Akhteruzzaman Elias’ thought on novel writing in Bengali literature

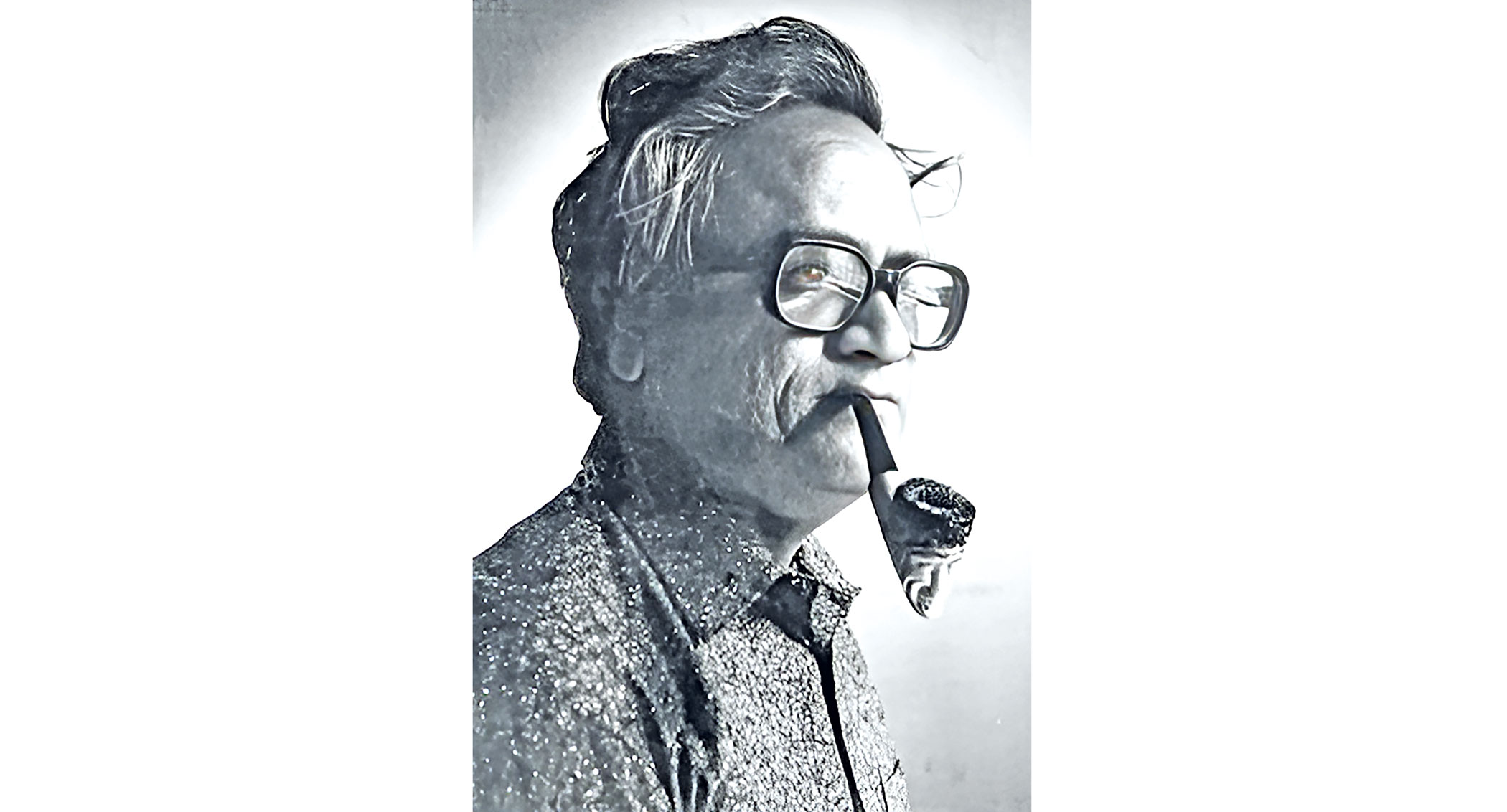

Whenever readers think of Akhteruzzaman Elias (1943-1997), his novels and short stories immediately come to mind. He wrote only two novels—Khoabnama (1996), centred on the Tebhaga Movement, and Chilekothar Sepai (1987), depicting the 1969 Mass Uprising—and both have become timeless classics. He had aspired to write another novel on the events of 1971, but his untimely death from cancer left that dream unfulfilled, marking a profound loss for Bengali literature.

Beyond his novels, Elias was a master of short stories, demonstrating remarkable skill in both forms of prose. His fiction remains a cornerstone of Bengali literature, securing his place as one of its most enduring literary figures.

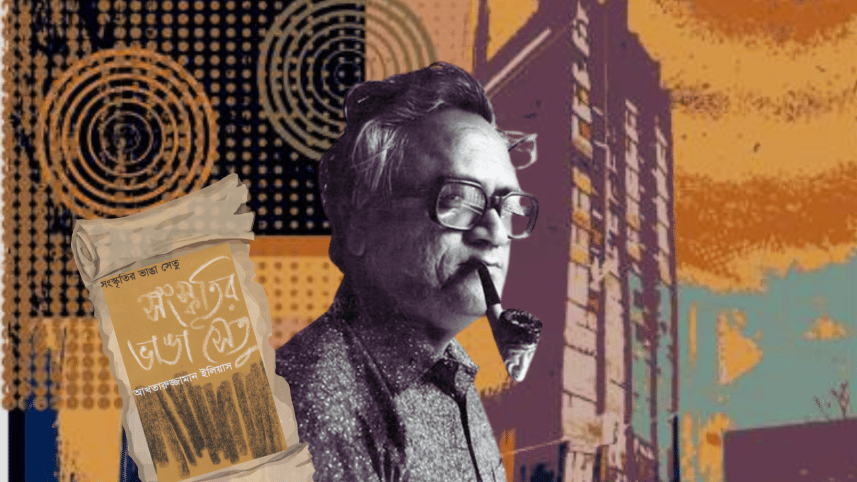

Besides writing stories and novels, Akhteruzzaman Elias would often deconstruct novels as a literary form, emphasising the role of social realism in mastering its craft. He also critically examined modern Bengali novels, highlighting his deep engagement as both a writer and a thinker, which is reflected in his sole essay book, Sangskritir Bhanga Setu (1997), published posthumously.

Elias viewed the novel through a diachronic historical lens, recognising its emergence at a specific moment in history—coinciding with the decline of feudalism and the rise of individualism in modern Europe. While he acknowledged that individualism could be present in poetic forms, he believed it remained implicit, often expressed through emotions like love and hate. In contrast, prose literature, particularly novels, demanded a more structured and mature representation of the individual, who, according to Elias, not only bore greater responsibility but also shouldered a larger share of societal burdens. This need for depth and nuance, he argued, made detailing an essential element of prose writing.

According to him, a poet might be almost a sage—omniscient in knowledge and a perpetual seeker of truth—whereas a prose writer is also a truth seeker but differs in their approach. Prose writers must immerse themselves in the monotony and exhaustion of daily life, yet they strive to uncover its deeper momentum.

Elias observed that, compared to Europe, the emergence of novel writing in Bengali literature was delayed by nearly four centuries, taking shape during the British colonial period through the pioneering efforts of figures like Kali Prasanna Singha, Parichand Mitra, and Dinabandhu Mitra. While constrained by the limitations of the colonial era, these writers remained fully dedicated to their craft and creative consciousness.

What is Elias's view on Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, the author of Durgeshnandini (1865), his first accomplished novel in Bengali? He analyses Bankim's articles Banga Desher Krishak (Conditions of Peasants in Bengal) and Samya (Equality) in Bangadarshan, revealing Bankim's perspective as a true bourgeois in how he observed society and expressed his concerns. However, these concerns are notably absent in his novels. Instead, Bankim crafted characters with historical backgrounds, portraying them with bravery and romantic ideals, yet he failed to capture the socio-political momentum of the colonial era in his literary works.

Elias also ridiculed Bankim's portrayal of female characters, noting that he divided them into two categories: (a) "good" or "very good" women, who are devoted to male figures, and (b) "bad" or "greatly bad" women, who act on their own ideas and emotions. As a result, Bankim largely failed to reflect social reality in his novels—except in Kapalkundala (1866), where he allowed characters and events to develop naturally. In contrast, in his other works, he imposed his own preconceived notions, ultimately weakening their authenticity.

According to Elias, it was Rabindranath Tagore who first allowed for the development of the individual in Bengali prose literature, focusing on life and human development without relying on pre-existing solutions to material and psychological crises. Elias notably identifies Tagore's metaphysical ideas and questions, which are abundant in his poems and music but largely absent in his novels.

The novel emerged after the decline of feudalism, which no longer aligned with the mentality of medieval times. In the context of Bengal, Elias argues that these ideas were first introduced by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, though he did not write a single novel. Dutt embraced secular ideas of the individual and was an iconoclast influenced by European writers such as Mill and Voltaire.

Moving forward, Elias notes that although Sharat Chandra Chattopadhyay directly witnessed the overwhelming reality of village life in colonial Bengal, he portrayed society's shortcomings but failed to fully capture the momentum of social realism, as he himself was a sympathiser of decaying ideologies. Similarly, Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay, while depicting many characters driven by miseries and oppression, worked within a Bengal already in the decline of its feudal colonial system. Though he sympathised with the peasants and the oppressed, he sought solutions to the status quo that ultimately aligned with the political stance of the National Congress.

According to Elias, the colonial period led to the emergence of a paralysed middle class in Bengal, whose decline became increasingly visible by the 1930s and 40s—a reality Manik Bandyopadhyay profoundly depicted in his novels. Elias holds Manik in high regard for his ability to capture social realities, which he considers the core component of a novel. He argues that Manik's Marxist understanding played a crucial role in shaping this perspective. Surprisingly, however, Elias did not comment on Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, whose insights would have been highly valuable.

Apart from the attribute of social realism in the novel, Eliyas opines that one of the core components for writers is the presence of doubt—an essential tool for examining characters and society—rather than adhering to preconceived ideas.

What is Elias's take on Bengali Muslim novelists? He acknowledges that, as latecomers to modern education and social progress compared to the Hindu bhadralok, Bengali Muslims entered the literary scene later. Nevertheless, he notes that they produced remarkable figures who were often trailblazers in their respective fields—Kazi Nazrul Islam in poetry, Abbas Uddin in music, Bulbul Chowdhury in dance, and Zainul Abedin in painting. However, when it came to novel writing, Bengali Muslims had to wait longer to establish a significant presence.

While early writers like Mir Mosharraf Hossain contributed to literature, his works were largely driven by emotion, whether historical, contemporary, or memoir-based, despite containing elements of anti-feudalism. Later novelists such as Kazi Imdadul Huq and Najibur Rahman relied heavily on idealised characters in their works. Elias strongly argues that it was only with the emergence of Syed Waliullah that Bengali Muslim literature saw its first novelist who engaged with modern ideas, incorporating doubt as a central theme—questioning both society and the individual.

This is how Akhteruzzaman Elias traced the entire trajectory of novel writing in Bengal, always considering European literary traditions from his perspective. His analysis is both insightful and thought-provoking, profoundly influencing his own novels, which emphasise social realism, nuance, and doubt—elements that, though few in number, hold significant literary merit.

Priyam Paul is a journalist and researcher.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments