No ceremony can contain Fakir Lalon Shah, yet it is crucial

In the heart of Bengal, where rivers meander like untamed verses and wind hums through fields of ash and mustard, the name Lalon drifts like incense — faint, eternal, ungraspable. On this autumn day, as Kushtia gathers beneath a honeyed October sky to mark the 135th death anniversary of Fakir Lalon Shah, one feels that the unseen bird of his song still flutters between us — restless, undying.

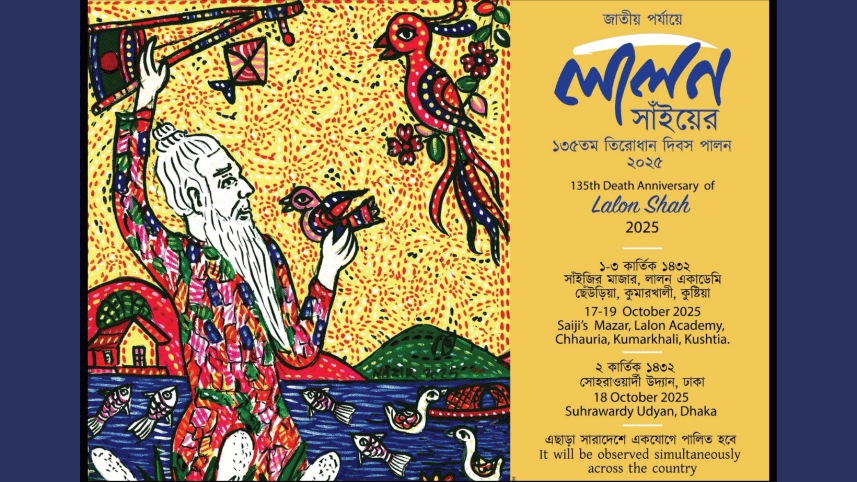

The Ministry of Cultural Affairs has turned this remembrance into a national homage — a three-day festival from October 17 to 19 at Lalon's resting ground in Cheuriya. There will be music, discourse, and a fair that carries the rhythm of his spirit. In Dhaka, too, Suhrawardy Udyan will echo with the same songs on October 18. The celebration begins today at Lalon's Mazar in Kushtia, with the scent of marigolds, the hum of ektaras, and a gathering of minds — among them Professor Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, the eminent scholar who will deliver the keynote address.

The ceremony, presided over by poet Farhad Mazhar, Professor A Al Mamun, and others, will close with a musical soiree in memory of the late Farida Parveen — the voice that once carried Lalon's spirit to the world.

Yet no ceremony, no grand podium, can truly contain the man who lived outside all boundaries. Born in 1774, Lalon's life began like any other, until illness — smallpox — cast him adrift. His companions abandoned him by the Kaliganga River, and there he was found by a Muslim couple, Malam Shah and Matijan.

They nursed him, gave him land, and unknowingly midwifed a spiritual revolution. From that modest akhra in Cheuriya rose one of Bengal's greatest humanists — a man who sang not of heaven, but of the body as its own temple.

"Khachar bhitor achin pakhi, kemone ashe jay," he sang.

Within the cage dwells an unseen bird — coming and going, one knows how.

That bird — the soul, the self — is at the heart of Lalon's philosophy of dehattaya: truth within the body. He dismissed the walls between faiths, urging seekers to look inward, where all gods reside. "Manush chhara khyapa re tui, mul harabi," he warned — O restless one, lose not your root. For man is woven into man as vines entwine the tree.

In his akhra, Hindus and Muslims ate together, women sang alongside men, and all hierarchies dissolved. The ektara and dhol became tools of liberation, their rhythms echoing his dream of a society without caste or creed. His songs, carried orally across generations, speak of human oneness and rebellion against division — a philosophy that found its way into the works of Tagore, Nazrul, and even Allen Ginsberg.

But Lalon's rebellion was also tender. "Milon hobe koto dine, amar moner manusher sone," he wrote — When shall union come, with the one my soul adores? Beneath the mystic's words lies a yearning not just for divine union, but for harmony among humankind.

Today, as the festival lights flicker across Kushtia's fields, and Professor Spivak's words rise under the open sky, one can almost imagine Lalon himself among the crowd — barefoot, smiling, the unseen bird fluttering on his shoulder. The ektara hums softly in the dusk, and his voice seems to return once more:

"Dhonno dhonno boli tare, bendhechhe emon ghor…"

Blessed is he who built such a house upon the void, where a mad one sits — alone with the One.

In a world still divided by faith and flag, perhaps this madman of Kushtia was the sanest of us all — still teaching, even now, that the divine begins where humanity does.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments