Corruption and political instability: A threat to security?

“Under former President Moi, his Kalenjin tribesmen ate. Now it's our turn to eat," so said politicians and civil servants belonging to the then newly elected Kenyan president Kibaki's Kikuyu tribe in January 2003 to John Githongo, Minister for Governance and Ethics. The appointment of Githongo, former head of Transparency International Kenya was perceived to be an evidence of the new government's pledge to end the corrupt practices that had brought down the previous regime. In just two years, however, having compiled loads of evidences of high level corruption, Githongo found that he had taken too high a risk and hence left the country for exile.

Kenya is no exception. There are plenty of examples where state power is seized, with or without elections, declaring jihad against corruption and raising public expectations. New leaders condemn corruption of predecessors in the worst possible terms only to perform worse when they get the chance. Pretty soon the state structure including laws, policies and institutions are systematically converted into kleptocracy - in a manner that protects and promotes impunity for those in power to make profit, and fatten wealth and property disproportionately to their legitimate source of income. It becomes their “time to eat” as in the tribal culture. No wonder, one of our Ministers recently told this author: “charidike khai khai, thaki chaper modhye” (everyone is greedy all around, I'm always under pressure).

Bangladesh had the dubious distinction of being at the bottom of Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) during 2001-5. The ranking has improved since, though it remains among countries considered to be the worst affected by corruption. Bangladesh's position worsened in 2014 from 2013 – it scored 25 out of 100, two points lower, resulting in a slide of nine steps in the global ranking from 136 in 2014 to 145 in 2013. Bangladesh is the second worst performer in South Asia, better than only Afghanistan, which scored 12 and ranked 172, the third lowest position in the global list of 175 countries.

There are growing evidences, though not fully proven, that politically stable states are more successful in controlling corruption. Countries like Denmark, New Zealand, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Netherlands and Singapore which are known for stable governance have always been placed among top ten in the ranking of CPI.

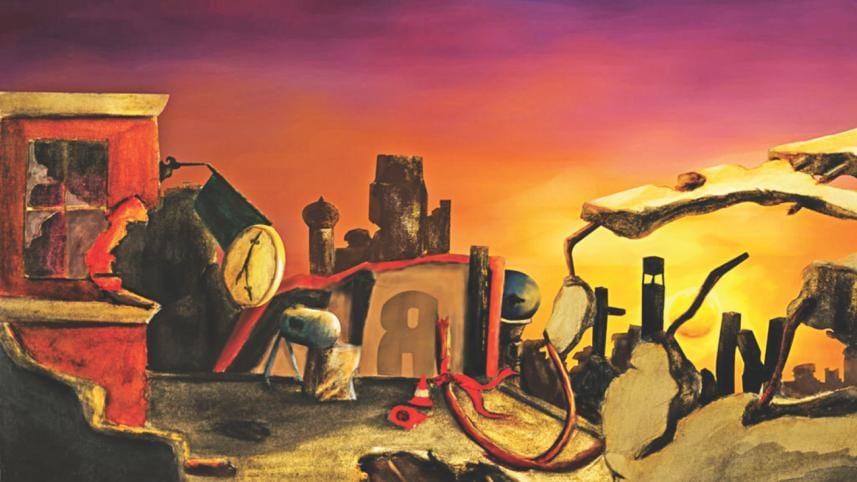

On the other hand, relevant data shows that countries affected by acute corruption tend to suffer from conflict and insecurity, while some are even on the verge of failure. The lower the countries are in the ranking of CPI, such as Somalia, Afghanistan, Sudan, Iraq, Libya, Yemen, Syria, the more politically unstable and institutionally weak they are. The political space in many such cases tends to be bedevilled by militancy, extremism or insurgency, posing considerable threats to national security. Given the possibility of such correlation, concern can be genuinely raised whether the on-going cauldron of political violence exposes Bangladesh to join the ranks of such countries.

Bangladesh has indeed made significant progress over the past couple of decades in terms of socio-economic growth including some key millennium development goals. With a record of sustaining a GDP growth rate of around 6 percent in the past two decades, the ratio of people below the poverty line has come down to 31.5 percent in 2010 from 56.6 percent in 1992. More recent data suggest that it may have dropped below 25 percent. Although quality remains a big concern, significant achievements have been observed in education and health. Bangladesh's score in Human Development Index has gone up from 0.382 in 1990 to 0.558 in 2013. With 17.2 of population in severe poverty (destitute) according to Multi-dimensional Poverty Index in 2014, Bangladesh was ahead of countries like Pakistan (20.7), India (28.5) and Nepal (19.9). In terms of Gender Equity Index of the same year Bangladesh, having scored 0.697, was better placed than Bhutan (0.637), India (0.647), Maldives (0.656), Nepal (0.647) and Pakistan (0.552).

While such performance is impressive, it also indicates the severity of lost opportunity due to corruption but for which we could have done far better. The cost of corruption has continued to grow with a particular bias against the common people with modest means. The National Household Survey 2012 conducted by Transparency International Bangladesh showed that 63.7percent of the surveyed households were victims of corruption in one or other selected sector of service delivery. Most important service delivery sectors affecting people's lives such as law enforcement, land administration, justice, health, education and local government, remain gravely affected by corruption.

In terms of implications of corruption measured by the amount of bribe, the situation has worsened compared to 2010, when cost of bribery in the surveyed sectors was estimated at 1.4 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or 8.7 percent the of annual national budget, which in 2012 rose to 2.4 percent of GDP and 13.4 percent of the annual budget. The survey also showed that while corruption affects everyone, the poorer sections of the society suffer more. Cost of petty corruption was estimated to be 4.8 percent of average annual household expenditure. More importantly, for households with the lowest range of annual expenditures the rate of loss was much higher at 5.5 percent compared to high spending households for whom it was 1.3 percent. The burden of corruption is clearly more on the poor.

On the other hand, an ever strengthening collusion of business with politics continues to damage the prospect of any firm and effective action against those responsible for grand scale corruptions in public procurements and infrastructure projects, share market collapse, loan default and scandals in the state-owned banks. Corruption in the export and import business in the form of fraudulent trade invoicing is considered to be widespread by which only a portion of traded value is settled by official channels while the remaining bulk is done by illegal channels of money transfer such as hundi. The result is not only large amounts of tax evasion, accounting for one of the lowest tax-GDP ratios of the world, but also outflow of assets worth billions of dollars. Bangladesh is a leading customer of Malaysian second home project, another popular conduit of illicit transfer. Deposits of Bangladeshis in Swiss banks were reported to have risen in 2013 by an exceptionally high rate of 62 percent.

On the other hand corruption also constitutes sources of insecurity as evidenced in the case of the Rana Plaza collapse resulting in deaths of more than 1200 innocent women and men. The building was allegedly constructed in an illegally occupied piece of land, violating laws, regulations and codes thanks to a collusion of corrupt officials with business facilitated by the powerful in both sides of the political spectrum. Corruption has also become a key factor of fatal violence and clashes between factions and sub-factions of the politically powerful to capture public contracts and illegally occupy land, water bodies, forests and market places. Corrupt transactions have become a major concern in a section of the law enforcement agencies ranging from alleged greftar banijya (arrests done for payment) during political agitations to gruesome murders as in cases of alleged involvement of RAB officials. Political affiliation becomes the most viable credential for securing permits to set up business enterprises in such sectors as banking, insurance and media houses. Power of corrupt money undermines rule of law and guarantees impunity.

The state structure is captured by those who benefit from corruption at the expense of those who would like to see it controlled. Politics is about winner takes all, and the game is played by use of force and resorting to violence. Staying in power or capturing it is the only option, and hence election only under such terms would ensure victory. Staying out of power is unacceptable not only because opportunity to amass wealth and income is lost but also for the mounting risk of harassment of multiple types including excesses by disproportionate use of force by politically influenced law enforcement agencies, fabricated cases, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings. The game is played at the expense of fundamental rights of the people including women, youth and even children with harsh brutality and heartlessness.

Newer and more ruthless forms and tools of violence are being applied to dehumanise politics and political space, causing severe threats to public interest, life, liberty, safety and security. The problem of political instability and violence cannot be resolved in isolation from the root cause of the zero-sum game, where the winner takes the term of office as a mandate to abuse power for wholesale wealth-seeking. Failure to cope with corruption can be as menacing a risk as threats to national security and potential collapse of the institutional structure of the state.

The writer is the Executive Director, Transparency International Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments