Aparna Sanyal and the burden of representation in South Asian literature

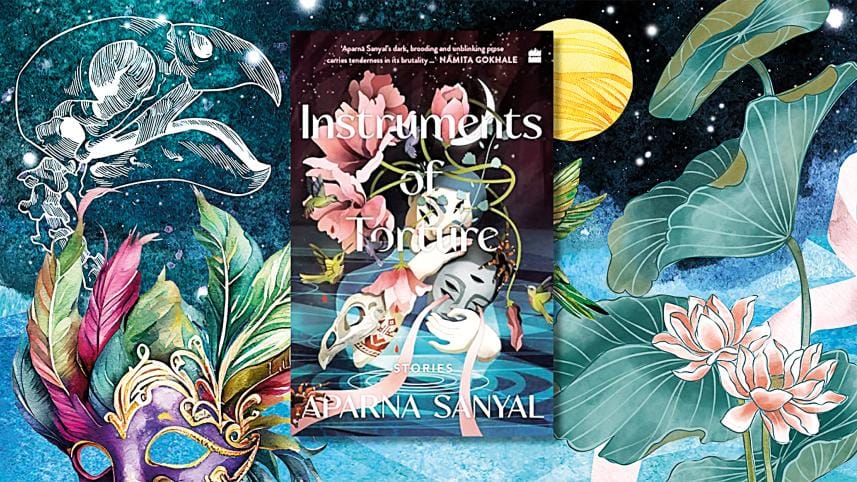

Aparna Upadhyaya Sanyal's Instruments of Torture is a powerful literary collection that delves into the psychological and societal torments individuals endure, particularly focusing on themes of beauty standards and the representation of women. Each story in the collection is named after a medieval torture device, serving as a metaphor for the emotional and societal pressures faced by the characters.

For instance, in "The Spanish Boot", the protagonist, Poornima, grows up internalising the belief that a woman's value is intrinsically tied to her appearance. Her life revolves around maintaining her beauty, a notion instilled by her mother and reinforced by societal expectations. This narrative mirrors the experiences of many women who grapple with the relentless pressure to conform to idealised beauty standards. Similarly, in "The Rack", Sanyal introduces a man subjected to medical interventions aimed at "curing" his dwarfism. His anguish highlights the societal pressure to conform to physical norms, underscoring the psychological toll of such coercion. These stories serve as sharp commentaries on the structures that shape our lives, often to the detriment of the most vulnerable.

Sanyal's exploration of these themes aligns with broader discussions in South Asian literature that critique the role of beauty in determining a woman's worth. Writers such as Ismat Chughtai, Kamala Das, and Jhumpa Lahiri have all engaged with these issues, portraying the ways in which women's bodies become sites of control, admiration, and sometimes even rebellion.

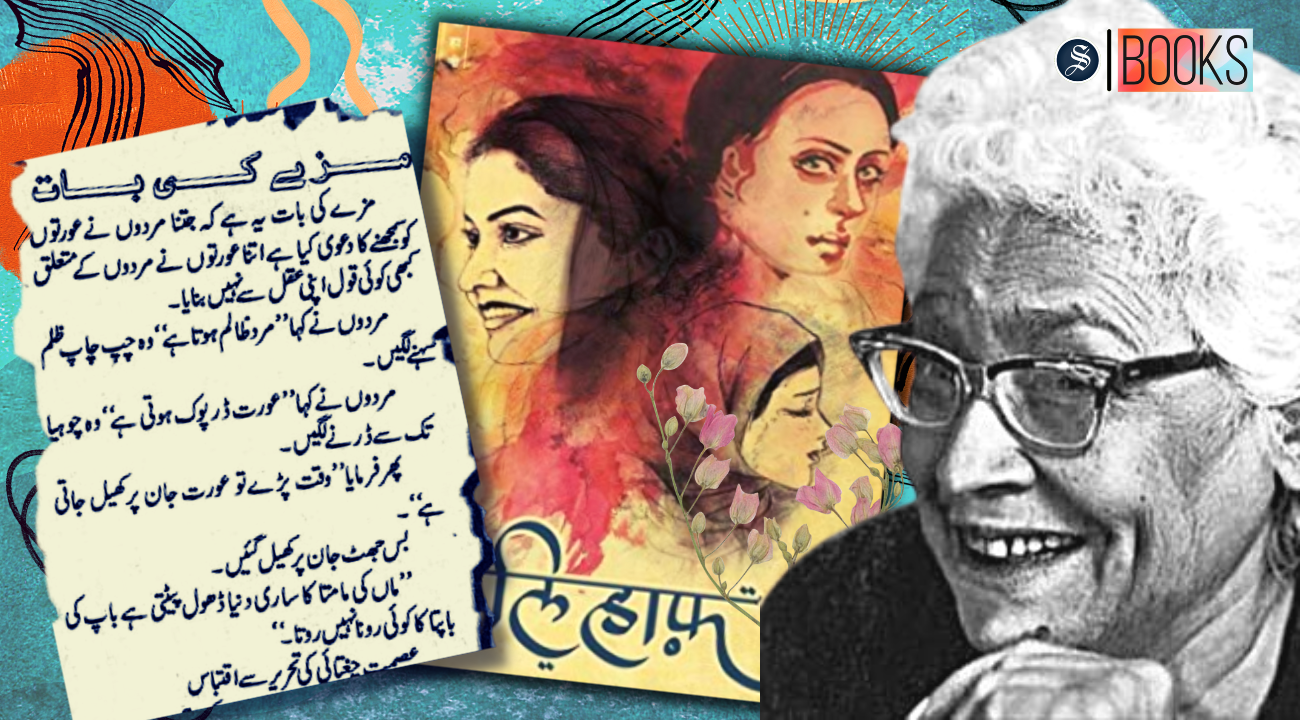

Ismat Chughtai's Lihaaf (1942), though not directly about beauty standards, challenges the idea of a woman's prescribed role in a patriarchal society. The protagonist, Begum Jaan, is married off to a wealthy man who shows no interest in her, leaving her to find solace in an unconventional relationship. Chughtai exposes how women are often reduced to their physical appeal and expected to conform to societal roles that do not necessarily serve them. Similarly, Kamala Das's poetry frequently grapples with themes of bodily autonomy and the tension between societal expectations and personal agency.

Jhumpa Lahiri's Interpreter of Maladies (1999) also provides a nuanced critique of gender roles, particularly in the South Asian diaspora. In the short story "Sexy", a woman named Miranda becomes infatuated with a married Indian man who only sees her as an object of desire. Lahiri, much like Sanyal, interrogates the ways in which women's appearances are fetishised, whether through colonial exoticism or internalised cultural expectations.

Sanyal's themes resonate with the works of artists and writers from around the world who have critically examined societal perceptions of women and beauty. Frida Kahlo, for instance, used her art to challenge traditional feminine beauty standards and the male gaze. In her self-portraits, Kahlo emphasised features like her monobrow and upper lip hair, embracing unconventional beauty norms and subverting societal expectations. Her painting, "My Nurse and I", candidly portrays the complexities of breastfeeding, highlighting the often overlooked pain and disconnect associated with the experience.

Ana Mendieta's Silueta Series also reflects on identity, femininity, and the societal constraints imposed on women's bodies. Mendieta created female silhouettes in natural settings, expressing a deep connection between the female body and the earth. This work mirrors the way Sanyal's stories reclaim the female experience, portraying pain and resilience in equal measure.

Contemporary artists Mickalene Thomas and Linder further explore feminine imagery and societal expectations. Thomas's monumental portraits of Black women celebrate their strength and agency, blending personal and cultural narratives to challenge traditional representations. Linder's post-punk photo collages dissect feminine images from soft-porn and fashion photography, offering a critique of the roles and perceptions assigned to women.

In the South Asian literary tradition, beauty has long been a determining factor in women's futures, especially in terms of marriage. The trope of the "dusky" or "dark-skinned" woman struggling for acceptance appears frequently in literature and cinema. From Rabindranath Tagore's Chokher Bali (1903) to more contemporary works like Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things (1997), women's appearances often dictate their societal standing.

Sanyal's Instruments of Torture engages with this theme by exposing the oppressive beauty standards imposed on women from an early age. In "The Spanish Boot", Poornima's life is shaped by the pressure to maintain her looks, a reality that many South Asian women can relate to. In a region where fairness creams are still marketed aggressively and marriage proposals are often contingent on a woman's complexion, Sanyal's critique is particularly poignant.

Moreover, the idea of women's bodies as battlegrounds is not new in South Asian literature. From Amrita Pritam's Pinjar (1950), which deals with the Partition's impact on women's autonomy, to Mahasweta Devi's Draupadi (1978), where a native woman is subjected to state violence, female bodies have long been sites of suffering and resistance. Sanyal extends this discourse by linking beauty standards to psychological torture, showing how internalised oppression can be just as damaging as external violence.

While Instruments of Torture focuses heavily on beauty standards, its commentary extends to other forms of societal oppression. Sanyal's use of medieval torture devices as metaphors allows her to explore how outdated, yet persistent, structures continue to shape contemporary lives.

For instance, in South Asian societies, the caste system continues to dictate people's opportunities and social mobility. Although not directly addressed in Instruments of Torture, the idea of rigid societal expectations forcing individuals into predefined roles aligns with the caste-based discrimination explored in Dalit literature. Writers like Bama (author of Karukku) and Perumal Murugan (One Part Woman) have similarly highlighted the ways in which societal expectations can become oppressive "instruments of torture".

Sanyal's work also speaks to the universal experience of bodily scrutiny, a theme that transcends geography. Whether through the lens of South Asian marriage markets or Western beauty industries, women are constantly subjected to impossible standards. By framing these struggles through the language of historical torture, Sanyal underscores their severity, making readers question whether so-called "normal" expectations are, in fact, a form of violence.

Aparna Sanyal's Instruments of Torture is a compelling critique of the ways in which beauty standards, societal norms, and patriarchal control shape individuals' lives. By drawing from historical torture devices, Sanyal forces readers to confront the brutality of these expectations. Her work aligns with global feminist discourse while remaining deeply rooted in South Asian literary traditions, making it a significant contribution to contemporary literature.

By examining Sanyal's work alongside those of Chughtai, Das, Lahiri, Kahlo, Mendieta, and others, it becomes clear that the pressure of beauty and societal perceptions of women are pervasive across cultures. Artists and writers continue to challenge these norms, offering new ways of understanding identity, femininity, and resistance. Sanyal's work, in particular, stands out for its sharp metaphors and unflinching critique, making it an essential text for discussions on gender, representation, and power in South Asia and beyond.

Namrata is a writer, a digital marketing professional, and an editor at Kitaab literary magazine.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments