Reading Akhteruzzaman Elias after an uprising

Firdous Azim: There has been an uprising in Bangladesh. There are many who would like to see it as a change of government, with the restoration of order in all sectors as their prime goal. Although it started as an anti-discriminatory movement, the student coordinators who guided the movement envisage a new Bangladesh, a new social order, and now is the time to think of what this phrase means – what an equal, just and fair society looks like.

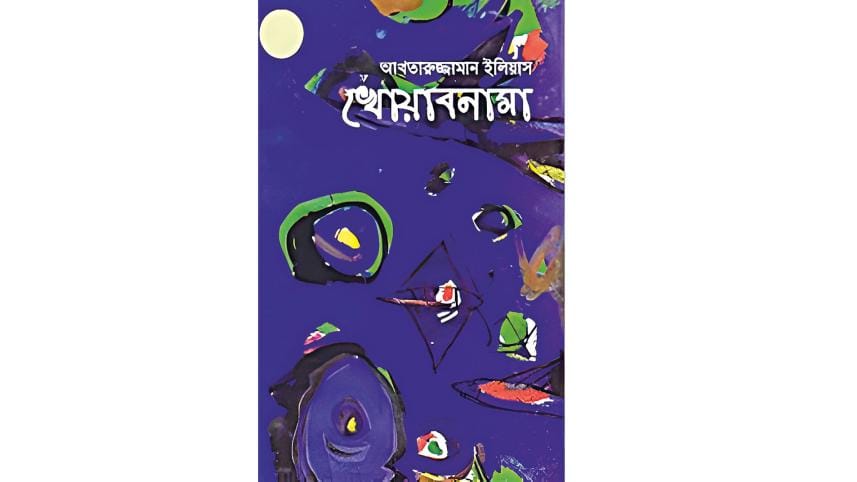

It is only fitting that a special issue of the journal of Inter-Asia Cultural Studies on Akhtaruzzaman Elias's Khwabnama should come out during these turbulent times. This wonderful coincidence connects the past with the present and draws a continuum between accounts of past movements that have shaped us as a nation and polity, to the factors that inspire young people today. This special issue also draws attention to the art – the literature – that such movements can ignite, and that in turn not only acts as an account or representation of revolutionary political fervour, but also as an inspiration for the future.

Khwabnama occupies an interesting, and perhaps an intriguing, place in Elias's oeuvre. The second of what would be a trilogy, in chronological time it weaves its way back from Chilekothar Sepahi, which chronicled the 1969 students' movement to the 1947 Partition of India. Khwabnama thus becomes something of a looking back at the events of 1947 and after. Yet both novels look at founding moments - the first of 1969, the students anticipating the birth of Bangladesh two years later, and the second, looking back at 1947, to allied and mismatched movements, that resulted in the birth of Pakistan, and its impact on its eastern wing. We can only speculate what Elias would have made of this movement in 2024, and how he would have fictionalised the various actors and actions at play within it. We can only hope that a new novel will emerge to complete Elias's trilogy.

The special issue that you will be able to access here delves into the various aspects of Khwabnama, both the hopes and aspirations that independence brings, and the unchanging nature of the backdrop in which these are played out. But the novel that is referred to the most in our present is Chilekothar Sepahi, and the 1969 student movement. It is as though people of a certain generation – themselves likely students of 1969 – see the events of 1969 being repeated in the present. In it, then as now, Dhakaites are shown to be divided and uncertain about what is afoot, with the café debates, the processions, and the unleashing of state violence and ensuing deaths, and the characters such as Haddi Khizir or Osman, which seem to come out of the pages of the novel into real life. There could be a lot written about the differences between then and now, especially as we look out at the nation being conjured in this call for change. It is a different populace that is being called upon at this juncture and a different political terrain in which this call is playing out.

Our readings of Khwabnama, set in a largely rural landscape, gives further historical dimension to the present. The special issue reads the novel to draw attention to the many and divergent ways in which the idea of a new nation plays out. In other words, it reminds that although one may begin as one, the pathways may become different and divergent. Furthermore, despite the radical changes, we are kept in doubt by the novel as to whether these fundamentally change societal hierarchies and relationships. And it raises questions as to what deeper, perhaps more spiritual, even magical visions accompany change.

In our engagement with Elias, many comment on his use of magic realism and his literary style, as the narrative plays on various linguistic registers, and hovers between reality, dreams and magical spheres of being. There is much that a present-day chronicler could learn from this dynamic play with words. Looking at the creative outpouring that the 2024 July movement has brought in its wake – its rappers, its meme creators, its artists – one knows that some time must lapse for a literary expression. At the same time, literature – with a capital L – does not appear to be the creative medium of choice for the young today. A look back at Elias may be timely and inspiring for new writers. For Elias is also a herald of the new. He has, truly, heralded in a new era in Bangla fiction and writing, a way of writing that eschews the social realism that had been inaugurated by the nineteenth century Bangla novel, to draw on hard reality on the ground – landscapes, cityscapes, the grit and grime of everyday living, its smells and excreta – juxtaposing it with its dreams and aspirations, its desires and fears, - to create new forms of literary expression. We hope that the volume we are presenting to you captures some of this, and makes you turn to reading Elias.

Naeem Mohaiemen: Both the novelist Elias and his novel Khwabnama bear witness to the collapse of multiple utopia projects–first, the idea of a just society in rural East Bengal in the colonial period, then the separate peace for Bengali Muslims within Pakistan, the lack of velocity for communist politics within united Pakistan, and finally the implosion of the Socialist parties in post-independence Bangladesh. I locate Akhtaruzzaman Elias' literary work within a terrain of disappointment experienced in Bangladesh at two postcolonial junctures–as East Pakistan after the British partition of 1947 and as Bangladesh after the Liberation War of 1971. In the first instance, post-1947 disappointment was felt by a Bengali Muslim middle class and peasantry that found the new state of Pakistan–comprised of East Pakistan (today's Bangladesh) and West Pakistan (contemporary Pakistan)–to be not the egalitarian Muslim homeland they had imagined. In the second instance, the setback was for those who imagined a socialist future for independent Bangladesh.

To locate Elias' within his context, I look at two other writers–Ahmed Sofa (1943-2001) and Mahmudul Haque (1940-2008) – who had a similar language of angry lament within their work. A group known as the "sixties' writers" were comprised of Akhtaruzzaman Elias, Mahmudul Haque, Ahmed Sofa, Hasan Azizul Huq (1930-2020), and Abdul Mannan Syed (1943-2010). They came out of a Marxist tendency within the literary community, and class conflict dominated their postwar novels. Out of this group, I bracket Elias, Sofa, and Haque as an ideologically aligned trio. Ahmed Sofa was one of the co-founders of the leftist Bangladesh Lekhak Shibir (Writers Camp) –which Elias also joined. Sofa was invested in developing a distinct intellectual genealogy for Bengali Muslims within the idea of Bengal. This Bengal encompasses today's West Bengal in India and the state of Bangladesh– two geographies that were previously together as united Bengal province in the colonial and precolonial eras. Sofa explored a philosophy derived from rural East Bengal and expressed it in a language that pushed against elite Bengali Hindu culture.

Mahmudul Haque was another writer who thought extensively about the reversals seen after Bangladesh's two postcolonial conjunctures. Haque spent his childhood in West Bengal, the half of Bengal province allocated to India in the 1947 partition. Thus, his novels carried an additional melancholia for the loss of a united Bengal where Muslim and Hindu communities once lived together, even if not always amiably. Mahmudul Haque's friendship with Akhtaruzzaman Elias was of two fellow travelers bringing granular observation techniques to the novel.

Novelist Mahmud Rahman has recorded a conversation Haque had with Elias at the old rail gate between Nawabpur and Gulistan in Dhaka. In it, Elias wryly observed, "My territory is from here to the river, yours is on the other side." Elias was commenting on the fact that he was oriented towards regional dialects and geographies, whereas Haque's novels were within a middle-class urban milieu. The two were not always aligned on the role of active political engagement. While Elias joined the left literary circle of Lekhak Shibir, co-founded by Ahmad Sofa, Haque stayed away from the organization. As Rahman recalls from a conversation with Haque, once it became clear that Elias had become an active member of Lekhak Shibir, Haque began to avoid their regular gatherings. "He said he didn't want to be part of any shibir, one with a slogan of stopping the third world war with poetry." (Rahman 2023)

Post-1971 Bangladesh was fertile ground for a literature that could have expressed the passions of left uprising seen in global south countries in the post-1968 moment. Yet Elias took a critical stance toward left politicians' inability to show leadership during the war. The sting of disappointment in this epoch was marked by the feeling that there were no future utopias to be found. The period leading up to 1947 was suffused by the energy of anticolonial uprisings (demanding the end of the British colony) and the call for a separate Muslim homeland (through a separation from India). When that new homeland (Pakistan) failed, East Pakistan, reborn as independent Bangladesh, was a dramatic new emancipatory configuration. After 1971, there were no remaining horizons for national projects of the imagination. Facing a blockage of hope, Elias now focused his analysis on the left political parties, with whom he felt affinity but also castigated for failing to imagine a different future. One aspect of Elias' political engagements in his literary output is the way he expresses outrage in the face of disappointment and its attendant passivity. He does this through the struggles between dueling characters in his fiction. In his short stories, an unstable post-independence is played out among a new petty criminal class, their hapless victims, and principled individuals who, unable to make sense of this new situation, choose madness or collaboration.

I propose that Akhtaruzzaman Elias' literary output was motivated by a personal alignment with the Socialist project and the experience of disappointment in that same politics. There is a corrosive anger that layers his prose, and tragic plot denouements materialize with metronomic frequency. This writing style troubled activist readers, who wanted more clarity of position and denunciation of exploitation. However, I still see his stories as invested in the forward motion of human emancipation from within a framework of socialist politics. I would not go so far as to say these were optimistic works, but neither do they close off the possibility of future collective politics. The experience of devastating setbacks within new political dispensations have been experienced in all the "post" scenarios of the last century–postcolonial, post-revolutionary, and post-socialism. The experience of Pakistan after 1947 and Bangladesh after 1971 has been repeated in other newly independent nations.

Any discussion of Elias must center the fact of his early death and the unfinished third novel. There is a way that this sequence of events leaves us with the option of reading a full arc of redemptive hope within his pessimistic works while missing a crucial unfinished novel–the shape of things yet to come.

Naveeda Khan: In 2011 when I, an anthropologist, started doing fieldwork in the Sirajganj chars I was struck anew by a fact that has been stated repeatedly by the geographer Haroun Er Rashid, that the geography of Bangladesh is amazing. There is a delicateness and diversity to landscapes, flora and fauna but also to the human relations to this geography. So much of music and dance is bound up with this geography, with rains that threaten not to come, the seasonal flowers bursting forth, the smell and sound of wet soil and so on and on. The aesthetic elements that resonate with natural ones are endless. But what is also startling is how quickly all of this devolves to the background, forgotten and soon no more. I am thinking of the crickets I heard all night long or the frogs that crossed my pathway as I snuck out of my house into our garden at night. They are all gone from that garden as clean water and soil, intrinsic to their existence, are no more. I don't remember when I stopped hearing them but when I finally paid attention I was struck by the eeriness of the silence in the garden, interrupted only by the sounds of the city. And what brought my distracted attention back was spending time in the chars. These are strange nodes of space-time on which we have yet to meditate and where the night sounds, really sounds. Sitting in the midst of it you feel yourself become a part of the sounding. This is very much the sense I had when reading and immersing myself in Elias's masterpiece, Khwabnama.

One thing that one misses often in Elias's Khwabnama is his attention to the liveliness of nature. In the novel's opening scene in which Tomijer baap sleepwalks to the Katlahar beel to catch sight of the ghostly visage of the Munshi, stumbles around the beel, lurches one way or the other, we are witness to a daybreak like no other. This is both the scene of a broken man trying to make himself whole and that of nature bursting forth. And just as mention is made of the fates of the characters in the novel even as we are being introduced to them, so we are told of the fates of forests and lakes as these are described to us. Their ends are foretold.

Azim (above) has spoken about Elias' capacity to herald the new through heralding a new literary expression in his two novels, while Mohaiemen (above) has put forward the claim that Elias did not shy away from expressing disappointment while maintaining a commitment to the utopic within his writings. For my part, I claim for Elias's Khwabnama a deep sensitivity to nature and care for ecological issues. This special issue brings together anthropologists, visual artists, literary scholars and political theorists, each engaging the book through their own interests and finding something anew. A visual essay on the work of Syeda Farhana, whose photographic method has an interesting resonance with Elias's interest in excavating the familiar, rounds out the offering. We include here a few photographs taken by her of my char fieldsite which we felt both did justice to the mysterious nature of chars and to the type of riverine landscape that we are asked to imagine within the Khwabnama. We are pleased to have the journal make the special issue open access for a month for our readers. You will find it here.

Firdous Azim (BRAC University) and Naveeda Khan (Johns Hopkins University) are co-editors, and Naeem Mohaiemen (Columbia University) is among the contributors to "Dreams' navel: a special issue on Akhtaruzzaman Elias's Khwabnama", in Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, Volume 25, Issue 4 (2024)

The special issue of journal linked here will be open access for the month of September.

The Taylor & Francis website will keep this special issue open access until end of September: https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/riac20/25/4

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments