Policing the body, governing the soul

There is no short supply of news of attacks on individuals or institutions in Bangladesh these days. On the surface, these acts of violence are unrelated: shrines vandalised and devotees assaulted; top university officials threatened or manhandled; political vendettas unleashed on touring leaders by their opponents abroad, etc. These disparate episodes are more than brutality or indecency. They signify the rise of a culture of moral policing and coercion that reflects the deeper logic of state and society: the biopolitical control of life itself. And the mercy that we can seek is not from the state, but from the divine providence.

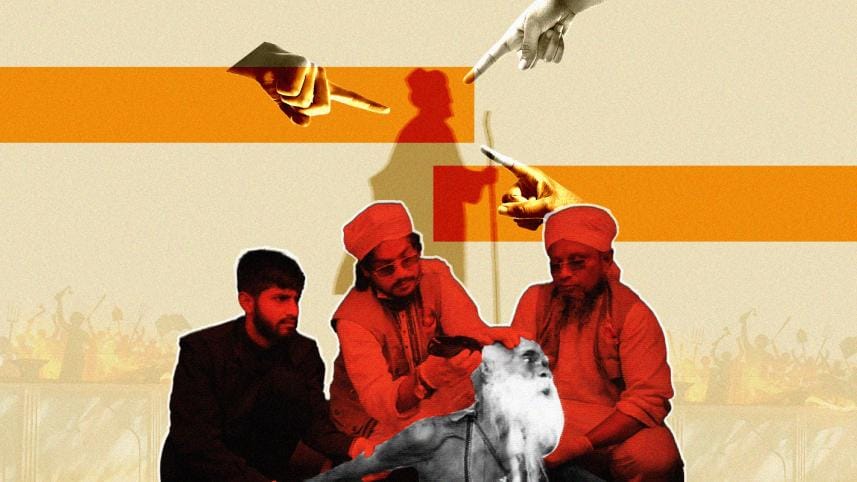

Consider the case of Halim Uddin Akand in Mymensingh. A devotee of Hazrat Shah Jalal (RA) and Hazrat Shah Poran (RA), who retired from the mundane life of being a farmer and dedicated himself to spirituality. For 37 years, he kept his matted hair uncut as a sign of spiritual devotion and minded his own business. There is a video floating on social media that shows the elderly fakir being chased through a market by three men in religious attire. They pinned him down and forcibly shaved his hair. As his locks fell to the ground, Halim cried out, looking at the sky, "Allah, tui dehis!" (Make note of it, Allah).

For a moment, Halim reminded me of all the persecuted prophets labelled as madmen throughout history. He also reminded me of the Welsh bard jumping off the cliff, cursing the king's army who had come to nab him. Halim's prayer is the cry of every hapless oppressed individual to denote an indictment of a society where victims no longer believe earthly justice is possible. The ones who violated Halim's dignity belong to an organised group called "Human Service Bangladesh." They boast their actions as acts of "cleanliness" and "charity." Now why do they suddenly think Bangladesh is rotten and they were born to set it right (to allude to Shakespeare, the Bard)?

Parading violence as virtue was seen earlier this month when the tomb of Nura Pagla was desecrated in Rajbari. The freshly buried body was dug out and set to fire on a highway. Punishing an individual even after death is unheard of in our cultural memory. Should we reflect on the grim history of punishing Republicanism in England, particularly when Cromwell's body was disinterred, hanged, and beheaded, and his severed head displayed on a pole for 20 years? Can death no longer be the final sanctuary where enmities dissolve? Violation of the body, both live and dead, sends a chilling message of intolerance. It tells the larger community that we live in a country that no longer entertain differences, be it spiritual or cultural, even beyond the grave.

Who are the sole agents of morality and culture? How can they function independently of the state system, which includes laws and their enforcing authorities? Groups like Human Service Bangladesh embodies what Foucault called governmentality: citizens turning into vigilantes, policing one another under the guise of moral duty.

Our current head of government took a bunch of political talismans, tied as amulets in his travelling arms, to ward off the political evil spirits that crossed the border with them. In New York, some of the representatives attending the UN General Assembly came under attack by some expatriate groups who ambushed the delegates, including political figures, outside the airport and hurled abusive words and eggs to turn a political demonstration into a physical confrontation. The export of vendetta into the global arena says a lot about our people, and trust me, it isn't positive. It says that we don't have any respect left in us.

That's why I was not surprised to hear that the pro-vice-chancellor of Rajshahi University was manhandled by a mob of students. Factionalism has poisoned our campuses. Earlier, we saw the vice-chancellor of Dhaka University being aggressively threatened by student leaders during a "civil dialogue" on Ducsu. These attacks on the university's top administration imply an assault on the fragile authority of education. Attacks on our top officials leave little protection for other teachers. Already, there have been a number of attacks on teachers in various educational institutions. When these institutions become a battleground for intimidation rather than inquiry, the social contract between knowledge and society collapses. The centre cannot hold; things fall apart. The rough beasts retreat into the centre, echoing a Yeatsian "second coming."

Across all these apparently scattered events, there is one hinge: the disciplining of bodies (i.e. of mystics, politicians, or teachers) is becoming normalised. We become aware of what Michel Foucault called biopolitics. In the olden days, sovereign power reserved the right "to take life or let live." But in modern times, power operates within the capillaries of the social body by regulating, normalising, and disciplining life and death. It polices not only how people behave but also how they appear, how they worship, and how they think. The haircut forced on Halim, the burning of Nura Pagla's corpse, the assault on RU pro-VC, and the attack in New York are far from accidents. They are inscriptions of power onto individual and collective bodies.

The big question is: who is empowered to shore up as a mob or pressure group? Who are the sole agents of morality and culture? How can they function independently of the state system, which includes laws and their enforcing authorities? Groups like Human Service Bangladesh embodies what Foucault called governmentality: citizens turning into vigilantes, policing one another under the guise of moral duty. A Facebook entrepreneur can cut the hair of hundreds of "helpless" people, film it, and monetise it as a "service." Students can attack their teachers and claim they are defending justice. Diaspora activists can ambush leaders abroad and call it accountability. Violence becomes governance, coercion becomes order, and humiliation becomes civic virtue.

But there is another history we must not forget. The land that we have come to call our own was not born from intolerance. Among many things, our cultural identity was shaped by Sufis, Pirs and Bauls, by spiritual leaders, by political activists, and by progressive educators who freed the local people from rigid orthodoxy and taught love as the essence of faith. Shrines were the sites of coexistence, Baul songs were the celebrations of human spirit and depictions of social hypocrisy, teachers were the guardians of enlightenment, and politicians were the chaperons of our democracy. To attack them now is not only a crime against individuals but also an act of self-erasure.

We should be ashamed that a 70-year-old fakir must cry to the heavens for justice. In his cry, we hear a call that highlights our disconnection from the ideals of not only of our Liberation War but also of July, when we sought to make a fresh start.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is professor of English at Dhaka University.

Views expressed in this article are the authors' own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments