Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan: A chance encounter, and the rest is history

I: THE BACKGROUND

Pierre-Alain Baud was at Theatre de la Ville in Paris by chance. He had just finished listening to a concert by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Party. Like many other foreign ears, before and since, he was mesmerised. He may not have understood the words, but the power of Nusrat's voice left a mark in his heart that evening.

Serendipity had it, Pierre would meet Nusrat the next day at a railway station. From then, the two became friends. Pierre accompanied Nusrat in many of his concerts around the world.

In 2008, Pierre decided to pen his experience as a memoire in the French, Le Messager Du Qawwali (Éditions Demi-Lune, 2008). The book is the first on Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan through western eyes, as the author humbly mentions in the preface.

An Urdu translation, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan: Qawali Ka Payam Rasan (Sang-e-Meel Publications, 2014) translated by Shaukat Niazi followed in 2014. A second translation followed in 2015—Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan: The Voice of Faith (HarperCollins India), by Renuka George.

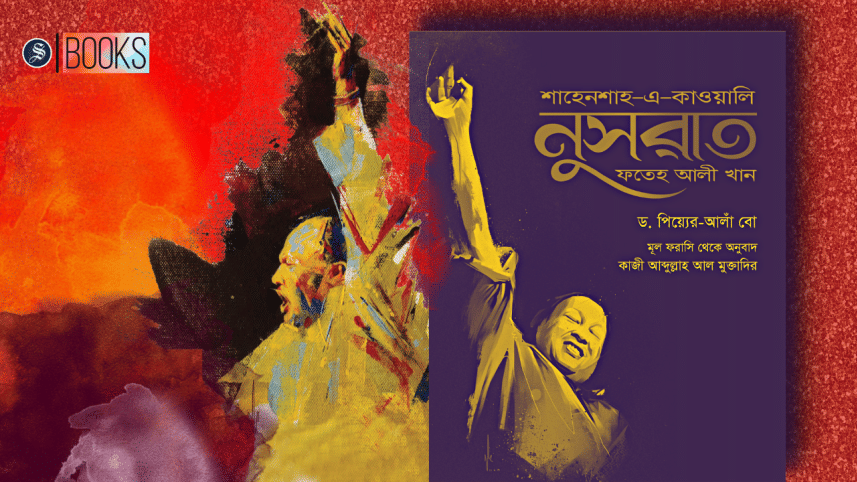

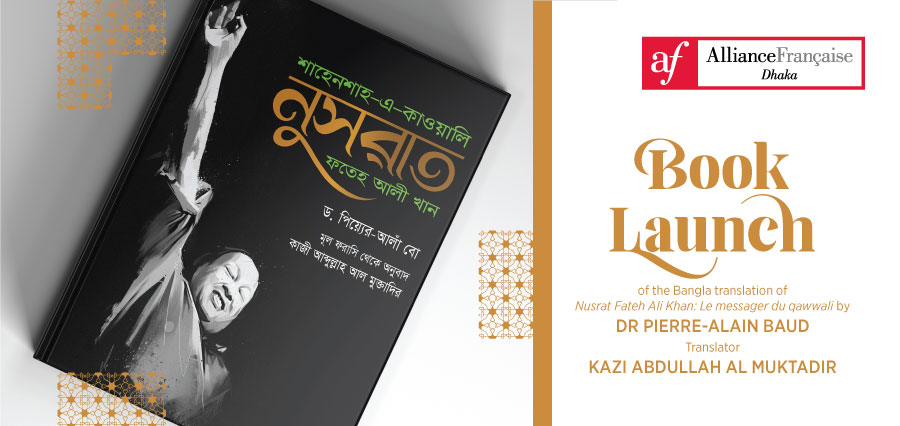

Pierre Alain Baud's book has now been translated into Bangla from the original French, Shahenshah-e-Qawwali: Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, by Kazi Abdullah Al Muktadir. It was published by Pathak Shamabesh, with support from BEXIMCO in September 2022.

II: THE BOOK

The organisation of chapters in the book is very well done. After a preface and after narrating their first meeting, Baud traces the historical roots of Qawwali in South Asia with emphasis on the Chisti Order. He narrates the religious and secular branches of Qawwali and delves into how it became synonymous with the identity of Pakistan soon after the 1947 partition.

The next chapter details Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan's lineage over a few centuries. However, the main emphasis is on Nusrat's father, Fateh Ali Khan Sr, who was the leader of the family Qawwali Party before and after the 1947 partition. In this chapter we see how the Khans separated themselves from other Qawwali parties through classical music and by improvising in tunes and singing in the local tongue (Punjabi).

Nusrat's father never wanted his son to become a Qawwal. In the next two chapters, little anecdotes of the seen and the unseen dimensions of Sufi spiritualism describe why and how Fateh Ali Khan Sr's dream did not materialise. Here we see the rise of Nusrat as a national icon in his country.

Nusrat's journey outside South Asia and the South Asian diaspora starts in 1985 with the WOMAD festival in the UK where he met the label founder Peter Gabriel. Then came France, Tunisia, Brazil, Japan, and South Africa.

But this chapter has one gap. It makes no mention of Oriental Star Agency and Nusrat's association with Mohammed Ayub. It was Ayub who introduced Nusrat to the Punjabi and Pakistani diaspora in Birmingham, which later opened other avenues that the book discusses nicely.

The next chapter narrates Nusrat's improvisation of Qawwali with different genres and the film industries in Hollywood and Bollywood. The final chapter narrates the final days of Nusrat's short life and the legacy he left.

III: THE TRANSLATION

Kazi Abdullah Al Muktadir grew up in a village in Thakurgaon. His father once brought two cassettes of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan from Dhaka. They were a collection of 'filmi' songs. Muktadir fell in love with the voice like Pierre did some years before.

Serendipity worked for a second time. Muktadir joined Alliance Française de Dhaka as a programme officer. Soon he met Pierre. Pierre gave Muktadir the French book and asked if he would translate it into Bangla. That was it, although the project took years to see light.

The book will fill an emptiness Bangla speaking people have on Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. The translation reads smoothly. The book is by no means encyclopaedic, with only 130 pages of text. It nevertheless provides a good primer to Nusrat's life as a musician and the legacy he left. If a review is to be taken with a 'pinch of salt' then the price of the book is a bit high.

The book will never replace the experience of the voice of Nusrat, but it will provide anecdotes to why that voice was so special.

Asrar Chowdhury is a Professor of Economics at Jahangirnagar University and the author of Echoes, the fortnightly column in SHOUT magazine. Email: asrarul@juniv.edu.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments