Inflation outpaces wage growth for 44th month

For nearly four years, prices in Bangladesh have been rising faster than people's pay. Every month, workers earned a little more on paper, but that extra money did not stretch as far in the market. Now, for the past two months, even the pace of income growth has started to slow, making an already difficult situation even worse for low- and middle-income families.

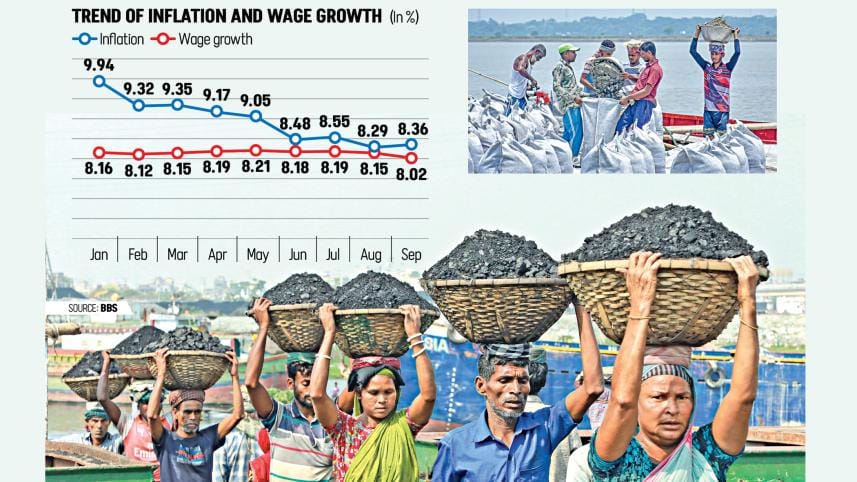

Latest data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) show that wages grew by 8.02 percent in September, down from 8.15 percent in August and 8.19 percent in July. Inflation in these months stood at 8.36 percent, 8.29 percent, and 8.55 percent, respectively. This means workers' real earnings—the amount their wages can actually buy—have continued to erode.

Economists say this steady erosion of real income is weakening household purchasing power and pushing many families closer to the edge. So, while a worker might earn Tk 10,000 today compared to Tk 9,000 a year ago, if food, rent, and transport costs have risen even faster, that worker is effectively poorer. This has been a constant trend since early 2022.

"Workers are under pressure from both sides: prices are rising while wage growth is losing momentum," said Zahid Hussain, former lead economist at the World Bank's Dhaka office. "It's like getting struck twice—once on the head and again on the feet."

He said that while the situation seemed to be improving earlier this year, that progress has now reversed. "When I looked at the full dataset, it was clear that after months of steady increases, wage growth has started dropping, and this time the fall is much sharper."

September marks the 44th consecutive month in which wage growth has failed to keep pace with inflation. The BBS Wage Rate Index, which tracks earnings across 63 occupations in agriculture, industry, and services, shows that all eight administrative divisions recorded negative month-on-month wage growth in September. Khulna saw the steepest decline, down by 0.18 percentage points from August.

"Real wage erosion is deepening because inflation remains stubbornly high while nominal wages aren't catching up," Hussain said. "This is not just a statistical issue; it reflects the daily struggle of workers whose earnings are losing value faster than before."

Economist Mohammad Lutfor Rahman of Jahangirnagar University said the slowdown is linked to deeper problems in the economy: fewer investments, political uncertainty, and persistent inflation.

"Investment has slowed, and so has hiring," he said. "The number of workers hasn't gone down, but the number of available jobs has. When demand for labour falls and supply stays the same, wage growth naturally slows."

He said many businesses are holding off on new projects as they wait to see what happens after the upcoming national election.

"Businesses are following a wait-and-see approach. They want to know which government will come next and what economic policies will follow before they commit new money," he said.

For many low-income workers, the result is a shrinking household budget. The prices of food, rent, and daily essentials have risen so fast that even a pay raise feels meaningless.

"If this continues, millions of low-income workers could face serious nutritional deficits," Rahman warned.

According to a report released earlier this year by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) on Bangladesh, the number of people in Bangladesh facing high levels of acute food insecurity increased by 70 lakh to 2.36 crore in December last year, compared to 1.65 crore during the April-October period of 2024.

Rahman said the danger now is that falling real incomes will also weaken consumer demand, which could slow the overall economy. "We are seeing signs of a slowdown in trade, import-export, construction, and even in government development spending," he said. "All of this has combined to suppress labour demand."

Economists say the prolonged erosion of purchasing power could have wider effects on the economy. When people spend less, demand weakens, which in turn discourages businesses from expanding or hiring. This can create a cycle of slow growth and falling real wages that is difficult to break.

They say the situation requires coordinated policy interventions, including measures to boost labour demand and targeted support for low-income households.

"Without a meaningful slowdown in inflation or a boost in productivity, the real income squeeze will only worsen in the coming months," said Hussain.

Rahman is hopeful that better days will come after the national election.

"We, the economists, are hoping that after the upcoming national election, once a stable government takes office, labour demand will begin to rise again, and with it, wages will recover," he said.

In the meantime, he suggested two immediate measures for the government to cushion the blow for workers.

"The state cannot halt its essential development work. Infrastructure maintenance and road reconstruction must continue, because stopping them will create even bigger problems later," he said.

"There's no reason to wait for the next administration to fix broken roads or embankments. These must be repaired now. When the government steps in, it not only creates labour demand but also restores confidence in the economy," he added.

Secondly, he urged the government to expand food support.

"The worst effects of falling wages are felt by low-income workers. Providing basic food items at subsidised prices through open market sales programmes or rationing systems could help them cope with the inflation–wage imbalance," said the professor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments