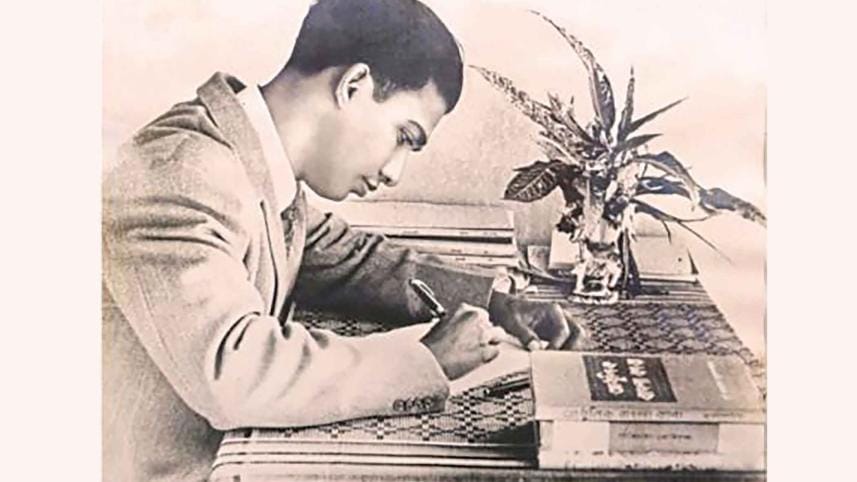

Rifle, Roti, Aurat: The first novel on the Liberation War

Dawn broke in Bangladesh. Shudipto is an early riser, and today was no exception. But it could have been. He didn't sleep much last night. There was the intermittent firing that rang out throughout the night. Along came the fear. Not of death—death no longer seemed frightening. He was afraid of living. Can a man live with such fire and bombardment? Thoughts like these crowded his mind. This place he was in now could have been another deterrent to his sleep. Sleep doesn't usually come easy to those visiting a new place, although in his case, it was the fire and shells and the accompanying fear that kept him awake. He could hardly focus on his new setting. Until now, that is. After waking up, his eyes wandered but couldn't find that familiar face of Number 23… those well-arranged book shelves, those tables and chairs, the looking glass. Nothing familiar greeted him at the break of a new dawn.

His mind veered to the present as he remembered Firoz. His friend Mohiuddin Firoz, in whose house he was now. A former poet, Firoz was once a well-circulated name thanks to his poems published in newspapers.

It was his first night in his friend's house. Shudipto, a professor at the University of Dhaka, reached at dawn on March 28, 1971 after traveling all night long. What of the preceding two nights? Shudipto found himself thinking about March 25 and 26. Those were no ordinary nights. Two nights with the length of two decades, as if offering a condensed history of the two decades of Pakistani rule, of the attitude of Pakistanis towards Bangladesh. Rule and exploit. Rule and exploit them in any way possible. If it becomes difficult to exploit, double down on ruling. Keep doubling down. If the rule of law doesn't work, then rule them with rifles, rule with cannons and machine guns. And, somehow, he survived two nightlong re-enactments of the dreadful rule of the past decades.

It now surprised him that he did. He could have been dead.

We all fail in our endeavours sometimes. Shudipto, for instance, couldn't be a CSP officer even if he wanted to. Or, could he be a rich person just by venturing into business? No. There are many who cannot even marry in their lives. But one thing that is certain to happen in all our lives is death. So, Shudipto was prompted to think, here was one thing that all can do—all can die. Without exception. It requires no effort really. You can eat all you want, do as you please. No need to break a mental sweat. The task will have been accomplished invariably one day. It's really that simple. It's your relatives and friends who will then be faced with a number of tasks. There will be the burial rituals, the prayers, the mourning, the tributes, the careful estimation of the money and property you leave behind. For some days afterwards, your loved ones will have nothing else to worry about—you'll have put them in a state of stupor. All these you'll have accomplished without so much as an effort on your part.

But no, all his ideas were proved wrong in his own case. Death was easy and within touching distance, yet Shudipto couldn't accomplish it. Why he didn't die, he doesn't know. Perhaps an easy death is not his fate. Many thousands of people easily did what Shudipto failed to do. He couldn't die. This made him wonder, perhaps dying is not so easy after all.

Not easy? Didn't Sofia die? Didn't he see how thousands of your brothers and friends died that day? Yes, he did. But he also saw that death can be difficult to achieve and he stands as living proof of that. If dying is hard, killing is even harder. Who will you kill? Can you kill an idea—a belief? The deep love and conviction with which those thousands of fallen souls embraced death couldn't be killed. They lived on.

Translated from Bangla by Badiuzzaman Bay.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments