The expressway’s hope of reducing traffic is not lost yet

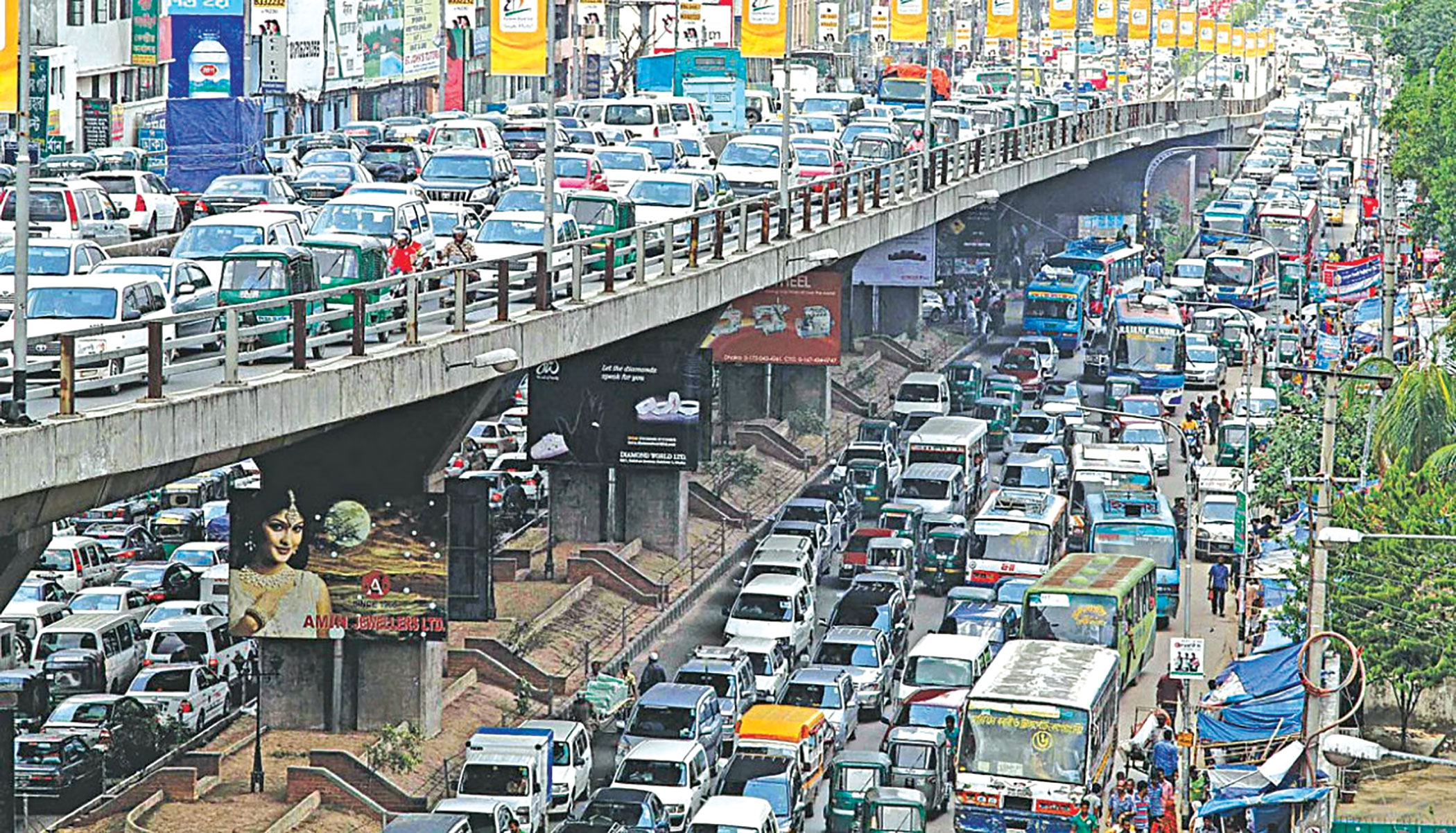

It is well-known that Dhaka faces a shortage of roads and that, while roads are being constructed on top of each other, no new streets are being created. So, the Dhaka Elevated Expressway project included a broadband network of roads, particularly for those travelling long distances in buses and trucks. This project aimed to connect the industrial belt adjacent to Dhaka, facilitating faster and more efficient commutes. Additionally, it aimed to address the complexity of diverting the three bus rapid transit and three mass rapid transit lines also mentioned in the Strategic Transport Plan for Dhaka, reducing the inconvenience caused to the public.

The idea was to utilise railway land without the need for acquisition and to swiftly complete the project in the planned 42-month timeframe, as outlined in the ruling party's then election manifesto. Essentially, if long-distance travellers freed up space on the lower levels of the streets, it was proposed that the public transportation system could be reorganised to complement mass transit effectively. The goal was to establish a transportation skeleton for the entire area surrounding the expressway since vehicles on flyovers could already move quickly, and a similar approach was needed below using a public transport network.

Whether it's the metro rail or an expressway, they all have limitations. But a bus route covers a broader spectrum. It doesn't end where the physically constructed roads or lines do. This is why it is crucial to make public transport faster on the roads. Unfortunately, investors were not enthusiastic about this idea and entered negotiations with the government regarding the placement and routes of the expressway. Investors argued that constructing the expressway outside of Dhaka wouldn't alleviate traffic within the city. This is why we ended up with an expressway within the capital. At the time, rail wasn't a separate ministry from roads. But when the minister realised they wouldn't need to go through the lengthy process of land acquisition since the railway already owned the land, the tender process began as it met all the criteria: speed, location (within Dhaka), and no requirement of land acquisition.

However, reality threw a wrench into this plan. As the project didn't receive the necessary attention from the start, the government decided to separate rail into a different ministry. It injected significant funding and launched projects to improve the railway industry, for valid reasons. However, this clashed with the expressway project, causing further delays. The adverse effect of this was that the expressway's intended purpose – to alleviate traffic while the metro rail was being built – was not achieved. To add to this, traffic congestion worsened even more rapidly, with around a million motorcycles now on Dhaka's streets.

Additionally, the original alignment and ramp location in the tender were not realised either. Whenever there was a hiccup regarding the location, the ramp placement was shifted elsewhere, to Kakoli, Mohakhali, and even on the Bijoy Sarani-Tejgaon Link Road. The last flyover struggles to bear its own traffic load, which has now been exacerbated by the addition of the elevated expressway ramp. This was not part of the original design, signifying how our current model of "development" consists of additions and subtractions.

Constructing a large-scale road like the expressway on top of existing roads naturally comes with drawbacks. To address this, certain design features were implemented, such as the ones at Bijoy Sarani and Kakoli. However, when there is a sudden influx of vehicles in already congested areas like Kakoli, measures like U-loops become necessary. Regrettably, these measures were not implemented, indicating that the completed project significantly deviates from the original.

It is essential to remember that the Dhaka Elevated Expressway is a PPP (public-private partnership) project. In determining tolls, the government plays no role since investors themselves financed the construction and must also maintain operations during the 24-year contract period. The government's role is limited to providing land and viability gap funding. A base rate for the tolls was set in 2013, with adjustments every three years to account for inflation. If currency devaluation reaches, say, 10 percent, that percentage can be added to the current toll. This means that even operators cannot set toll prices arbitrarily, and the government cannot object to price increases within the toll pricing framework.

In terms of pricing, the investors may consider reducing tolls strategically for their benefit. Inside cities, flyovers are utilised primarily when the streets below are highly congested. People are willing to pay for faster travel during such times. However, during late-night hours when there's no traffic, few would be willing to pay tolls. In such instances, the investor could introduce off-peak rates, potentially attracting more users. For daily commuters, paying tolls twice a day is a significant expense. Investors could lower tolls to attract more users, thus achieving a higher return on their investment.

If expressway usage doesn't pick up soon, it could render the project's aim redundant. Such a substantial investment for improved infrastructure should yield visible benefits. The project was supposed to reduce traffic by 30-40 percent – a goal that remains elusive as of yet.

In many countries, traffic engineers work on road transport, bridges, and similar infrastructure to optimise traffic flow. Peak hours result from the uniform application of rules, regulations, and tolls, causing everyone to hit the road at the same time. Encouraging a portion of commuters to start their journeys even half an hour earlier could alleviate congestion. Implementing on-peak and off-peak hour rates can incentivise this behaviour, resulting in smoother, faster travel and financial savings for commuters. Singapore, in particular, takes it a step further with variable congestion pricing, adjusting tolls based on road congestion.

For a Smart Bangladesh, relying solely on fixed tolls is insufficient. By altering travel behaviour and extending the peak hours over a longer period, everyone could enjoy improved lives and the economy could see a boost.

As told to Monorom Polok of The Daily Star.

Dr Md Shamsul Hoque is a professor of civil engineering at Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments