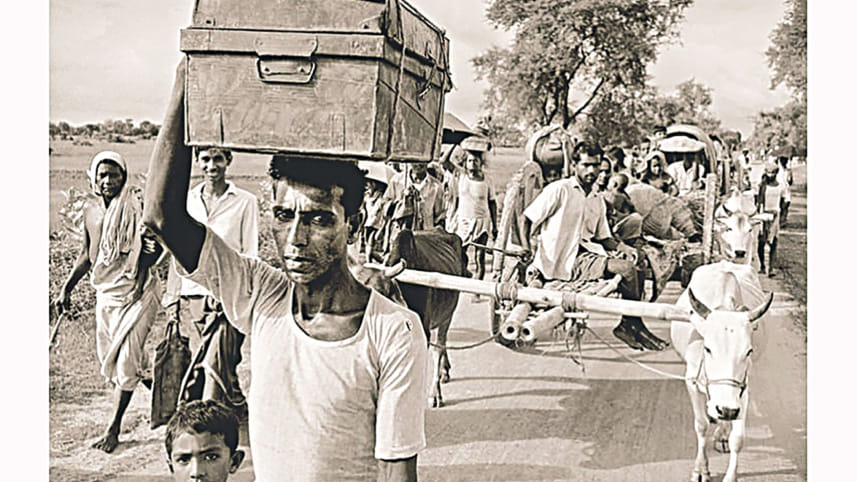

Retracing the 1971 exodus

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the victory that led to the birth of Bangladesh, attention should be paid to the devastating humanitarian crisis that unfolded during the nine-month war.

In addition, it is useful to understand this crisis in light of the ongoing Rohingya crisis, which unfolded more recently before our eyes.

The British had slit an undivided India with a 7,000 kilometre gash in August 1947. Pakistan may have been born along this artificially constructed border, but this led to deep wounds for many years to come.

Other than creating a refugee crisis during the partition of 1947, the British left the region in such a way that it generated subsequent refugee crises during the formation of Bangladesh, and in today's situation concerning Rohingya refugees.

First, let us analyse the case of Bangladesh. As a response to the economic and cultural discrimination from the 1950s onwards, Bengali Muslims from East Pakistan began demanding more regional autonomy from the authorities of West Pakistan, leading to an ethno-linguistic shift in their identity consciousness.

The Pakistani military began a sweeping crackdown in its eastern wing in 1971 with the intention of suppressing dissent and stunting Bengali nationalism permanently. Around ten million people were displaced into India's border states as a result.

In the beginning, the Indian government provided hospitality to the refugees and trained many Mukti Bahini freedom fighters from East Pakistan, who fought the Pakistani army for nine months.

Subsequently, the Indian army intervened militarily in East Pakistan, resulting in the Pakistani forces surrendering. India justified its military intervention with the argument that continual refugee flows into eastern and north-eastern India would create additional human suffering and further destabilise the region.

In spite of the USSR's backing, India's humanitarian intervention was not met with substantial support internationally.

A quick glance at the origins of the Rohingya crisis also point towards events surrounding the partition. In the time leading up to the partition of India, the Rohingya people of the adjacent Arakan province in colonial Burma hoped to join the future Muslim-majority province of East Pakistan, but were denied this opportunity.

The accelerated timeline and the poor transition of power from Britain to India and Pakistan may have prevented an agreement for the Rohingya population to be accepted in East Pakistan, and they remained part of Burma.

As Burma gained independence from Britain in 1948, Bamar Buddhist majority attitudes toward Rohingya Muslims slowly deteriorated. In 1978, the military junta in Burma carried out a crackdown in the Arakan province followed by the revocation of citizenship of the Rohingya community in 1982. Most Rohingyas have sought refuge in Bangladesh at different stages since then.

The partition process and the Two-Nation Theory both ignored the concerns of groups outside the center of power, including that of the Bengalis of East Pakistan and the Rohingyas of Arakan. More importantly, in both cases, successor states suppressed the political aspirations of those who later became refugees, despite external pressure against doing so.

By comparing the two crises, it illustrates how easy it is for governments and international organisations to frame refugee crises in a manner that imposes restrictions on their liabilities.

It was evident soon after the conflict began in East Pakistan that the Pakistani army had committed genocide in its eastern wing. Meanwhile, successive governments ignored the situation, which was the underlying cause of the refugee crisis, labelling it as a civil war and a matter of Pakistan's internal policy.

As with the Rohingya crisis today, if governments and international organisations had accepted state-sponsored "ethnic cleansing and possible genocide" were taking place, more meaningful action would have been required.

However, one of the main differences between the plight of the Bengalis of East Pakistan in 1971 and that of the Rohingyas, is the likelihood of external military intervention to improve their conditions.

Unlike the Indian military that unilaterally helped create Bangladesh, it does not appear that the Rohingyas are receiving any similar help, at least not anytime soon.

The international community's inaction and indifference may have also limited the likelihood of an international coalition engaging militarily.

Since all United Nations member states endorsed the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) in 2005, the absence of such outstanding interventions for the Rohingyas is now even more apparent.

The role of humanitarian relief organisations is another key difference between the two crises. In both cases, although the NGO community mobilised to highlight the sufferings of the refugee communities, the Rohingya crisis has tended to produce more criticism of Myanmar's government than what the East Pakistan crisis did of the Pakistan government's actions in 1971.

It is pertinent to note that for much of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, voluntary humanitarian action was characterised by the belief that humanitarian relief was a politically neutral practice, one where "strangers were saved" regardless of their allegiances.

The International Committee of the Red Cross, among others, remained relatively silent on the political matters causing the refugee crisis in 1971 -- an indifference which Oxfam and other radical non-government organisations (NGOs) increasingly questioned as the war continued.

NGOs responding to the Rohingya crisis, by contrast, have shown a much heightened willingness to engage in political discussions related to the refugee crisis, reflecting an overall strengthening of humanitarian NGOs as part of the international response to such crises.

Despite the fact that the two refugee crises in the eastern part of South Asia were precipitated by unlikey causes and events in the short term, their roots can be found in colonial British India and Burma, and in the subsequent partition in 1947.

British rule in the region and their exit in 1947 sparked a series of conflicts, including the conflict surrounding the formation of Bangladesh in 1971, and also indirectly the events in Arakan that led to the Rohingyas becoming stateless.

With independence in 1971, Bangladesh has slowly developed, and in many ways is outshining its bigger neighbours India and Pakistan. By contrast, the situations of many minorities in South Asia have deteriorated since 1947 and this is the case of the Rohingyas in particular, whose struggles do not seem to be ending anytime soon.

Dr Rudabeh Shahid is a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council's South Asia Center. This article is an adaptation of an earlier article written by the author and Samuel Jaffe in November 2019 for the online outlet, The Geopolitics.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments