Adaptation as misrecognition: ‘Siddhartha’ between text, philosophy, and stage

There is always a subtle tension when a story migrates across cultures. Some narratives travel with the lightness of wind, reshaping themselves almost effortlessly inside new imaginations, while others arrive heavy with the weight of the worlds that first produced them.

28 November 2025, 19:30 PM

The risk of becoming: Notes on translation and transformation

Translation is risk, and poetry is the highest form of risk

7 November 2025, 18:33 PM

Fragments of resistance: The counter-archive of Mohammad Idrish

To understand Idrish is to approach it as more than a documentary. It is a meditation on how cinema can bear witness, reactivate memory, and ignite resistance. The film stands at a crossroads where the insights of critical thinkers illuminate its form and force.

15 September 2025, 13:58 PM

Because no one asked: Archiving the Rohingya past

It began with a question, the kind of question that arrives quietly, almost like a sigh.

5 September 2025, 18:00 PM

The Hand and the Nation: Reading Nasir Ali Mamun’s Portraits of SM Sultan

“Photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe.” — Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), p. 3.

28 August 2025, 12:54 PM

The pond remembers: On visiting Lojithan Ram’s ‘Arra Kulamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum’

In a time where spectacle often overshadows sincerity, where art sometimes forgets its heart, Lojithan Ram offers a whisper. A blue whisper. And in that whisper, you may just hear your own name

11 July 2025, 18:59 PM

The Terrible Splendour of Not Knowing

“O my body, make of me always a man who questions!” — Frantz Fanon had thundered, as if pleading with flesh and sinew to refuse silence, to resist obedience.

3 July 2025, 09:07 AM

‘Pakhider Bidhanshabha’: A mesmerising theatrical odyssey

On the evening of February 10 the curtain fell for the last time on a performance that, over the preceding days, had cast an enchanting spell upon its audience.

14 March 2025, 18:00 PM

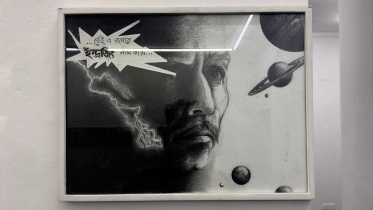

A counter-narrative of ‘Meghnad’: Reflections on Kabir Ahmed Masum Chisty’s exhibition

As I walked into Kalakendra in the capital’s Lalmatia area, I was unsure what to expect from Kabir Ahmed Masum Chisty’s solo exhibition, “Meghnad Badh”, curated by Lala Rukh Selim. I did not personally know the artist or his body of work, yet I was drawn to the premise—a visual reimagining of “Meghnadbad Kabya”, Michael Madhusudan Dutt’s magnum opus that transformed the perception of a character largely dismissed in the mainstream “Ramayana”. What struck me most was the exhibition’s engagement with what Sibaji Bandyopadhyay, in his book “Three Essays on the Ramayana” calls ‘dispersed textuality’—the idea that an epic exists not as a singular, authoritative narrative but as an intricate, layered text that absorbs contradictions and alternative voices.

5 March 2025, 13:59 PM

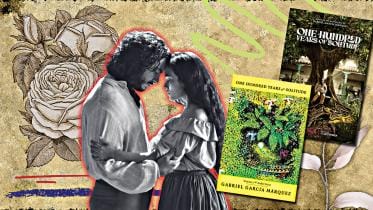

Translating magic: Netflix’s bold journey to bring Macondo to life

Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude (originally published in 1967) has long been heralded as a masterpiece of magical realism and a cornerstone of Latin American literature.

25 December 2024, 18:00 PM