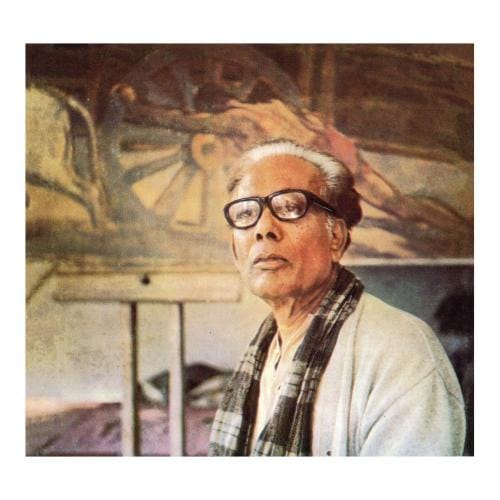

Zainul Abedin, Naib Uddin, and the making of a classic

In the searing midday heat of Baishakh, a farmer is returning home with ripe paddy loaded onto a bullock cart. Rainwater has accumulated in the canal. If the canal can be crossed, home lies safely within reach. On the other side of the canal is the farmers' village. A narrow road runs straight past the village, and the canal runs alongside it. Somehow, the bullock cart manages to cross the canal. But the sheer weight of the paddy load makes it difficult to climb up from the slope. The yoked pair of oxen strain with all their might to reach dry land. Yet the effort feels as arduous as climbing a mountain peak. The cart driver and the owners of the harvest step down into the water. With all the strength in their bodies, they try to push the two wheels upwards. But no matter what they do, the cart refuses to budge. In a secluded village of Mymensingh, this particular moment—of a bullock cart and earth-bound people locked in struggle—was captured by Naib Uddin Ahmed through his compassionate lens.

When the photograph was taken in 1954, famine was still raging in the low-lying deltaic land. The image is said to have deeply impressed Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin. He requested a print of it from Naib Uddin. Later, based on this photograph, he created an artwork with a slightly different composition. He then produced several more works using egg tempera, black ink, and oil paint. Through these media, he introduced varied colours and infused the composition with dynamism through different arrangements. In this way, a real-life scene from timeless Bengal was transformed by the artist's brush into a classic, enduring artwork. The two works by these pioneering figures of photography and fine art acquired a timeless form as narratives of the everyday struggle of ordinary people's lives.

The joint album Bangladesh by Naib Uddin Ahmed and Noazesh Ahmed was published in September 1976. Released from Eastern Regal Industries in Dhaka in English, French, and German, Naib Uddin's black-and-white photograph was printed in the chapter titled 'The People'. The photograph bore the title Man at Work: Pushing a Cart. In later years, Naib Uddin's image became widely known simply as 'Gorur Gari' (Bullock Cart) or 'Chaka' (Wheel). On the other hand, in 1977, the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy published Zainul Abedin [Art of Bangladesh Series: 1], written by Nazrul Islam. Spanning two pages of the book, Zainul's tempera work was reproduced under the title 'The Struggle'. The caption noted that it was painted in 1959 on a 155 by 627 centimetre masonite board using tempera. In his later years, Zainul repainted the image in oil on a 60 by 243 centimetre canvas. In the album Great Masters of Bangladesh: Zainul Abedin, published in 2013 by SKIRA and the Bengal Foundation, this artwork was again reproduced across two pages. The publication notes that the painting was created in 1976.

In addition to the tempera and oil versions, I found yet another version of this image in Zainul Abedin: The Artist and His Works, written by Syed Ali Ahsan and published by the Bangladesh National Museum in 2006. Executed in black ink, the image bears the title Study: Pushing Cart. There is no mention of when this version was created. However, several art critics believe it may have been drawn in the 1970s.

A new phase of discussion around these two works began after the publication of Naeem Mohaiemen's book Banglar Alokchitrer Bastobota Abhijan. Published in December 2024, the book's chapter titled 'Naib Uddin and Zainul's Wheel' revisits an earlier discussion by Munem Wasif, a renowned photographer and teacher at Pathshala—South Asian Media Academy. Showing Zainul's painting of a cart stuck in mud alongside Naib Uddin's photograph, Munem posed a question to viewers: which work came first? Who inspired whom? Did Naib Uddin, after seeing Zainul's painting, go out in search of a similar wheel? Or did Zainul, inspired by Naib Uddin's photograph, sit in his studio and paint the image?

Naeem Mohaiemen, Head of the Photography Department at Columbia University, also presents a number of arguments on the matter. He writes: 'Since there was no practice of recording the dates of artworks, it is difficult to determine which work came first. There exists a small debate regarding the original creation period of Zainul's painting "The Struggle". Complications arise due to different media [egg tempera, oil painting] and titles [The Struggle, Life, Jibon Songram]. Later, Shawon Akand [2009] conducted new research on this issue. By examining a photograph published in a Pakistani newspaper in 1954 and writings by Altaf Gauhar, Nazrul Islam, Syed Azizul Haque, and Nisar Hossain, Akand proposes that the original creation date was 1954. Naib Uddin's photograph was taken before that.'

When the photograph was taken in 1954, famine was still raging in the low-lying deltaic land. The image is said to have deeply impressed Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin. He requested a print of it from Naib Uddin. Later, based on this photograph, he created an artwork with a slightly different composition.

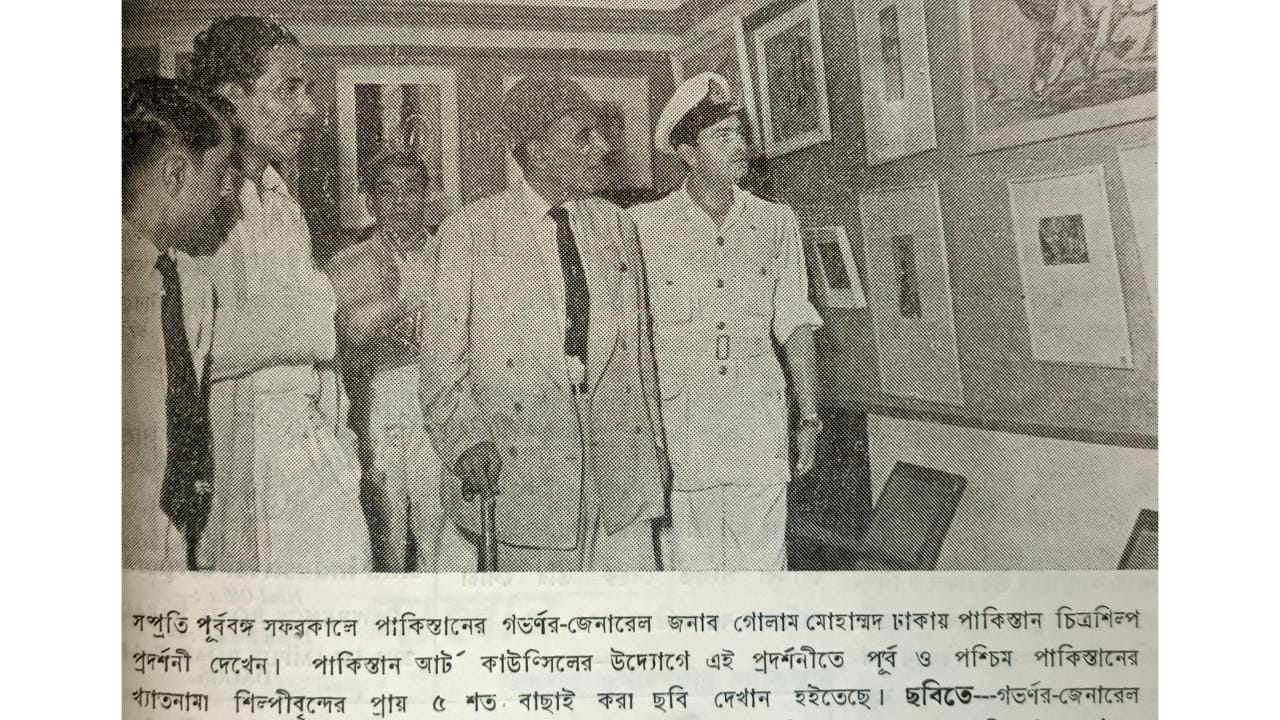

Following the thread of Naeem's writing, I contacted art researcher Shaon Akand. He sent me his article titled 'Some New Thoughts on Zainul's "The Struggle"', published in the July–September 2009 issue of the quarterly journal Shilporup. In support of his claim that Zainul's painting was created in 1954, he cited a review from the monthly Mahe-Nao magazine of that period and a photograph published in the weekly Pakistani Khabar newspaper as strong references. Tracing these references, I went to the Bangladesh National Archives to see them with my own eyes and collected both publications. According to the newspapers, from mid-August to mid-September 1954, a four-week-long exhibition was held at Burdwan House in Dhaka [now Bangla Academy], organised by the Pakistan Art Council, showcasing the finest works of leading artists from both wings of Pakistan. Zainul's bullock cart painting was also exhibited there. However, the displayed work did not carry any title.

In November 1954, a review of this exhibition by Altaf Gauhar was published in the Urdu edition of the magazine Mahe-e-Nau. The article was translated by A. N. F. Ahmed. In February 1955, the Bangla edition of Mahe-Nao published the translated version of Altaf Gauhar's piece under the title 'Dhakay Chitrakala Prodarshani' on pages 33 to 35. On page 35, Gauhar wrote:

"In the central room on the ground floor of the exhibition hall, there was a painting executed on a large canvas. The painting was created by the artist Zainul Abedin. It depicts a bullock cart stuck in mud; the driver is shown gripping the wheel, trying to lift it out of the mire. The image conveys an overwhelming sense of helplessness. It appears that the painter has skilfully attempted to capture every subtle gesture and expression. On one side, a strong and sturdy driver is shown, while on the other side, a powerful pair of oxen are seen straightening their necks and exerting their full strength to raise the cart. To express such emotion in a depiction of living beings is extremely difficult. Many other captivating works by Zainul Abedin also adorned the exhibition. Art connoisseurs who view his newly drawn work titled 'Design' will undoubtedly be mesmerised by its beauty. This artist's future is exceedingly promising. He has never followed the methods of any other artist—and in every subject he has drawn, he has fully revealed both its inherent weaknesses and strengths. Because we spent a great deal of time observing his depiction of the cart driver and the two oxen trapped in mud, we were unable to view his other works."

Showing Zainul's painting of a cart stuck in mud alongside Naib Uddin's photograph, Munem posed a question to viewers: which work came first? Who inspired whom? Did Naib Uddin, after seeing Zainul's painting, go out in search of a similar wheel? Or did Zainul, inspired by Naib Uddin's photograph, sit in his studio and paint the image?

On the other hand, on September 4, 1954, Weekly Pakistani Khabar published a large photograph on page three showing the inauguration ceremony of the exhibition. The photograph shows Pakistan's Governor General Ghulam Mohammad looking at Zainul's bullock cart painting hanging on the wall. Standing beside him are Zainul Abedin, Principal of the Dhaka Art Institute, Khairul Kabir, Secretary of the Pakistan Art Council, and two others. As such, the references from these two newspapers clearly attest that Zainul's painting was created in 1954.

The question now arises—which image was created first? To understand this, it is also necessary to grasp the nature of the relationship between Zainul and Naib Uddin. Those familiar with visual art will undoubtedly be aware of how deeply Zainul influenced Naib Uddin's photography. At the same time, Zainul himself painted works inspired by Naib Uddin's photographs. Their acquaintance dates back to the famine of 1943, widely remembered as the Panchasher Monnontor. At the time, Zainul was a teacher at the Calcutta Art School, while Naib Uddin was an eleventh-grade student at Islamia College. That famine forged a close bond between the two. Zainul would roam the streets of Calcutta, witnessing human suffering and translating those painful realities onto canvas. Naib Uddin accompanied him, photographing the same scenes.

While Zainul Abedin was drawing famine sketches during the famine of '43, I accompanied him through the lanes and streets of Calcutta, photographing scenes of the famine. When I was having famine photographs printed at a studio near Dharamtala crossing beside Islamia College, the renowned photographer Sunil Jana highly praised my work."

Amid the upheavals of Partition, both left Calcutta for Dhaka in July 1947. In 1951, at Zainul's encouragement, Naib Uddin joined the Public Health Department in Dhaka as an artist—a term then used for professional photographers. In 1956, Naib Uddin travelled to Colombo on a scholarship to study social welfare. During this time, he also attended photography courses at the Sri Lankan Art Council, where he became acquainted with the broader dimensions of photographic practice. When he returned home, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was the Prime Minister of East Pakistan and encouraged Naib Uddin to join the PID. After three years, however, Naib Uddin grew disenchanted with photographing official directives of the government or head of state. In 1961, the East Pakistan Agricultural University (now Bangladesh Agricultural University) was established in Mymensingh. Leaving the PID, he joined the university's research division as Chief Photographer. There, he found the freedom to pursue creative photography. The naturally scenic university campus, the Brahmaputra flowing alongside it, its seasonal transformations, the industrious people along the riverbanks, and the Garo Hills and forests all became subjects of devotion for his camera.

Naib Uddin himself documented his relationship with Zainul during his lifetime in his photo album Amar Bangla. In the chapter titled 'The Artist Speaks', Naib Uddin wrote:

"After completing matriculation, I enrolled at Calcutta Islamia College in 1943. During this period, I became acquainted with and developed close relationships with many artists, including Zainul Abedin and Quamrul Hassan. In their company, my artistic sensibility and intellectual engagement with art matured. While Zainul Abedin was drawing famine sketches during the famine of '43, I accompanied him through the lanes and streets of Calcutta, photographing scenes of the famine. When I was having famine photographs printed at a studio near Dharamtala crossing beside Islamia College, the renowned photographer Sunil Jana highly praised my work."

Recalling Mymensingh, Naib Uddin wrote:

"With Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin, on full-moon nights, during monsoon rains, or in autumn amid the enchantment of kash flowers, I spent countless hours on boats upon the blue waters of the Brahmaputra."

I asked Amar Bangla editor Rafiul Islam whether Naib Uddin had ever spoken specifically about this photograph. Rafiul replied:

"Amar Bangla was published in 2009. Before the album's publication, we conducted several interviews with him over time. The recorded video interviews alone amounted to no less than nine to ten hours. Although many years have passed, I clearly remember Naib Uddin stating in those interviews that he had gifted a copy of this photograph to Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin. He also mentioned that the photographs he had taken during the famine of '43 alongside Zainul were lost."

In the foreword to Amar Bangla, the eminent painter Mustafa Monwar wrote:

"Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin's famous painting—the bullock cart stuck in mud with a harvest loaded on top—embodies aspiration. The aspiration of the one carrying that harvest is simple yet profound: I must bring my crop into my own courtyard. That is to say, the harvest is meant to reach the courtyard of the one who carries it—for himself, for a family, for a village, and ultimately for a country. This intense effort and bodily posture that Zainul Abedin painted is mirrored in a similar photograph taken by Naib Uddin Ahmed. Zainul Abedin admired this image so deeply that he requested a print from Naib Uddin. Here, the depth of the relationship between the painter and the photographer becomes evident."

To further understand the stylistic relationship between the works of these two artists, one may turn to another essay by Munem Wasif. Writing in 2012 in the first volume of Kamra, Munem observed:

"We can see the influence of Zainul [Abedin] in Naib Uddin's photographs through their close association. Spinning wheels, ploughs, bullock carts, Santals, rural women—across these subjects, Zainul flows into Naib Uddin, and Naib Uddin flows back into Zainul, again and again. But their relationship is not limited to subject matter alone; it is equally present, in full measure, in matters of form. The same form repeatedly returns in their respective depictions of spinning wheels. Like Zainul, Naib Uddin's photographs exhibit a remarkable simplicity and a sense of restraint. At a time when Europe was racing to capture fleeting moments due to the portability of cameras, Naib Uddin was calmly taking photographs in Bengal, allowing time to unfold. The moments in his photographs are unusually still—almost sculptural."

Another important dimension of Zainul and Naib Uddin's artistic relationship is highlighted by Professor Emeritus and art critic Nazrul Islam. In response to one of my questions, Professor Nazrul said:

"This work, most widely known under the title The Struggle, is considered one of Zainul's finest creations. Inspired by Naib Uddin's photograph, Zainul painted the image. Initially, the painting had no title. When I wrote a book on Zainul in 1977, I myself named the work The Struggle. Naib Uddin's photograph follows a realist approach, while Zainul's painting belongs to an impressionistic tradition. Yet both works are extraordinary. One important detail to notice is that Zainul did not reproduce Naib Uddin's photograph exactly; he painted it in reverse. This altered the perspective and composition of the image. The freedom to break apart and reassemble the mental impression formed by a real image, and to give it a new artistic form, is an additional advantage for a painter. For a photographer, such freedom is more limited."

Placing the painting and the photograph side by side, Professor Nazrul further observed:

"The primary difference between the two images is that in Naib Uddin's bullock cart there is ripe paddy, whereas in Zainul's version he placed an entire tree."

He also pointed out the subtle differences between Zainul's tempera and oil versions of the work, noting:

"In the oil painting, many elements have been simplified. You will notice that in the oil version, the rope tied to the oxen's mouths, necks, and yokes is absent."

After reviewing Naib Uddin's own writings, the discussions of art critics, information from various books, and contemporary journal reviews, my personal understanding is this: the works of Zainul and Naib Uddin were created in the same year. Which came slightly earlier and which followed remains uncertain. It is therefore natural that the question persists—who inspired whom? Let that question remain open.

Shahadat Parvez is a photographer and researcher. The article is translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments