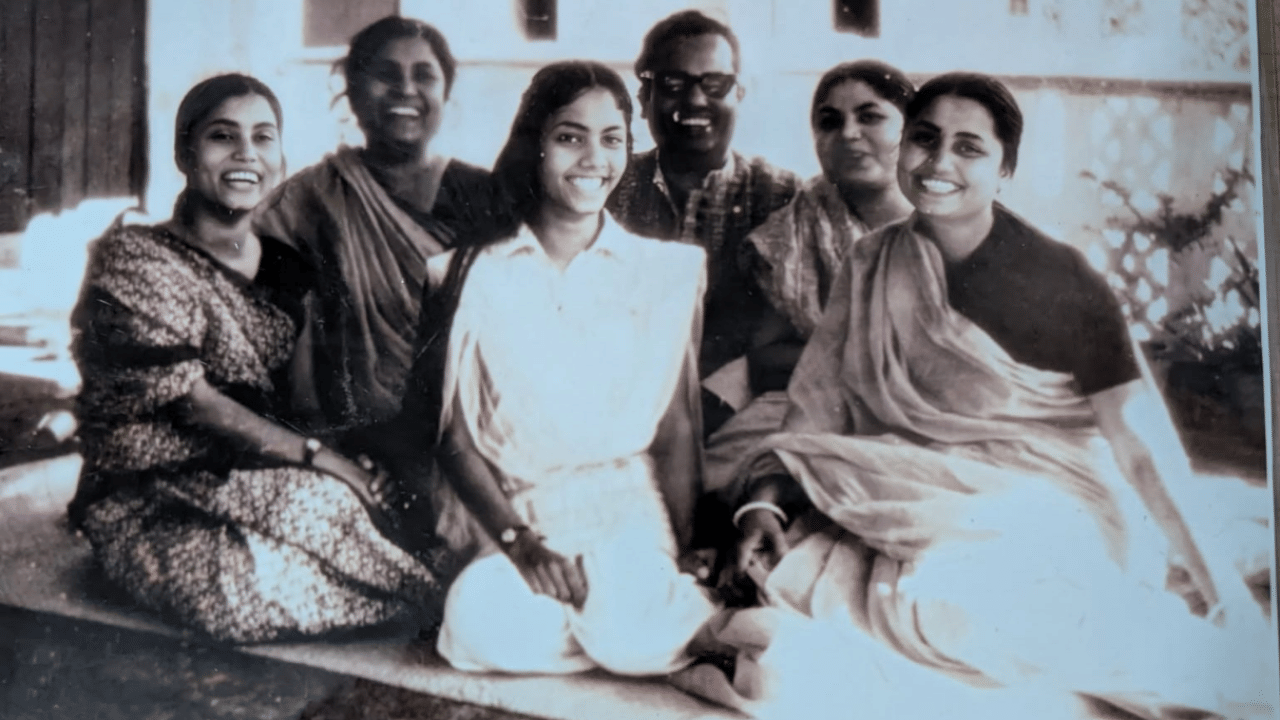

Munier Chowdhury's love for his siblings, his family, his colleagues, his students, and many others recirculates through endless repetitions. He converted his younger sister Nadera Begum into a communist in the 1950s, and she became a firebrand activist in her own right, going to prison during the language movement; he initiated Ferdousi Majumdar into theatre, much against the conservative values of her parents, and she, through her innate talent, achieved stardom as an actress. His siblings, particularly his sisters, were usually the first rapt audience and critics of any new play that he had written. They would sit around him in Darul Afia while he play-acted every single role.

Besides these stories that live on through the memories of his siblings, the Theatre group commemorates his birth anniversary every year more formally and recognises Munier Chowdhury's contribution to drama through a memorial prize in his name. Munier Chowdhury's 100th birth anniversary was celebrated recently on November 27, organised by Theatre. Professor Emeritus Serajul Islam Chowdhury spoke brilliantly about Munier Chowdhury, who was first his teacher and later a colleague at Dhaka University. Serajul Islam Chowdhury was my teacher and later colleague as well. I listened, mesmerised, as my teacher spoke about his teacher. As SIC Sir (that is what we called him), now 89, was leaving, he said to me, "I still miss Munier Bhai." We all miss him. The nation misses him.

Shawkat Hussain was a professor of English at Dhaka University.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments