The pond remembers: On visiting Lojithan Ram’s ‘Arra Kulamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum’

"I hate travelling and explorers. Yet here I am proposing to tell the story of my expeditions." Claude Lévi-Strauss opens Tristes Tropiques with this paradox, wary of the voyeurism that often accompanies travel yet compelled to reckon with the journey nonetheless. I carried that same ambivalence on my recent visit to Sri Lanka. I did not arrive as a tourist chasing beaches or colonial nostalgia, but as a seeker, curious about the textures of place, history, and memory through literature, visual culture, and lived landscapes. In reading Sri Lankan authors, I had already encountered the haunting reverberations of the civil war, stories often told in whispers, in absences. By sheer coincidence, I walked into an exhibition in Colombo that echoed these very undercurrents. What I found there was not simply art, but a deeply personal vocabulary of grief and endurance, offering a visual grammar for the silences I had previously only read.

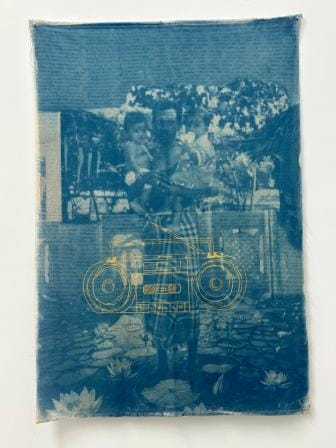

I walked into the Paradise Road Saskia Fernando Gallery, located at 41 Horton Place, Colombo, a gallery that felt less like a place to see and more like a place to feel, and found myself enveloped in blue. Not metaphorically, but truly and deeply. The air was heavy with the indigo tint of cyanotypes, those old photographic prints that soak up the sun and give back spectral images.

The exhibition, titled "Arra Kulamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum", was the debut solo of an artist named Lojithan Ram, aka, Ramanathan Parilojithan. Not just an artist, but a cartographer of absence, a memory-smith hammering his own past into forms both tender and ghostly. A Tamil from Batticaloa, eastern past of Sri Lanka, born into a community whose memories have been tattooed by civil war, Ram was not telling stories–he was exhuming them.

There was one cyanotype that caught me mid-breath. A fabric print, blue as old ink, fluttering slightly at the corners like it might escape its pins and fly. A man stood at its center, shirtless and strong, with two children resting on each hip. Behind him, a cascade of flora, a canopy of the past. Beneath him, a pond blooming with lotus flowers. It looked like a family photo, like something folded into an old album and hidden in a drawer of relics.

But then I saw it. Layered onto the photo, in gleaming gold lines, was a tape recorder. A boombox. Its symmetry cut across the image like a portal. Not nostalgia, I soon understood. Not just aesthetic play. This was his uncle. The one who sang the funeral chants, the Vaikuntha Ammanai, is that Tamil hymn of mourning sung for 31 days after a death. His uncle had recorded himself chanting these rituals. And when he died, the tape was played at his own funeral. The machine became the mourner. The voice, disembodied yet intimate, officiated its own exit. A resurrection, performed by cassette.

Ram took this memory, layered it into cyanotype, adorned it with lotus blossoms and ritual light, and gave us something that hovered between relic and vision. It was not just a tribute. It was an invocation.

This is the alchemy of Ram's work. The ordinary turned ceremonial. Family turned epic. Tape recorders turned gods.

Along a quiet wall of the gallery hung a series of works on old cement sacks, their surfaces bearing faint blue cyanotypes and golden silhouettes of everyday objects: a cactus, a chair, a flower, a kettle. These were not simply still lifes but acts of remembrance. The cement sacks came from Ram's childhood, when his father would collect them from construction sites, choosing the strongest ones to bring home. There, they were cut and folded into paper bags, a small family livelihood crafted by hand. Ram, as a boy, often helped in that process.

By returning to these materials, he honours that shared memory. The objects printed on them are drawn from daily life but transformed through memory and labour into something sacred. What once held building materials now carries the traces of a household's quiet endurance. The artworks shimmer with tenderness. They speak of making do, of making meaning, and of a bond between father and son that lives on in paper and ink.

His art becomes a geography of loss. Not a personal loss alone, though it certainly is that, but a collective cartography of erasure. Civil war, displacement, disappearances. A nation that cannot remember its wounds tries to pave them over, and here comes Ram, peeling back the asphalt and revealing the bones underneath.

And then there is the title of the exhibition. "Arra Kulamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum", a verse borrowed from Avvaiyar, the ancient Tamil poetess, whose lines speak of a dried-up pond. The birds flee when the water disappears, but some aquatic plants remain. Kotti. Āmpal. Neythal. Their roots dig deep into cracked soil. They do not escape. They endure.

This is the metaphor Ram has chosen, and perhaps the one that has chosen him. His art is not about survival in a triumphant sense. It is about rootedness in the absence of sustenance. The clinging of memory to barren ground.

Ram's sculptural series Poigai works like a memory pond. Objects float or sink within imagined lotus landscapes. A bicycle stands with a stack of papers balanced on its rear, an offering to his father who once pedaled through life with persistence and poise. A bed blooms with lotuses, transforming sleep into sanctum. These objects, so ordinary, become altars. Their dailiness becomes their divinity.

It struck me that what Ram has done is to reassign the role of memory from the realm of thought to the realm of form. You do not merely remember these things. You see them, smell them, feel the edges of their weight. They become as tactile as mourning itself.

There is a certain stillness in his work, but it is a deceptive stillness. Beneath it, there is an ache. That ache is not loud. It doesn't wail. It murmurs. It seeps in like humidity. You don't realize it has soaked you until you are wrung out.

And yet, his work is not hopeless. That would be too simple. Ram does not paint grief without its twin, love. He does not mourn without memory. He allows for longing, for reflection, for the possibility that even absence can be a presence of sorts. It is a form of devotional art, not in the religious sense, but in its attentiveness. He worships the memory. He enshrines the mundane. He tends to the invisible.

As I moved through the space, I began to understand that this was not just an exhibition. It was a ritual. A visual liturgy. The cyanotypes were prayers. The sculptures were offerings. The gallery itself had transformed into a pond of recollection, and we, the visitors, were either the birds that fly away or the roots that stay. I did not know which I was, but I knew I would carry the blue with me.

What Ram gives us is not a story with a clean ending. He does not offer a resolution. He offers a landscape of longing. A space where belonging is uncertain, and home is not a place, but a sensation revisited over and over again. His work recognises the ache of impermanence, the fact that everything can be lost, and yet insists on the beauty of what remains.

I left the gallery not with clarity, but with questions. I thought of the pond. I thought of the plants. I thought of the boombox playing its sacred chant into the silence. I thought of my own family, of my own ghosts, of the photographs I've forgotten to look at for years.

Ram does not ask us to mourn with him. He asks us to listen. To the pond. To the chant. To the cassette that rewinds itself over and over until the voice of the dead becomes part of the living again.

In a time where spectacle often overshadows sincerity, where art sometimes forgets its heart, Lojithan Ram offers a whisper. A blue whisper. And in that whisper, you may just hear your own name.

Naseef Faruque Amin is a writer, screenwriter, and creative professional.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments