Writing about writing, history, and Palestine

"The war might be raging in the streets, but it could never be defeated there, because what they were ultimately fighting was the word," writes celebrated and critically acclaimed American author, journalist, and activist Ta-Nehisi Coates in his latest nonfiction book, The Message. This single quote encapsulates not only much of what the book is about, but also one of Coates' own core takeaways from his journeys and experiences that he writes about in the book's three interconnected essays.

In The Message, Coates details several experiences from his travels to Senegal and Palestine, his correspondences with a teacher in South Carolina fighting against a school board's push to ban books with topics deemed controversial, and his personal takeaways from these events. In the book's first half, he examines a number of incidents from his childhood and teaching career, ruminating on the role of writers and the transformative capacity of their work. Woven in between recountings of conversations about Blackness and the history of a people with activists and writers in Dakar, accounts of efforts to stifle classroom discussions in Chapin, and harrowing details of the deeply structural violence of a two-tiered society in occupied Palestine, Coates writes about the power of writing itself. He describes scenes from his childhood, watching his father come home from being refused wages and sitting down to read—"Daddy says he reads to learn."

He describes learning very early on, about the immense potency that words hold, and the power an author has to not just convey ideas but to wholly reshape a reader's outlook. "The goal is to haunt— to have [the reader] think about your words before bed, see them manifest in their dreams, tell their partner about them the next morning, to have them grab random people on the street, shake them and say, "Have you read this yet?"" Coates' language is clear, his descriptions vivid—reading these accounts and his takeaways often puts the reader squarely in his shoes, standing in the writer's childhood West Baltimore home watching his father pull a book from a shelf, walking down a cobblestone road on Gorée, being stopped and checked by an Israeli soldier: Coates' writing haunts.

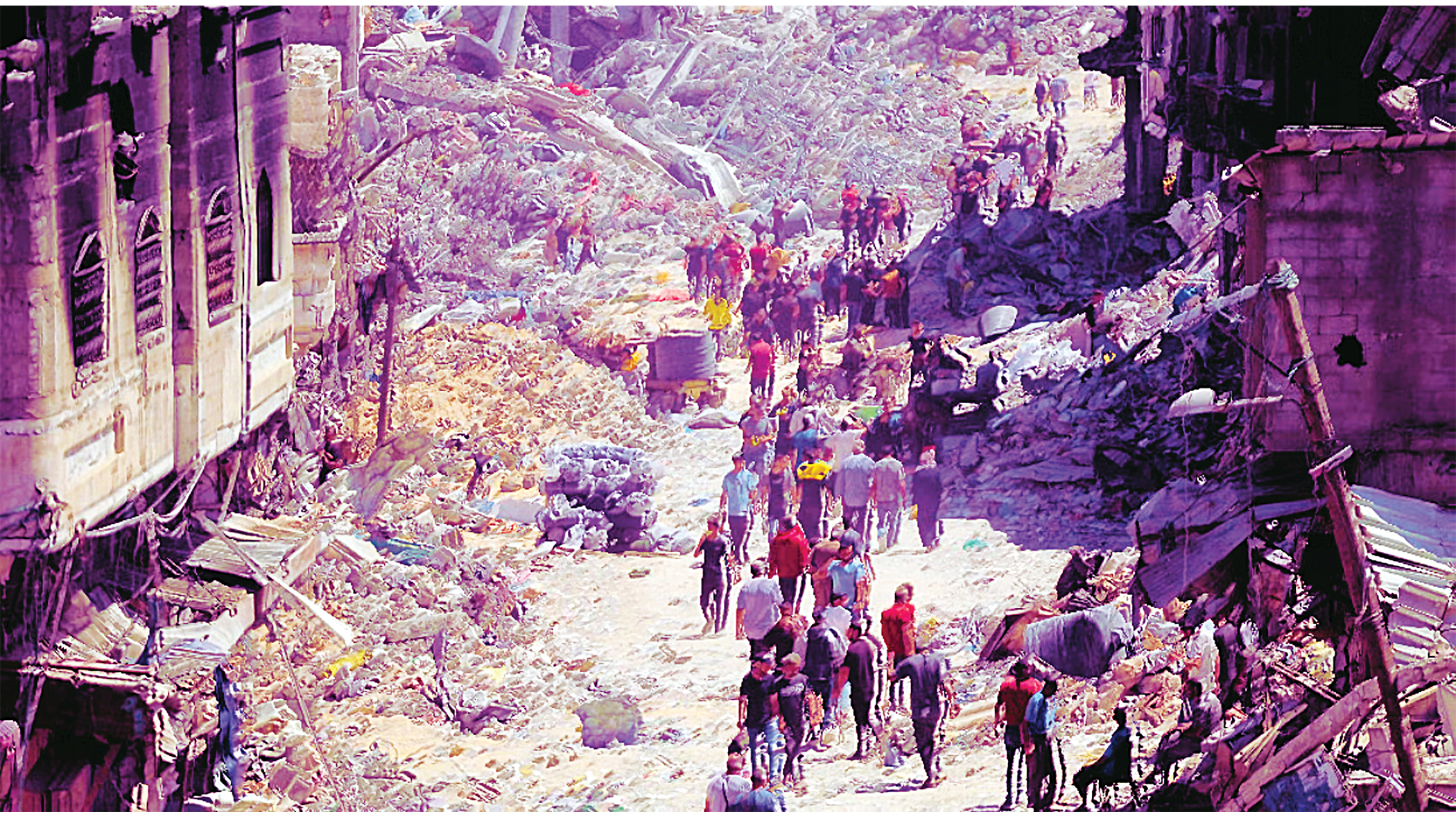

But with great power comes great responsibility, and those that wield the power of words have a responsibility to use them responsibly, to think about the stories they tell and how they can and do affect their readers' perceptions of entire peoples, of places, of reality itself. Coates ponders at length the role of journalists, of storytellers in telling the stories of real people in real conflicts around the world in the latter half of the book during and pertaining to his trip to Palestine. His accounts of the violence visited upon Palestinians by occupying Israeli forces on a daily basis lay bare a reality most of Western and particularly American media routinely obfuscates, and in his writing, Coates grapples with the responsibility writers and journalists have in telling these stories. "Editors and writers like to think[…] that they are independent, objective, and arrive at their conclusions solely by dint of their reporting and research. But the Palestine I saw bore so little likeness to the stories I read, and so much resemblance to the systems I've known, that I am left believing that at least here, this objectivity is self-delusion […] This elevation of complexity over justice is part and parcel of the effort to forge a story of Palestine told solely by the colonizer […]"

Coates has been a revered journalistic figure and notable progressive voice in American media for over a decade, and his work on race, history, and systemic inequalities in the US has not only amassed him a singularly dedicated base of fans who put a great deal of weight and respect in his words, but has importantly made him a voice in mainstream media that cannot be ignored. As such, the mere existence of this book and the pro-Palestinian advocacy therein do a fair bit to create cracks in the meticulously-upheld pro-Israel, pro-colonial false image of the genocide in the wider cultural consciousness. An example of a firsthand account of the book's contribution to changing people's views on Palestine, Etienne C. Toussaint writes in his article in Current Affairs magazine titled "How Ta-Nehisi Coates Helped Me See Palestine": "Reading the final chapter of The Message, I was struck by how my education had given me a narrow understanding of Israel as a redemptive response to the Holocaust, rendering Palestinians nearly invisible," and "Reading The Message shattered the careful framing that had once allowed me to experience my pilgrimage [to occupied Jerusalem] without moral conflict, exposing a reality far more complex than the sanitized narratives I had embraced."

Predictably, The Message was far from unanimously well-received. "The description of Coates's time in Palestine contains nothing that feels new to those sympathetic to his perspective, and nothing that would meaningfully challenge those who disagree, in part because he does not entertain any objections," writes Parul Sehgal for The New Yorker. On CBS Mornings in September 2024, Coates was confronted by host Tony Dokoupil about his presentation of the occupation, with Dokoupil calling the section on Palestine "not out of place in the backpack of an extremist".

Coates is far from infallible no doubt, and there are various valid criticisms of his work. As a notable example, American philosopher and socialist Cornel West wrote in The Guardian in 2017, "Coates praises Obama as a "deeply moral human being" while remaining silent on the 563 drone strikes, the assassination of US citizens with no trial, the 26,171 bombs dropped on five Muslim-majority countries in 2016 and the 550 Palestinian children killed with US supported planes in 51 days, etc." However, it is frankly painfully obvious that a majority of the pushback against The Message is from Zionist perspectives, with much of the criticism being discontent at Coates refusing to "both sides" the apartheid in Palestine. Some, such as Dokoupil, point to the lack of arguments made from the perspective of the Israeli occupation in favour of a "Jewish state", to which the author has firmly established his stance as being unequivocally against states built on ethnocracy.

For me, possibly the most important thing to note about the section on Palestine in this book is this quote on the very last page: "If Palestinians are to be truly seen, it will be through stories woven by their own hands—not by their plunderers, not even by their comrades." This frank admission by the author on the limited nature of his own perspective and the call for the need to amplify Palestinian voices is singularly critical not only in the context of a genocide that is now going on two full years, but in the context of our duty as readers to seek out firsthand perspectives and as writers to help bring these voices to the forefront. At its core, The Message remains a book written for writers above all else, as an exploration of the power and necessity of the stories we tell and as a reminder of the responsibilities we bear in doing so.

Arwin Shams Siddiquee is a writer, artist, and academic-in-training trying their best to keep learning.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments