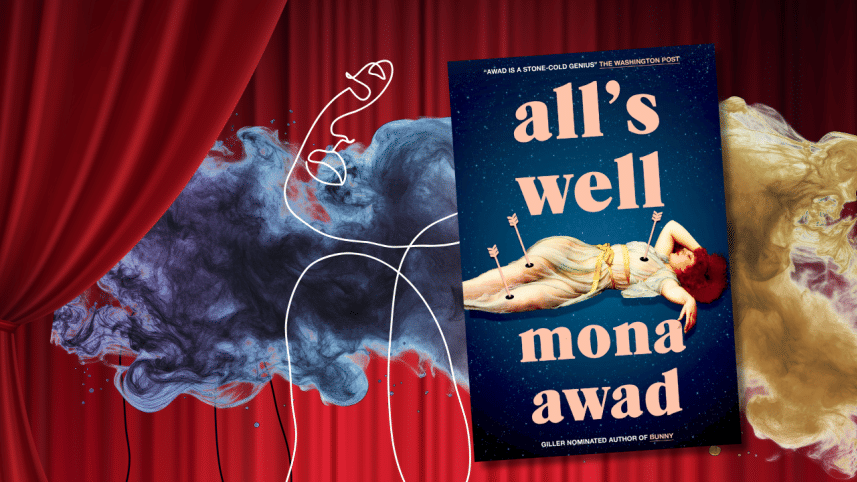

All’s almost well

I'd already read Bunny (Viking, 2019), so this time I knew what I was in for. Awad's worlds have rules of their own, and once again, she demands your suspension of disbelief properly suspended. In Bunny, reality bled through an MFA program; in All's Well, it's the theatre department of a small college. If Bunny was Mona Awad's culty campus-horror about belonging and performance, All's Well turns chronic pain into a play that devours the stage like it's the main character in this Shakespeare classic. "How amazing would that be? Each of us flushed and grinning in the spinning dark of our own overturned world?" says Miranda Fitch, our unreliable and unrelenting heroine for this one, and she is stuck in a one role no one completely believes.

As a lit major, I was already primed to enjoy the book. I managed quite a few embarrassingly smug thrills every time I caught a Shakespearean wink. Of course there's the titular Shakespeare play, then there are the three mysterious men at the bar who offer her a deal very similar to the one Doctor Faustus is offered as well, and much like Stoppard's duo wanders half-aware of their scripted fates through the plot of Hamlet in the play "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" (1996), Miranda also waltzes between reality and nightmare logic—directing this semester's live rendition for All's Well, a play about a woman who heals a man while she herself has the displeasure of waking up everyday and having to limp her way into the auditorium. And everyone around her—her ex-husband, the doctors, her students, her colleagues—they all treat her with a brand of patronising disbelief that seems to be reserved for women who refuse to suffer quietly. And aside from all the literary allusions and nods, there is something infuriatingly familiar about that pain.

A few years ago, I developed this horrible wrist pain that turned every Finals season into my own personal biannual hell. One doctor said it was rheumatoid arthritis, another said my bones were eroding, another said I was calcium deficient until we looped back to arthritis again. All I knew was that I was in constant agony for my equally agonising four-hour exams, swallowing painkillers like TicTacs and dunking my wrist in ungodly dollops of pain-relief creams and ointments. And every time I found myself in front of a different doctor, I couldn't help feeling a strange need to almost perform my pain, and react a bit more to the physician squeezing my wrist to see how much it hurt. Of course a wrist that hurt only occasionally is nothing compared to chronic pain that a lot of people have to endure on a daily basis, but Mona Awad really gets the performance of this aspect. Miranda is constantly dismissed because her pain doesn't fit the script. It has to be legible enough before it is believed. Even pain must be interesting for it to make sense, especially because our culture loves a good suffering—but so long as it is done just right of course.

Culturally, we've built an entire mythology around characters who fall apart just right. Whether it is Nina stabbing herself in Black Swan (2010), or Andrew bleeding his hands out on his drum kit in Whiplash (2014), or even Britney Spears shaving her head in 2007—pain only makes sense when it is a performance, but that performance has to be staged with precision as well; it cannot be too messy to ruin our comfortable consumption of the whole thing. After all, Nina bleeds out, Andrew is still trying to appease his abusive mentor and Britney Spears became the punchline for late-night host monologues for years to come. And still we have deemed this necessary for art and performance to matter. We package and present suffering so others might applaud it. It's the cult of suffering for your craft, that pointless yet extremely seductive lie that pain is the most important proof of authenticity. Miranda also wants her pain to mean something, because otherwise she is just a washed up, has-been theatre actress past her prime. Her students mock her limp. Her superiors patronise her. Because it is an annoying limbo after all— the only way she can be taken seriously is if her pain is beautiful. Otherwise, all you're offered are unfunny jokes on late-night network tv.

All's Well circles one maddening question: what does pain need to look like before someone finally believes you? And how do you stop before it gets too discomfortable? Her students want a version of her that's easier to mock, her colleagues want a version of her that's easier to manage, and her doctors want a version of her that fits neatly into a chart. Miranda keeps failing that performance, and because she fails it, the novel slips into something a lot stranger. Reality starts to thin out as the scenes grow more off-kilter. One moment we're in a faculty meeting, the next we're stuck in the middle of something that feels like a fever dream suffocating for control in a black box theatre. And by the end, it's almost impossible to tell whether Miranda is losing her grip or the story is losing itself.

As per Awad's M.O., the book refuses to let you decide what's "real". As the reader you can never clearly tell when Miranda isn't playing along. It's disorienting in the exact way pain is disorienting. It makes everything slightly unreal, like you're watching a world tilt one degree at a time.

And by the end none of it really feels rational anymore. There is Miranda pinned to the floor, her body hijacked by pain so intense it becomes a special effect, while the fat man saunters onstage transformed into a glowing version of himself. The cheap mic is wrapped in fake roses and the room vibrates with an old-Hollywood Judy Garland show tune that Miranda's mother used to sing for her. The whole thing plays out like the Club Silencio scene in Mulholland Drive (2001), and when you reach the end, it doesn't quite feel like you've read a novel about a theatre professor with a broken hip.

It is hard to say which parts were real and which parts were rehearsed. Nevertheless, the scene cuts and the book ends, and you're left wondering when, exactly, the proverbial wallpaper had started to move.

Arshi Ibsan Radifah is a literature major who loves unreliable narrators and Wes Anderson movie sets. If she had it her way she would have liked to play bass for a girl band in the 90s, but for now she'll suffice by rewatching Empire Records.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments