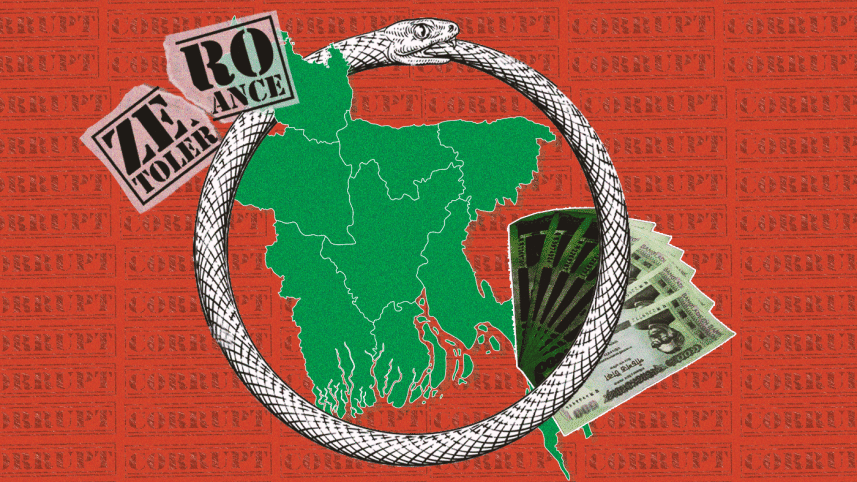

The paradox of whitening black money while fighting corruption

Bangladesh is often described as a "paradox"; it excels in crucial social indicators while scoring poorly on the quality of governance. This paradox was evident when two contrasting news stories emerged from the same session of the Jatiya Sangsad on June 29: one about the prime minister's vow to crack down on graft, and the other about retaining amnesty for possessors of black money. How does one reconcile such contradictions? Has the government redefined corruption by excluding proceeds from illegal transactions, graft, and tax evasion, commonly known as black money?

Critics argue that the definition of black money varies depending on who holds it. This money seems less problematic if the holder is connected to the ruling party. Despite loud proclamations of "zero tolerance," government efforts rarely make a lasting impact on curbing corruption.

Currently, the country is abuzz with complaints about bureaucratic corruption. Previously, there was noise about traders' excessive profits and syndicates. A few years ago, Awami League embodied the zero-tolerance mantra when it tackled illegal wealth from casinos, gambling, and extortion. There was no shortage of theatrics when alleged casino kingpins were arrested in raids, which included quite a few Jubo League leaders, such as Ismail Chowdhury Samrat, Khaled Mahmud Bhuiyan, Kazi Anisur Rahman, and AKM Mominul Haque. Now, however, prosecutors seem to have forgotten about pursuing conviction for the accused, with all of them out on bail.

Considering the slew of unresolved large-scale financial crimes such as fraud and embezzlement of bank loans, insider trading, and manipulations in the stock market involving thousands of crores, one may wonder why there is even talk of a crackdown on corruption.

In the past decade and a half, the stock market has experienced at least three major manipulations. Those who looted investors' wealth faced no significant consequences. Similarly, fraud and embezzlement of bank loans have been long-standing issues. In 2012, the late Finance Minister Abul Maal Abdul Muhith downplayed Hallmark's Tk 4,000-crore fraud, saying, "It is not a big sum." At the time, his words seemed incredible, but now, with the scale of corruption being uncovered, his statement appears less mistaken or humorous. Banks being used to break rules and create precedents for anonymous loans in the billions is now commonplace.

Despite the noise about corruption, the corrupt seem largely unaffected. Government measures, like transfers or demotions after grand corruption allegations, suggest a "hate the sin, not the sinner" approach. Thus, criminals have no trouble withdrawing money or transferring assets before fleeing abroad. Critics of the government or opposition members, however, struggle to secure court permission just to travel.

Everyone wants corrupt bureaucrats tried, but the belief that they will face justice is almost nonexistent. This scepticism arises from the long-standing patronage they receive from political authorities, reflecting a partisan state apparatus. This is evident from the various medals and awards given to administrative and police officials for suppressing political opposition and overseeing one-sided elections. The Suddhachar (integrity) Award, intended as part of the anti-corruption drive, ironically has been bestowed upon record-setting corrupt individuals like former police chief Benazir Ahmed.

The one-sided election on January 7 has probably faded from many of our memories, along with the asset lists of candidates. Since the election was boycotted, and most candidates were from Awami League, the wealth disclosures in their affidavits highlighted how lucrative politics is. Transparency International Bangladesh found that the assets of the top 10 wealthiest MPs multiplied by up to 55 times in five years. The wealth of the richest MP's wife increased about 35 times, and over 15 years, his wealth surged 2,436 times. Many of these politicians are businessmen, yet such business growth is rare even in the West. Transparency's analysis of ministers' and state ministers' wealth also found up to eleven-fold wealth growth and 22 times income growth in five years.

Transparency identified 18 billionaires among candidates. Despite laws limiting single ownership to 100 bighas of land, affidavits revealed many own agricultural and non-agricultural land far exceeding this limit. The top 10 landowners possess 1.5 to 20 times the legal limit.

On January 11, Transparency called for verifying candidates' affidavits, analysing their assets and income statements, and confiscating any illegal asset through proper legal processes. They also recommended seizing land exceeding legal limits, which was not too difficult as these disclosures came in their affidavits. None of this happened. Had politicians' illegal land been confiscated, bureaucrats might have been deterred from pursuing dreams of becoming zamindars.

It has already been proven that raising alarm bells about the corruption of various professionals and groups will achieve little if the political sponsors of corruption are kept out of the reckoning. What's happening now is best described as mega-corruption, and at the rate at which complaints are heard, corruption has become decentralised. Whoever has the power, the maximum of it is being used for corruption. There is no solution to this problem unless there is a change in politics and a return to accountable democracy and the rule of law.

Kamal Ahmed is an independent journalist. His X handle is @ahmedka1

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments