When will there be justice for enforced disappearances?

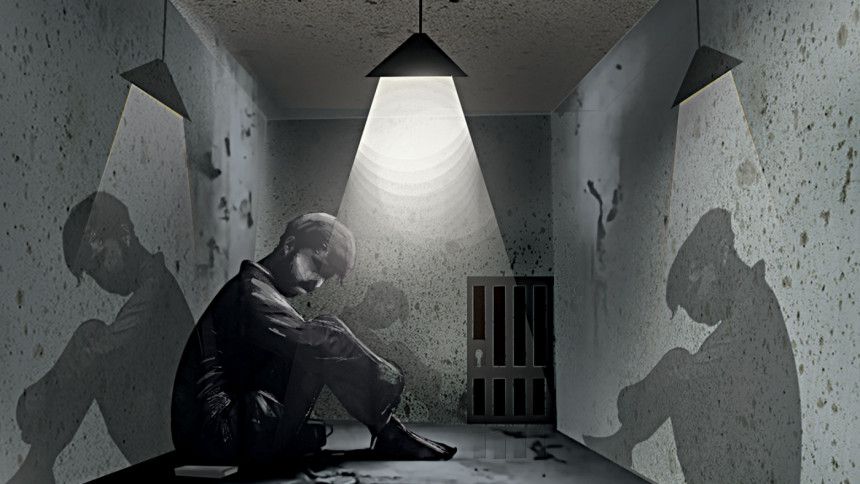

For Sheikh Hasina's Awami League government, enforced disappearance was not just a tool to suppress or remove critics, political opponents, or anyone deemed a threat to them—it also served as a chilling warning to everyone else. During her 15-plus years in power, Bangladesh witnessed this egregious crime on a scale whose full extent is still unknown.

Before my father, Shafiqul Islam Kajol, was disappeared in March 2020, we had heard the term "enforced disappearance" a few times. My mother would sometimes caution him at the dinner table, "You're doing too much; you might disappear." But once that fear became our reality, I witnessed its impact firsthand: even people with no ties to politics, activism or journalism were afraid of criticising the government, even in their own circles, in what should have been their safe spaces. This revealed just how deeply the fear of disappearance penetrated, affecting not only those in politics or human rights advocacy, but also ordinary citizens. How many thoughts were left unspoken? How many voices were muted in the name of survival?

When the interim government came to power last year, it took a few positive steps to address the menace of enforced disappearance. It signed the UN instrument of accession to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances on August 29, 2024, established the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearance, and the chief adviser visited Aynaghar, the secret detention cells where the victims of enforced disappearance used to be confined.

The inquiry commission submitted its second interim report to the chief adviser on June 4 this year. The report mentions that the commission received 1,837 complaints and were able to verify 1,350 of them. It also states the total number of complaints could exceed 3,500. The commission found 16 secret detention centres across the country till the submission of that report.

However, somewhere along the way, progress in this regard stalled. First, it must be acknowledged that dealing with something as sensitive as enforced disappearance was never going to be easy. Preventing state-sponsored human rights violations or holding to account those responsible has frequently proved to be a Herculean challenge. And when we consider that the police and other security and/or intelligence agencies were involved in carrying out enforced disappearances and other such crimes, it is not difficult to understand why progress has been disappointing. Still, the interim government should have made some headway by now.

The first priority should have been confirming the number of victims of enforced disappearance, alive or deceased. It is essential to disclose the full list to the public as a primary measure of accountability. While our justice system has always been slow, the interim government has only itself to blame for failing to accomplish this most basic task.

Second, some form of recognition for the victims should have been established. Many of the families of the disappeared need official documentation to address various legal matters, including those related to banking and property transfer. Such documents should have been issued to the victims' families by now. These families have already endured immense suffering since, in many cases, the victims were the primary breadwinners whose responsibilities or liabilities they have been forced to shoulder alone. An official document confirming disappearance—or, where applicable, a death certificate for those confirmed dead or missing for, say, over seven years—would given these families the legal basis to resolve some of the issues.

Unfortunately, this has not been addressed in the draft Enforced Disappearance Prevention and Redress Ordinance, 2025 either. Perhaps it was not addressed partly because to issue a death certificate, the death would have to be confirmed, for which the time and place of the death (killing) would also need confirmation. While these issues would likely feature in the investigation about the perpetrators, the need for some sort of documentation cannot be disregarded either.

Next, some sort of compensation for the victims should have been introduced by now. These victims were oppressed and persecuted by state agencies that were meant to protect citizens and uphold the rule of law, but instead they participated in this severe violation of human rights. As such, the government should have already implemented a compensation mechanism.

The draft ordinance, it should be mentioned, was approved in principle on Thursday. It is reassuring that under the ordinance, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), and not any law enforcement agency, was made responsible for investigating the cases related to enforced disappearances. But given the limited investigative capacity of the NHRC, which has to rely on the cooperation of state agencies, the provision raises concerns about whether the commission can do its job properly.

We must also talk about the prosecution of those responsible for carrying out enforced disappearances, a process that should have begun long ago. The interim government, formed with the mandate of citizens desperate for justice and truth in the aftermath of the July uprising, had a unique opportunity to pursue these cases free from political bias. More than a year has passed since its formation, with less than six months left before the planned general election in February 2026, and yet the process of holding those responsible to account has not even started. Many of those who committed or benefited from abducting and torturing citizens, denying them their constitutional and basic rights, are still actively working within our law enforcement and intelligence agencies. This is unacceptable. To restore any faith in these institutions, justice must be served without delay.

While the draft ordinance outlines how justice will be pursued in this regard, it also contains some flaws. The minimum punishment upon conviction has been set at ten years' imprisonment. Experience shows that when the minimum punishment for any violent crime is set too high, conviction rates often remain low. For example, in the context of rape, which can carry the death penalty, the conviction rate is below three percent. The draft ordinance also allows for the possibility of capital punishment. To align the law with international standards, this provision must be reconsidered; otherwise, it is unlikely to gain international support. Several human rights bodies have already raised this concern. We need to keep in mind that many of the masterminds behind enforced disappearance have fled the country, and the threat of capital punishment could hinder efforts to bring them back for justice.

Another troubling aspect is the delay in finalising this draft. While the government did just approve the draft in principle, we don't have any possible date for when it will be enacted. With potentially six months left of this government's tenure, legal proceedings, including filing cases and initiating trials, should already have commenced. If not, this transitional period may be wasted, and along with it the hope of expedited actions and impartial investigations possible under a non-political administration. Whether the next government, when elected, will prioritise this issue—and whether it can be expected to act without bias—remains uncertain.

These measures are vital not only for rectifying past mistakes and injustices but also for preventing future violations. So the interim government must address these issues with priority, and justice for enforced disappearances must be served sooner rather than later.

Monorom Polok is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments