Cashless society still a distant dream

In June, Sanzid Imran, a Dhaka-based software engineer, boarded a Dhaka-bound bus from Cox's Bazar after spending the last of his cash on a hotel checkout. It wasn't a reckless move. "I figured I could always get some cash if I needed it," he said, recalling the memory. In Dhaka, a cashless life was not just possible, but normal.

But when the bus pulled into a service station near Chattogram for its scheduled break, Sanzid descended, stomach grumbling, and scanned the rows of stalls for snacks—and for a place to pay. No ATM in sight. No bKash or Nagad agents. No QR code stickers. Just cash-only vendors, operating in the quiet comfort of Bangladesh's informal economy.

"That's when it hit me," he said later. "We keep talking about digital Bangladesh. But sometimes, one snack shop in the middle of nowhere can break that illusion."

That illusion, as it turns out, is shared by millions. While Bangladesh has invested heavily in building the infrastructure for a cashless future, the journey has been anything but smooth. The central bank has launched platforms, set targets, and drafted visions. But in the humid stalls of rural markets and even the street corners of Dhaka, cash still clings to life, not just as a habit, but as a necessity.

In 2023, the Bangladesh Bank declared that 75 percent of all transactions would be digital by 2027. It was an ambitious goal, echoing India's success with its Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and China's overwhelming dominance by Alipay and WeChat Pay. Even Bhutan and Nepal, countries with far smaller economies, have made quiet strides toward digitisation.

But in Bangladesh, the road is bumpy, potholed by poor infrastructure, patchy internet, reluctant banks, user mistrust, and a lack of incentives. With less than a year and a half to go, the central bank's goal appears increasingly out of reach.

The flagship initiatives—Binimoy, Bangla QR, and TakaPay—were meant to be the scaffolding of a digital revolution. Instead, they stand as cautionary tales.

Binimoy, launched in November 2022 at a cost of Tk 65 crore, aimed to emulate India's UPI—a platform to enable seamless, interoperable transactions between MFS providers and banks. Developed by the Innovation Design and Entrepreneurship Academy Project under the ICT Division, it was, on paper, an elegant solution. In practice, it failed to gain traction.

"Binimoy failed due to poor user experience, lack of promotion, and banks' unwillingness to integrate," said one senior BB official. After the political changeover in August 2024, the project was suspended indefinitely.

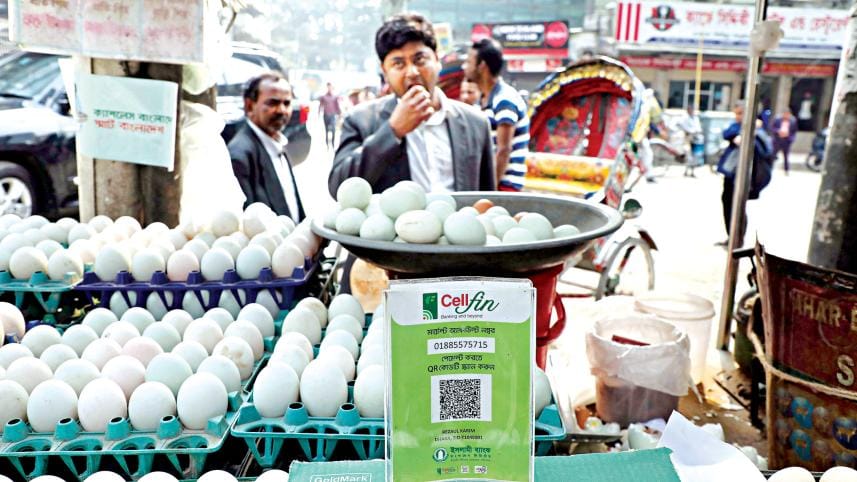

Bangla QR, introduced in January 2023, sought to standardise QR code payments across all platforms and banks. But two years later, it's still absent from most storefronts. "Many banks don't even have the digital infrastructure—like updated mobile apps—to support Bangla QR," said a central bank official. Instead, stickers of mobile financial service providers like bKash and Nagad dominate, and the unified system struggles to find a foothold.

And then there's TakaPay, a local currency debit card launched in late 2023 to reduce dependency on global payment networks like Visa and Mastercard. Despite being the first of its kind, only eight banks offer it. Most consumers haven't even heard of it.

Speaking to The Daily Star, BB Executive Director Areif Hussain Khan acknowledged these shortcomings. "We observed that cashless initiatives have stalled due to various reasons," he said. To counter this, the central bank now plans to mandate Bangla QR adoption by all banks within six months.

Additionally, the central bank is working with US-based tech firm Mojaloop—backed by the Gates Foundation—on a new interoperable digital platform to replace Binimoy.

Khan also pointed out the need for greater public awareness and mentioned plans to hold seminars to promote cashless adoption.

Experts say cash remains dominant in Bangladesh because it offers invisibility. For small business owners, street vendors, and even mid-sized retailers, cash transactions come with fewer strings attached—no VAT, no tax trail, no surveillance. Digital payments, by contrast, leave footprints that invite scrutiny.

"If a transaction takes place through a bank, then VAT and tax matters become accountable or traceable. But if the transaction is done in cash, then VAT and tax can be avoided," says Mohammad Ali, managing director of Pubali Bank.

"So, there is no incentive, and on top of that, digital transactions bring VAT and tax implications," he said.

Managing a cash-heavy economy is also very costly. The process of printing, handling, transporting, and storing currency notes and coins imposes a significant financial burden on the central bank and financial institutions alike. Businesses also incur costs in cash handling, counting, reconciling, and depositing.

Bangladesh Bank's spokesperson Hossain reiterated that transitioning to a cashless society remains a top priority under the leadership of the current governor. "Bangladesh spends crores of taka each year just to manage cash. We have no alternative but to move forward," he said.

Ali echoed the same sentiment. "Managing cash is very expensive for banks, which is why increasing cashless transactions is essential to reduce the operational cost of a bank."

He estimates that a single Bangladeshi bank spends as much as Tk 260 crore each year just to manage cash—printing, transporting, securing, and storing it.

He also points out that there are no incentives like tax rebates or cashback offers to drive customers toward digital transactions.

"Another issue is that MFS providers have already onboarded most of the retail shops. From QR codes to everything else — the MFS companies have brought them under their umbrella."

Banks see that if they try to penetrate this space, it still ends up benefiting MFS providers more, given their mandate, he said, adding that they (MFS providers) have become more proactive in this regard.

MFS providers are also doing much more marketing at small retail stores compared to banks. "That's why banks are lagging behind, particularly in terms of QR code adoption."

Stuck in Transition

Thirteen MFS providers operate in Bangladesh. Among them, only four—bKash, Nagad, Rocket, and Upay—hold a meaningful market share. In May 2025, MFS cash-out transactions reached a record Tk 44,355 crore, up from Tk 38,327 crore the previous month, according to BB data.

In comparison, merchant payments through MFS stood at Tk 7,433 crore, government-to-person (G2P) transactions totalled Tk 655 crore, and utility bill payments reached Tk 3,372 crore.

MFS platforms now offer services such as savings, peer-to-peer transfers, bill payments, merchant payments, mobile recharges, and G2P disbursements, reducing dependence on physical cash.

However, industry insiders said that while merchant payments and G2P transfers are rising, most users still use these platforms as glorified cash-out mechanisms.

Rural and marginalised communities often lack the digital literacy or infrastructure to engage in anything but basic transfers. The irony is that the very populations that digital finance could empower are also the ones least able to access it.

"My son regularly sends me money through bKash. But I do not know how to shop through bKash. I am a poor person. I cannot afford to lose money. So, I cash out all the money," said Jharna Parvin, 60, a resident of Gazipur Sadar.

bKash's head of corporate communications, Shamsuddin Haider Dalim, says they're working to change that. "We're training small merchants, rolling out new features, and trying to shift users away from just cash-out habits," he said. But the scale of the challenge remains immense.

Experts said MFS providers can play a more transformative role by improving interoperability, expanding merchant networks, reducing transaction costs, offering incentives, and collaborating with the e-commerce and transport sectors.

Bankers and industry players added that, alongside MFS, internet banking, agent banking, and digital wallets are contributing to building a cashless society, but overall progress remains slow.

Pubali Bank's Ali believes the transition won't happen through policy papers—it will require legislation and enforcement.

"For example, in India, a business can't renew its trade license unless it has a digital payment option. During the renewal, if they have a bank account, then they must have at least one digital terminal, like a QR code," he explained.

"If QR codes are made mandatory, they will be displayed. And if the QR code is displayed, customers who want to pay digitally using QR codes will be able to do so," Ali added. "If this is incorporated into our trade license system and all municipalities and upazilas implement it, then all shops will be forced to display their QR code."

The Pubali Bank managing director said this is the most crucial step, and if it isn't done legally, then "no matter how much we try to convince people, it won't work".

Citing another example, he said, "We have PI banking, and even my own officers weren't using it. Many of them. Then I told them that if they do not activate it within a month, their salary will be withheld. Now everyone has done it."

He also advocates for other restrictions, such as capping large cash deposits, limiting withdrawals, and forcing retail spaces to adopt digital terminals. The goal isn't just to nudge people toward digital—it's to make cash inconvenient.

"When you launch a new product, at first you need to be courteous and supportive to gain adoption," he said, adding that "once the product matures, then enforcement becomes necessary."

"If this goes under enforcement, then the cashless society goal will be achieved faster."

Calling for restricting one-time cash withdrawal and deposit limits, he said, "There are people who bring crores of taka in cash, bags full of Tk 1 crore, to the market. If the deposit limit is capped at Tk 10 lakh, they will be forced to think: what's the alternative?"

"Especially wholesale traders, back-office dealers, distributors — they'll think: I collect Tk 1 crore daily, and now I'll only be able to deposit Tk 10 lakh? So, should I start running around to four or five banks daily?" These complications will push them toward QR codes or other digital payment options, he pointed out.

Until then, people like Sanzid Imran will continue to live in a halfway world—digital in theory, but analogue when it matters most.

His story isn't rare. It's Bangladesh's story: a nation with the ambition to leap, but shackled by the very systems it hopes to transcend.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments