Kolkata, unplugged

Not many cities can claim to inherit a thickly layered palimpsestic past, which Kolkata has been a witness to over the last 300 years. As the city grows from a tiny geography of three villages, into a megapolis of size and splendour, it acquires a visceral sensibility that seeps into the bloodstream of its residents who, even as they migrate, continue to feel it in their pulses. Once the space turns into an abiding topophilic sentiment, it excites the sensitive residents to break into poetry—poetry of self and space—with one seamlessly coalescing into the other. Writing the city becomes an act of self-witnessing, an inward journey into one's own emotional make-up.

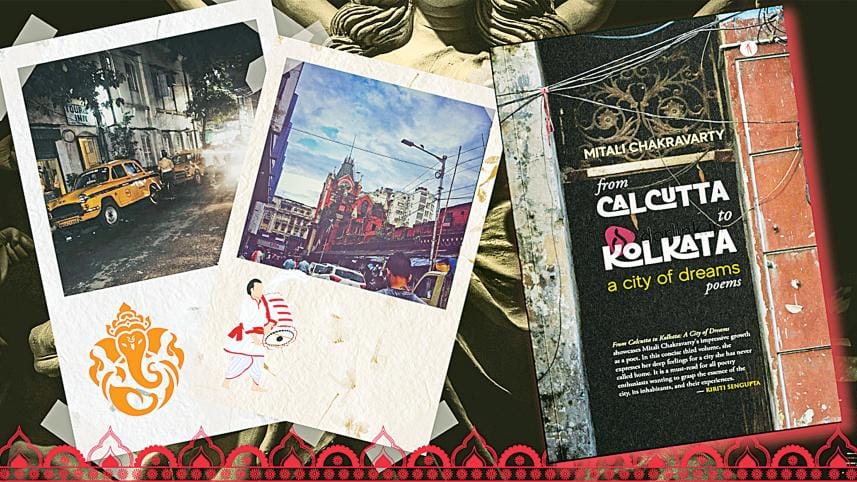

Mitali Chakravarty's latest collection of poems, From Calcutta to Kolkata: A City of Dreams, is not an ordinary chronicle of a city, it is a 'sthalpuran'—a sustained act of cultural cartography, never attempted before. Writing more than 75 poems on a city that is perpetually on the move, literally moulting its skin every season, or renewing its feminine energy every Durga Puja cycle, is an act of immersive plunge that redeems both the city and the poet in reciprocal ways.

The poems in the collection are not easy panegyrics, nor are they plaintive requiems. Each poem is a snippet of the city—its animating inner recesses, its informal convivial addas, its monuments of unageing intellect—traversed, and felt first-hand. The poet travels through the city as much as the city travels through the poet. Local anecdotes, hearsays, micro-histories, literary asides, street murmurs, and familial whispers—all that is usually filtered out of standard, chronicles as unreliable and turns into ready material for poetry which is both persuasive and compelling. The love lore of heroic Job Charnock with his widowed bride Maria—a Rajput princess rescued from a funeral pyre—recounted in a Jatra performance during a festive night is an occasion enough for Chakravarty to lapse into a poetic ecstasy. Forgoing toxic debates of Orientalism, she approaches the city as a sensuous woman that lures, and is lured. In a telescopic swoop, the poet writes, "Love sprouted the City of Joy", connecting Charnock's legend with Dominique Lapierre's 1985 catchy description of Kolkata as the 'City of Joy'.

Born around romance, Chakravarty's Calcutta grows to acquire its own palpable textuality, its semantic surplus, and its enabling ambivalences that defy explanations: "Google map gets lost/ in narrow by-lanes" (from "Dumdum"). While the garden of Jorasanko—Tagore's ancestral home—is abuzz with the knotty stories of Bhanu and Kadambari; the lanes on way to this bastion of the 'bhadralok' bear testimony to "neglected lives" ("On the Way to Jorasanko"). Calcutta is a cosmopolis of contradictions—that it raises "a rampart, /a fortress for devis/ but leaves only broken/ roads for Monobina and Jahanara?" ("Monobina"). Layered with its own set of "opposites and in-betweens", the city smiles like an enigmatic Monalisa ("Monalisa?"). The contradictions are not entropic enough to throw Calcutta out of gear–"Here, poverty does not cloy, /does not destroy. But creates/ kintsugied art that touches heart" ("Kintsugied"). Gastronomically speaking, the Gourmet City "digests all cuisines", which it devours "with devotion and delight" ("Chelow Kebab"). The 250 years old Banyan of the Bengal Presidency "spreads/ its foliage to home diverse/ lives, despite lightnings, storms." ("The Great Banyan").

Mitali's poetic drift is not racy, it is not without punctuations. Her Calcutta celebrates life with "long pauses for siesta and adda" ("Calcasians"). Instead of invoking the idiom of the usual apocalyptic collapse or irreversible dystopic dystrophies, she remains non-melodramatic—a stoic with a smile. The raging super cyclonic storms—from Amphan to Dana—that rise in the Bay of Bengal do cast their gloomy shadows, but the city evinces resilience: "Ripping old stories for new, /the tornado grows till it/ exhausts unto a steady flow." ("Longings"). Even "seashells that smile at the sea" embody spirit of the city as they "murmur softly, / eternal proof of/ resilience to death" ("Waiting..."). Tagore, Nazrul, Teresa—as conscience keepers of Calcutta culture—keep knocking the poet's inner body sensorium as reminders of a robust past. What informs the self-reflexive poet in moments of such stalemate are the words of wisdom uttered by some unnamed guru: "Time past—one guru had said—is/ contained in time present and future" ("Buddha in Kolkata"). In such a temporal back-and-forth moment, the city turns into an archive in flux, a tale in motion, "a single life trying to/ override the eternal soul"—defying standard logic of linear progression.

The collection is not just about the people of Calcutta, it is also about its geography, its seashore, its ghaats, its trees, and even its traffic, which collectively weave a narrative of belonging. The poet yokes together history and geography of the city into one continuum: "We will never know/ for tied to geographies,/ histories grow roots/ that defy clouds" ("Buddha in Darjeeling?"). She hears "the hoofbeats of history" in the soil of the land. Mitali Chakravarty does not offer an easy narrative of 'Calcutta versus Kolkata'. She underlines the embeddedness of one into the other: "Kolkata now stays/ embedded with its/ bedrock in Calcutta, /..." The changes are suggested, but in the form of mild-mannered open-ended questions – "Calcutta was born/ of love, yet Kolkata/ weeps lovelorn? Why? / Why does Kolkata cry? ("Why does Kolkata Cry?"). Elsewhere, the same poetic trope is used: "Calcutta was safe –/women walked tall. /What happened to/ Kolkata of zillion/malls and walls?" ("The City Whispers"). Kolkata frees the poet; it binds her as well.

A city which has been infamously described by a range of writers as "a dying city", "a widow in the white sari", "a slow boiled sewer", or as "a Great Black Hole" of urban India, is reclaimed by the poet as a city "that glows with humanity's overflow, never overcrowding". It is with such redeeming equipoise that the poet rediscovers the city and its people—known for their "certain sense of humour/ that stays, acerbic yet friendly". The readers of the poems feel the pulse of the city as they navigate along with the poet through its bustling bylanes and busy boimelas, museums and mutts, colleges and coffee houses. Some images stay back and reverberate in the mind, and one among them is: "Now, a pigeon sits on her head" ("Bengal Presidency"). It caricatures the Empire, it lends wings to a post-colonial city, no longer reeling under the pressures of a capital of the nation.

Mitali Chakravarty is a serious poet; she would add to her repertoire of emotions if she could harbour the playfulness of the Eden Gardens or Kolkata Derby within her poetic radar.

Prof. Akshaya Kumar is a professor of English at Panjab University, Chandigarh. He received critical attention for his book, Poetry, Politics and Culture (Routledge, 2009) and his co-edited volume, Cultural Studies in India (Routledge, 2016).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments