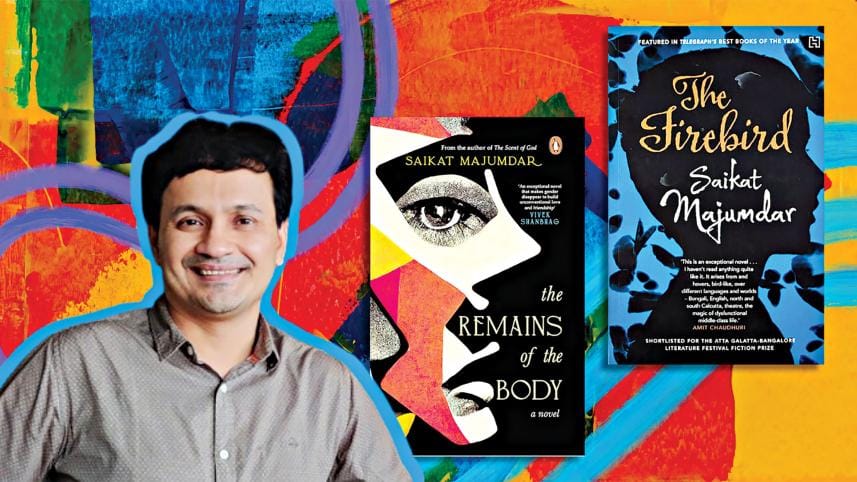

Unconventional realities and intense friendships

Saikat Majumdar writes with a sharp poignancy that arrows straight to the core of the heart. A Professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University, India, he has taught World Literature at Stanford University, and held fellowships at Wellesley College, Massachusetts, Stellenbosch Institute of Advanced Study, South Africa, and Institute of Advanced Study at the Central European University. He was also a Research Fellow in English at the University of the Free State in South Africa. He is the author of several fiction and nonfiction titles, including The Scent of God (Simon & Schuster, 2019) which was one of Times of India's 20 Most Talked About Indian Books of 2019, and a finalist for the Mathrubhumi Book of the Year Award 2020; and The Firebird (Hachette India, 2015), a finalist at the Bangalore Literature Festival Fiction Prize and one of Telegraph's Best Books of 2015. I spoke with him regarding his latest novel, The Remains of the Body (Penguin India, 2024).

The three protagonists of The Remains of the Body, Avik, Kaustav and Sunetra, are flawed, relatable individuals. What was the inspiration behind writing such complex characters?

I'm so glad you could connect with them. But why write fiction if one can't create characters that are lifelike? Flawed and relatable is a lovely way of putting it–I think they define the very essence of being human. The essence of this novel is the strange currents of friendship and sexuality between these three characters, who are very close to each other in both conventional and unconventional ways. These flows place a focus on characters that may not be there in a novel with a larger canvas where public events and histories play a larger role. Or such a focus there may coexist with other elements. This novel is the most spare and inward looking of all my novels, and also the slimmest, almost like a novella. All of these probably focused narrative energy on the complexity of characters.

Avik and Kaustav seem to blend into each other's personalities where they are one and the same but also very different. They are best friends with a very different outlook in life. What was the thought process behind centering the narrative around their relationship?

That's a striking observation about these two key characters. I'm very intrigued by intense friendships between people who are very different from each other–socially, psychologically, even in terms of political ideas, and vision and ambition in life. Perhaps these unlikely friendships only form in childhood or early youth. Particularly when you share memorable experiences such as attaining puberty, coming sexually of age–though that happens in radically different ways for the two of them. When you share such experiences, particularly from the vulnerable space of childhood and adolescence, you form a bond that stays no matter how differently you turn out later in life.

But for Kaustav, this intense proximity also makes him wonder why he has never been sexually attracted to Avik, particularly when he knows his body so intimately. Avik, who is not much of a thinker but more occupied with the material realities of life, is not aware of Kaustav's curiosity at all. But it remains an insistent question with Kaustav, who is almost disappointed that he does not feel that attraction for Avik who is precious to him in every other way. I guess I imagined Kaustav as a queer man trapped in a straight body. The complications really reach a crisis through Kaustav's relationship with Avik's wife, Sunetra as he cannot make sense whether his feelings for Sunetra is a straight man's attraction to a woman or a closeted queer man's feelings for his childhood friend through his wife, who has known that friend sexually.

There is love for Kolkata strewn across the novel yet this is a love felt from a distance. Kolkata appears to be a character in itself. There is also a distinct sense of place in the novel whether it is Kolkata, California, Toronto or Quebec. Why does place play such a significant role in the narrative?

That's a very moving reading of place. I think I'm very much known as a novelist of place and atmosphere, which is what The Firebird and The Scent of God sought to evoke from Kolkata and its surroundings. Interestingly, most of those novels were written from the US, whereas I wrote this novel set in North America while living in India and South Africa. Memory, I feel, is a natural editor for me–in its own mysterious and often-irrational ways, it tells me what is important and what is not. But I think the American and Canadian locations are important in this novel in a rather indirect way. These places are usually rather empty and even dull, though beautiful and high-functioning compared to Indian cities, which are chaotic, utterly mismanaged, but magnetic in their immersive, carnivalesque characters. I think by setting my novel in quieter–and perhaps less interesting spaces–I was able to look deeper in the inner lives of the characters, particularly the sexual and social tensions between them.

There's a scene where one character 'recognised her failures' in another. Do you believe that this phenomenon draws people closer or drives them apart? Why?

I think it is a powerful but unnerving moment when you recognise your own flaw or failure in another person. It can almost be a sense of disembodiment, kind of like looking at yourself from the outside. It's one of those things that I know partially from life, and partially through fictional imagination. One needs a high degree of self-awareness for this, as well as a deep understanding of the other person. It can bring you closer to that person, particularly if that flaw is something you value in yourself but which society considers a failure. This is the particular quality that Sunetra sees in both herself and Kaustav–her sense of being intellectually ambitious in ways that do not square well with the kind of material ambitions which most people in society, her own husband Avik included, actually prioritise. Their precarity in their professions make them both marginal characters, but this is because they refuse to take easy and safe careers. But Sunetra is possibly ready to stake something larger on this precarious ambition of scientific research–something as large as her marriage and family, unlike Kaustav, who is single.

Which character did you resonate with the most and why?

Kaustav holds the narrative consciousness in this novel, and in this sense, he is closest to the writer and the reader. But the character I really enjoyed crafting is Sunetra. I think I'm drawn to crafting strong, talented women who are either deeply flawed or full of intense self-doubt, which often arises due to their unusual intelligence. Such women appear in my previous novels too, but Sunetra felt special. Her physical appearance was important–I had the image of a small, frail, but sharply featured woman with glasses, someone who has a great scientific ambition and is also ready to be sexually adventurous in carefully chosen circumstances. Also, I imagined this woman to be trapped in a safe but mechanical career at the insistence of a materially successful but unimaginative husband who wanted to covertly, and sometimes not so covertly, control her career. That, I think, is a reality of many marriages, with men and women on either side.

In the Acknowledgements, you have stated that "Sometimes we write because there is a wound in our experience of life about which we can do nothing. Writing then becomes a cry of both pain and war." Can you elaborate on this?

I sometimes imagine this novel as shaped by the failed dream of pansexuality–sexual attraction felt by a person to all genders and sexualities. It seems to me unfair that for most human beings, sexual attraction is defined and set by gender. At some level, this feels claustrophobic, not only because it limits our sexual possibilities, but in fact all forms of human action and interaction, inasmuch as the erotic (far beyond the sexual) is a powerful driving force behind them. I fictionalised this by creating a character for whom this is not an intellectual question, but a deeply felt one that particularly haunts him with regard to the person he considers his closest–his childhood friend. To write fiction, I need a seed of reality, which sprouts into a forest before I know it.

Nabilah Khan is a writer based in Sydney, Australia.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments