“In Rokeya’s writing, I see a universal truth”

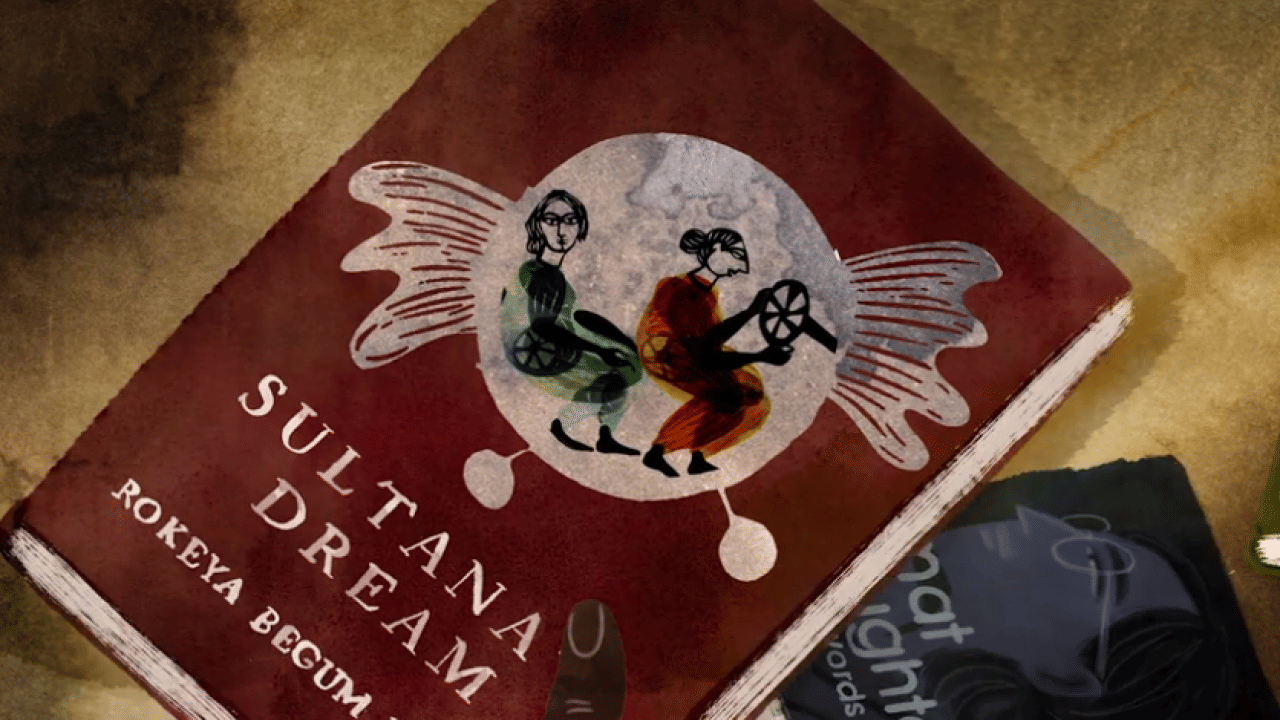

Written in colonial Bengal, Sultana's Dream remains one of Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain's most radical feminist interventions. More than a century on, Spanish visual artist Isabel Herguera brings this visionary utopia to the screen, reintroducing Ladyland to global debates on feminism, power, and imagination.

An experimental animator, filmmaker, and cultural curator, Isabel Herguera uniquely combines art, feminism, and global narratives in her work. Over the past three decades, she has emerged as a leading figure in contemporary animation, earning more than 50 international film awards and gaining recognition for her rejection of commercial conventions and her commitment to animation as a medium that is poetic, political, and deeply human.

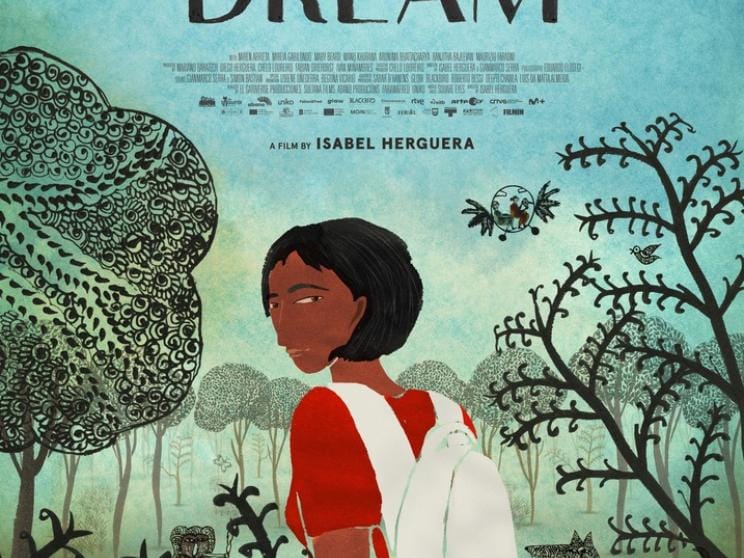

Isabel's film weaves together interconnected narratives: Sultana's surreal journey through Ladyland, insights into Rokeya's life and philosophical struggles, and the introspective quest of a modern woman searching for meaning and belonging.

Her short films, including Spain Loves You and La Gallina Ciega, reflect her interest in subjective experiences and the dynamics of social power, particularly in relation to women. This enduring feminist perspective finds its most ambitious and refined expression in her animated feature film, Sultana's Dream (2023), sometimes referred to as Rokeya's Dream in honour of its literary inspiration.

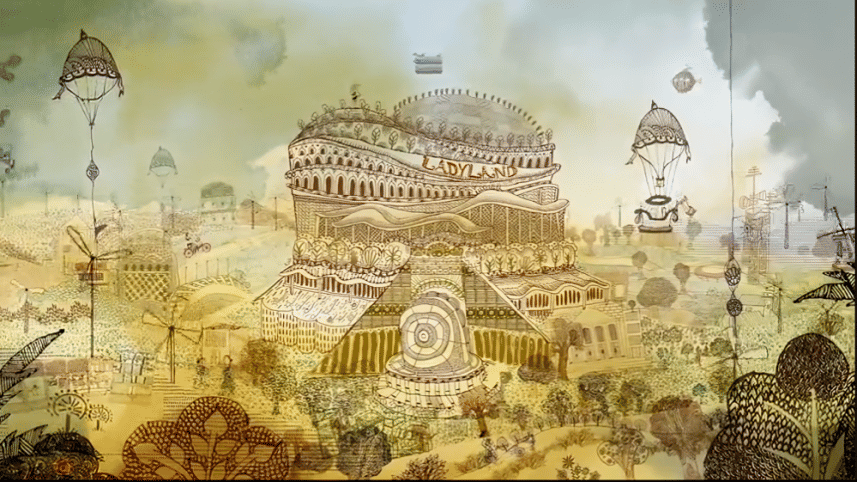

Inspired by Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain's groundbreaking 1905 feminist utopia, Sultana's Dream reinterprets Ladyland—a realm led by women where knowledge prevails over violence and education erodes oppression.

Isabel's film weaves together interconnected narratives: Sultana's surreal journey through Ladyland, insights into Rokeya's life and philosophical struggles, and the introspective quest of a modern woman searching for meaning and belonging.

Visually, Sultana's Dream is rich and textured, blending hand-drawn animation, watercolour imagery, cut-out figures, and motifs inspired by South Asian textiles and mehndi art.

In a global cinema landscape where South Asian women's stories are often overlooked, Isabel's film carries particular weight. By introducing Begum Rokeya's radical vision to international audiences through animation, Sultana's Dream challenges the notion of animation as mere entertainment. Instead, it presents the medium as a powerful tool for political reflection and historical recovery—reminding us that women's dreams are not fantasies, but blueprints for a more just world.

During her recent visit to Bangladesh, I spoke with Herguera about what drew her to Rokeya's work, how she translated its ideas into animation, and why its message continues to resonate across cultures and time. Here is a highlight of our conversation.

Faria Akter (FA): What drew you, as a European filmmaker, to a Bengali feminist utopia written in 1905?

Isabel Herguera (IH): There were similarities between my grandmother and Begum Rokeya. The desire to learn and the desire to know faced obstacles in society at that time. This was my first impression, and I fell in love with Rokeya. Her message is universal; it is not just for Bangladesh. Her message goes beyond borders and remains relevant today.

FA: The film interweaves three narrative strands: your personal journey, Rokeya's biography, and the story of Ladyland. How did you balance these layers without overshadowing the radical imagination of the original text?

IH: I tried to be as honest as possible, and that is why I chose a specific segment where Rokeya talks about the safety of women. It was something I felt was relevant to me, and I believed it was relevant universally. This is what I decided to focus on. The idea repeats across different techniques, but they all move towards one single goal: safety for women.

FA: As a filmmaker, how do you view Rokeya's legacy in the broader history of South Asian women's rights?

IH: In Rokeya's writing, I see a universal truth. I was not born in Bangladesh, and I was not born in India. I do not know the women's situation here as deeply as I know it in my own country. Yet the struggles were remarkably similar from one place to another, and that is what mattered most to me in Rokeya's work.

Faria Akter is a contributor to Slow Reads at The Daily Star.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments