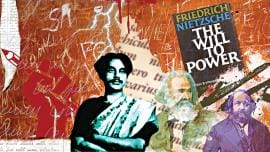

ESSAY / Symphonic overtures of Nietzsche-Marx-Bakunin in Nazrul’s ‘Bidrohi’

10 January 2026, 00:00 AM

Books & Literature

ESSAY / On mothers, monsters and myths: A look at the Mary before the Mary

5 December 2025, 18:57 PM

Books & Literature

ESSAY / Lessons from our literary girls: Why freedom framed as favour is no freedom at all

3 December 2025, 18:00 PM

Books & Literature

ESSAY / Lessons from our literary girls: Why freedom framed as favour is no freedom at all

26 November 2025, 11:18 AM

Books & Literature

ESSAY / When old patriarchies wear new faces

25 November 2025, 12:57 PM

Books & Literature

ESSAY / Taylor Swift talks back to Shakespeare

19 November 2025, 18:00 PM

Books & Literature

ESSAY / Two awakenings: Reading ‘Dhorai Charita Manas’ and ‘Things Fall Apart’

14 November 2025, 20:03 PM

Books & Literature

ESSAY / Discourse around the Heathcliff casting

2 November 2025, 12:00 PM

Books & Literature

ESSAY / Everyone is migrating to Substack, and you should too

28 October 2025, 13:24 PM

Books & Literature

ESSAY / Leonard Cohen: Verses of mercy and turmoil

22 October 2025, 13:45 PM

Books & Literature

Sonnet of the riverbank: Remembering Al Mahmud, the poet

Some poets arrive like rain on parched soil—needing no defense, only recognition. Al Mahmud (1936–2019) was one of them. And yet, in the usual crookedness of history, we have found ourselves having to defend what should already have been canonised. There was a time—not long ago—when his name uns

29 August 2025, 19:49 PM