When old patriarchies wear new faces

I used to believe society moved in one direction—forward. We look at our grandmothers' era and think: "Thank goodness we've moved on." Recently, however, the rose-colored glasses I was wearing were shattered by a single statement. A prominent political leader in Bangladesh proposed that women who choose to stay at home should be honoured and rewarded by the state and that women's office hours should end by 5 PM. But the thought didn't feel like a step forward. Instead, it felt like a ghost from our collective past had just walked into the room, pulling with it the heavy chains of a century-old ideology.

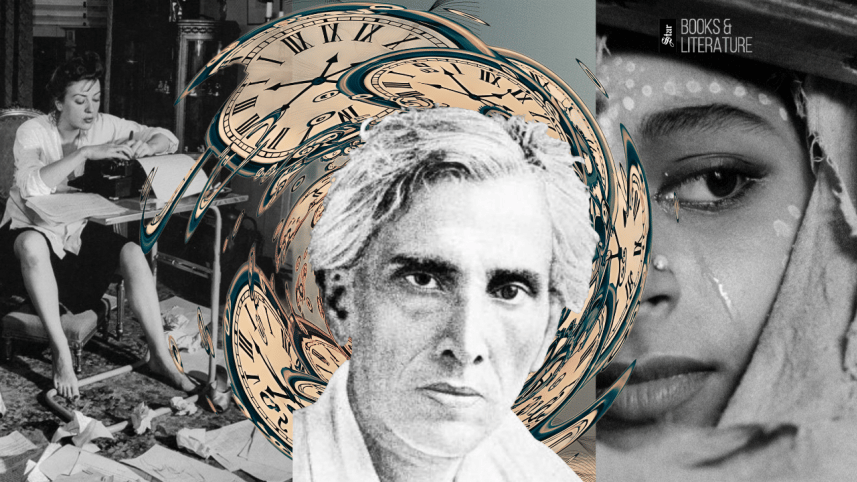

I was immediately transported back to the world of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, the Bengali writer whose works, a century later, can be read not as historical fiction but as a living commentary on the ongoing struggles Bangladeshi women still face.

This concept of state-sanctioned honour for domesticity substitutes a modern verse in an old song. One must pause and ask: what are we truly protecting here? Is it women's safety, or is it a particular social order that finds women's public participation threatening? The underlying architecture of the language used for the statement feels unmistakably like a cage. Perhaps gilded with tradition, but a cage nonetheless. This argument, embedded in the rhetoric of cultural preservation, is bizarrely similar to the societal pressures that kept Sarat Chandra's women confined within the 'andarmahal' for over a century. Even with their ambitions, intellect, and labour, they are invisible in the public sphere. It is the same patriarchal anxiety, now dressed in political language, that seeks to police women's ambition and strategically imply that a woman's worth is proportional to her domesticity.

To understand the deep-seated relevance of this modern debate, we must embark on a journey into the heart of Sarat Chandra's literature, where these battles first found voice. In Parineeta (1914), young Lolita's value is judged by her character, her "suitability" for marriage. Her love for Shekhor fails not from lack of feeling, but because of class and her uncle's debt to Shekhor's father. Lolita's story is a foundational battle against being defined by her economic circumstances and by a society that views her as a transactional object. The modern parallel is stark: today, a woman's character is still meticulously policed although the actors have changed. It is no longer just the potential in-laws, but relatives and colleagues who question the woman's character if she chooses to work late or, on the other side, her commitment if she leaves work early.

The proposal to financially honour homemakers creates a state-endorsed hierarchy. It implies a career woman is less honourable—her contribution is less valuable. This is Lolita's societal judgment, now presented as policy.

This policing grows more damaging in Charitraheen (1917). The widow Savitri is condemned for loving outside prescribed boundaries. The central victim of Charitraheen, Kiranmayi, is judged for seeking agency beyond her stifling marriage. Their truth is the first casualty in a society enforcing narrow codes. This kind of labelling today is subtler but equally potent. The career-focused woman is deemed neglectful or "too ambitious,' and is said to lack traditional values. The political statement mentioned before crystallises this: it doesn't only judge an action or a person's right to choose, but categorises the choice as acceptable or unacceptable by society's standards.

Ultimately, this is about a woman's right to her own legacy and labour. In Dotta (1918), Bijoya is a powerful, educated woman who manages her own estate. Yet, men constantly scheme to control her property and life through marriage. She fights to defend her mind, her property, her right to choose. This battle is painfully familiar. In today's world, female executives have to constantly prove their competence; the entrepreneurs face sceptical investors owing to their gender; the young professionals fight for equal opportunities and pay; and the list goes on. It is an enduring struggle to have a woman's professional territory recognised as rightfully their own.

In the face of these ongoing struggles, Sarat Chandra's heroines do not display victimhood but resilience. I see this same quiet strength in Bangladeshi women today. It doesn't always roar. Often, it whispers. The strength is in the woman who hears the proposal to honour only homemaking, feels its judgment, and still continues working—past 5 PM. It's in the student who guards her right to work besides her studies. It's in the mother navigating both home and work life—not because it's easy but because she claims the right to both worlds. Their resistance isn't always a loud protest. More often, it's the simple, revolutionary act of persisting—of living on their own terms. It's the spirit of Bijoya managing her estate, of Savitri holding fast to her love despite being labelled as characterless, and of Lolita fighting for her dignity.

The statement about the 5 PM curfew didn't surprise me; it clarified a crucial truth. The battles that Sarat Chandra chronicled—for a woman to exercise her right to her body, time, reputation, choices, and future—are far from over. They are not like old wives' tales. They live in the heart of every Bangladeshi woman who is told to be less, dream smaller, or retreat into a predefined role. The cages set by society have changed form, from physical walls to societal expectations, but the struggle for liberation remains. With this concluding note, in the quiet, stubborn, timeless resilience of women—in literature and life—we strive to keep writing a better, more equitable world for ourselves.

Nazmun Afrad Sheetol is an IR graduate and a contributor at The Daily Star. She can be reached at sheetolafrad@gmail.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments