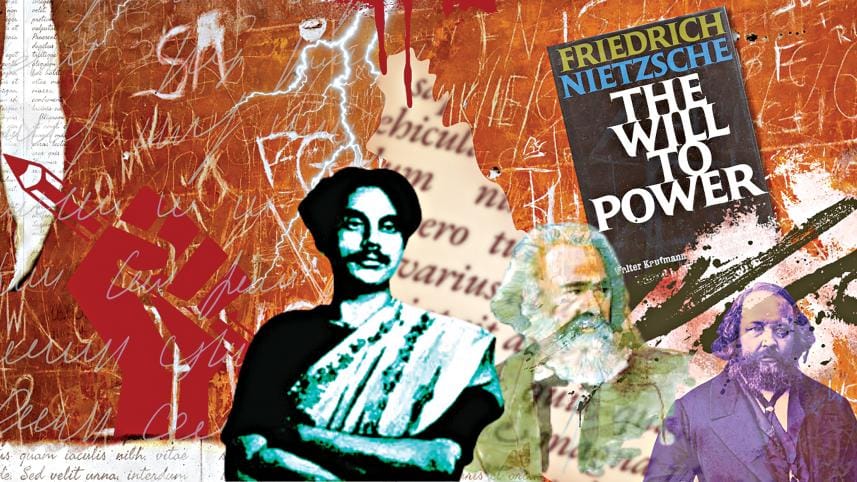

Symphonic overtures of Nietzsche-Marx-Bakunin in Nazrul’s ‘Bidrohi’

Mostofa Sarwar

Kazi Nazrul Islam’s Bangla poem “Bidrohi” (first published in January 1922), in Bijli magazine during British colonial rule, is more than just anti-imperialist literature—it is a striking philosophical rendition. The poem’s protagonist—the pervasive “I”—directly confronts political, social, religious, metaphysical, and economic authority, calling for an egalitarian society.

“Bidrohi” stands out in world literature as a synthesis of three philosophical streams: Nietzsche’s Übermensch, Marx’s class consciousness, and Bakunin’s anarchist vision. It is noteworthy that during the time of its composition, Nietzsche and Bakunin were not widely discussed among Bengali intellectuals, as Bangla translations were rare. A few English translations were known to some western-educated Bengali intellectuals. On the other hand, Marx had an exceptional presence in India, as the Communist Party of Bengal was formed in the early 1920s under the leadership of Muzaffar Ahmed, with whom Nazrul was closely associated. Therefore, while Marxist influence in “Bidrohi” is understandable, the philosophies of Nietzsche and Bakunin appear in Nazrul’s work through his own spontaneous creativity. Thus, the philosophical fervour of “Bidrohi” is Nazrul’s own—his original contribution. In this essay, I will analyse how “Bidrohi” functions as a meeting point of these three philosophies and presents a holistic vision of liberation and freedom that remains equally relevant today.

In Nietzsche’s The Will to Power (1901), “will to power” is described as the fundamental element of life. At its core lies the desire for mastery and self-transcendence. The idea of “self creation” is emphasised in The Gay Science (1882) and Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883). His call—“Become what you are”—is the process of reshaping oneself and overcoming all constraints.

From Nietzsche’s The Will to Power, we have an idea of his philosophy, which explains “Self Creation” as its existential goal. Nazrul’s “Bidrohi” firmly declares the spirit of self-affirmation. The rebel denounces all laws, traditions, customs, or dogma. Like Nietzsche’s Übermensch, the protagonist of “Bidrohi” declares his inalienable right to do anything his mind directs him to do. The poem’s “I” isn’t an imitation mimesis of Nietzsche’s—its representation is a unique force majeure, which is unfathomable even by the Almighty. The tone of the poem is all-out rebellion against any authority, power, mandates, culture, or historical memory. The hero of the poem trashes modesty, humility, and submission, and it is an absolute self-assertion of the highest form. He declares:

“Say, Valiant,

Say: High is my head!”

Even the highest peak of the Himalayas is seen bowing before the poet’s uplifted head:

“Looking at my head

Is cast down the great Himalayan peak!”

The indomitable ‘I’ is cruel, cursed, and arrogant without responsibility whatsoever. He presents himself as an uncontrollable and destructive force of nature:

“I am irresponsible, cruel and arrogant,

I am the king of the great upheaval,

I am cyclone, I am destruction,

I am the great fear, the curse of the universe.”

In the following lines, we see an extreme rebellion against traditional religious authority, the Almighty, and a determination to place himself and his own power at the highest point:

“Say, Valiant,

Say: Ripping apart the wide sky of the universe,

Leaving behind the moon, the sun, the planets

and the stars

Piercing the earth and the heavens,

Pushing through Almighty’s sacred seat

Have I risen,

I, the perennial wonder of mother-earth!”

Nazrul’s “Bidrohi” is not merely a political insurgent but a philosophical self-declaration—where Nietzsche’s self-creation becomes a universal metaphor.

Although the Rebel’s temperament is Nietzschean, the purpose of his rebellion is Marxist. It appears that the protagonist of this poem is announcing his own greatness, but, allegorically, he represents suffering humanity, i.e., the world’s proletariat. As the vanguard for the struggle of the oppressed, this poem’s ‘I’ wants to break all the laws imposed by the ruling elites. In the realm of antagonistic contradictions, the emancipation of India against imperial Britain demands rebellion, breaking the chain, and destroying the oppressive norms. I found this vivid class consciousness in “Bidrohi”.

“Weary of struggles, I, the great rebel,

Shall rest in quiet only when I find

The sky and the air free of the piteous groans of the oppressed.

Only when the battle fields are cleared of jingling bloody sabers.”

It may be noted that a few years after “Bidrohi” was published, Nazrul’s poems such as “Bhanger Gaan”, “Samyabadi”, “Sarbahara”, “Jinjir”, “Praloy Shikha”, and “Kulimajur” express direct Marxist themes—class consciousness, proletarian unity, and anti-exploitation revolt.

Between Nietzsche’s self-affirmation and Marx’s revolutionary goal stands Mikhail Bakunin’s anarchist philosophy. Bakunin, a “mad lover of freedom,” argued that true human liberation is possible only through rebellion against all external authority and coercion—state, capitalism, private property, and religion. Nazrul might not be aware of Bakunin’s anarchist philosophy because there is no Bangla translation. Still, his protagonist, Bidrohi, becomes an antagonist who issues a clarion call to destroy the socio-political structures, existing morality, and social constraints. It appears that the spectre of Bakunin possesses Nazrul. As Bakunin said, destruction is the precondition of creation.

“I have no mercy,

I grind all to pieces.

I am disorderly and lawless,

I trample under my feet all rules and discipline!”

As Bakunin said, destruction is the precondition of creation; Nazrul alludes to Durjati, the Hindu Lord Shiva, who destroys to create. We find that Nazrul independently reinvented anarchism as a philosophical tool for a noble dialectical process where destruction and creation complement each other. In fact, Nazrul elevated anarchism to a higher level of authenticity:

“I am Durjati, I am the sudden tempest of ultimate summer,

I am the rebel, the rebel-son of mother-earth!

Say, Valiant,

Ever high is my head!”

We can conclude that Nazrul’s poem “Bidrohi” is not only a breakthrough literary contribution in Bangla, but also that its philosophical underpinnings place the poet in the pantheon of the greatest creative geniuses of the world. The impact of this poem resonates in the rise of Gen Z’s rebellion across different countries.

All the quoted fragments of “Bidrohi” are from Professor Kabir Chowdhury’s translation that can be found on the Nazrul Institute website.

Dr Mostofa Sarwar is professor emeritus at the University of New Orleans, former visiting professor and adjunct faculty at the University of Pennsylvania, and former dean and former vice-chancellor of Delgado Community College. He can be reached at asarwar2001@yahoo.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments