7 minutes to midnight

Often in midnights I open the Nuke Map and type Dhaka. It's a very detailed map, it tells you to select your nuclear weapon of choice, they are so much shinier and bigger now! Like putting a jar of syrup in the shopping cart standing in a supermarket aisle, I choose one. The map calls the streets by names, and I see the roads I took to reach home yesterday steadily going siren-red, and air raids begin to fill the pit of my stomach. And then there's nothing and no one. Which is bliss, I suppose. Would that world be worth surviving?

It was July, 1947.

The endless ancient shrines of Kyoto we see today would be spared in a minute.

In high-end war rooms, generals with more badges than they could bear had the map of Japan hanging over them since July 16, the Trinity Test.

They made a list of cities and were debating which ones would be most suitable to host Oppenheimer's magnum opus. The cities didn't know they were hosting it. And Kyoto, though it was on the top of that list, didn't make the final cut.

Hiroshima did.

Nagasaki did.

I imagine it's no easy feat finding a home for the first-ever nuclear bomb. You don't wanna waste a perfectly good bomb! It took 2 billion to develop it, how can you not use it, and you kinda wanna see what it does. Their god isn't known for subtlety.

In later declassified documents, we see their priorities in selecting the cities. It has to be a large urban area with mostly civilians in it, of course! Somewhere between Tokyo and Nagasaki. Something that already hasn't been bombed out.

We see that the targeting committee has to beg the air force to stop bombing cities, to reserve targets just for the Manhattan Project. The US war secretary Henry Stimson tells the president he's afraid Japan has been bombed so much that a new weapon "would not have a fair background to show its strength."

The plane to Hiroshima was named after the pilot's mother, Enola Gay. And the bombs lovingly, Little Boy and Fat Man.

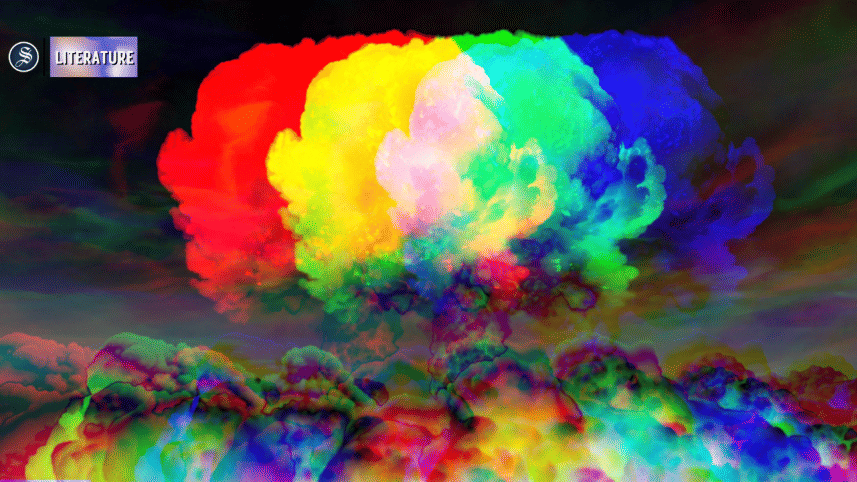

When the houses of Hiroshima made of wood and paper went up in flames–which was a past, which is now, which is a present and always will be–Dr Strangelove grovelled off his wheelchair and saluted the generals and someone shouted, "Gentlemen! You can't fight in here. This is the war room!" And we learned to stop worrying and love the bomb. In this past, present and future, the end of humanity has never been so advertised. As we cannot look grief in the eyes and have covered our faces with scrolling screens, it is clear we prefer to be deers caught in red light, makes life more interesting, no?

As we cannot look anything real in the eyes anymore, there is this fear that nothing here remains to be seen. History is finished. We already know the future because we've seen the past. What this post-nuclear power-fueled world has done is that it has snatched the sweet gift of uncertainty. We have to know. We know. There are no news bulletins, it's a 24-hour dramatisation of the end of the world.

A human being is the tiniest colony of history. So what any of us is doing, is what history is leading towards. This scripted humility and corporate-mandated niceness that we have going on now will make sure we stay dazed. If we stay dazed we can't feel it, and if you can't feel it, it's not real, is it?

In our nuclear thriller, this clock exists. It was designed in 1947 by artist Martyl Langsdorf, wife of Alexander Langstorf Jr, a Manhattan Project scientist. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists sets the clock every few years to show how much time we have left until midnight. Midnight is nuclear armageddon. It assesses the risk of total human obliteration. And it is quite obvious we love midnight–can't get enough of it.

Now, for simplicity's sake let us believe in heroes and villains, gods and monsters. Oppenheimer, our man of the left with his reading of French poetry and Bhagavad Gita, the Prometheus, the pink but not quite red comrade, started developing the bomb because the Nazis had to be defeated. So isn't it ironic that it dropped after the Nazis surrendered? And when a deeply guilty man aware of his actions goes on to say that it should never be used again he found out it's not easy being America's pet. America will throw you away without skipping a beat.

Let's be clear, he lived a pretty decent life even after America wasn't so fond of him anymore. This isn't a story of Galileo, or Copernicus. And a bomb big enough to end wars is just a line one says to soothe one's conscience.

And it wasn't a Führer exclusive, the cruelty of the second world war. The Allies and the Axis overlapped quite often and it is important to know how history tells the story of the victors. It has been almost 80 years without a war, it could be argued. So, Oppenheimer was right, it could be argued. Except for Vietnam, Korea, the entire middle east and Syria are now and have been in infernos. The plan to essentially ban nuclear weapons and have an international community monitoring them have failed miserably. And remilitarisation all over the world is gaining at godspeed.

Two times it happened when an almost nuclear armageddon was avoided due to the decisions of two human beings. The first was during the Cold War, by Vasili Arkhipov, who was second in protocol. He vetoed a counterattack even after the sensor on the board told that America had launched a missile. He made a judgement call that this couldn't be it and refused to fire back. He was right. And two decades after the Cuban missile crisis, Colonel Atanislav Petrov did the same.

Now the nuclear arms race is here with the development of AI. Can an AI be our Vasili Arkhipov, our Atanislav Petrov?

The greater common good is the best excuse "people running the show" have come up with so far. So in the name of that, the policy of mutually assured destruction will carry on. Will carry on the many peace conferences and promises and treaties. While the mass, the 'we', by just virtue of being in this time, know that nothing is ironclad, no words have to be kept. People say things because sometimes the moment demands it, and as the moments pass people go off to new words.

So when during midnights I see Dhaka in red, I try to visualise the atom and I almost can. I look at my fingers and try to map the connecting dots, and almost can. Stupid pages of beloved books say, have a person to see this one out with. With your unuttered kisses that didn't have time, and your unironic love that didn't find places.

Guys, for real! Dhaka would never be the main target of a perfectly good wealthy precious bomb. No, we'll be a by-product of the armageddon. Like the Famine of Bengal during the Second World War was. And in exchange for the presidential suites at the Ritz and so on, the men holding our city keys have already opened our skies to all that may come. So say Amen, say pollution is progress. Say, now it's not an old-school death. Death is now a metalhead with a killer sense of humour and life's a sellout. And it's all so cool!

Say, maybe they'll name the next ones Cutie Pie and Jesus Christ Superstar.

Say, the next mother's name painted on a plane like graffiti would be Mary.

This planet is still pale blue. It is still a dot in the Akashganga.

And we are still ready to drink venoms with our biodegradable straws as long as it comes in nice packaging.

So here comes the end of this piece that started in the past, started with a lie, it's not seven minutes to midnight, it's now 100 seconds to midnight.

This is the closest we've ever been to midnight in the clock's 75 years of existence.

And when the mushroom cloud rises higher than heaven we will say it's God taking a photograph!

Sumaya Mashrufa is a writer and an artist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments