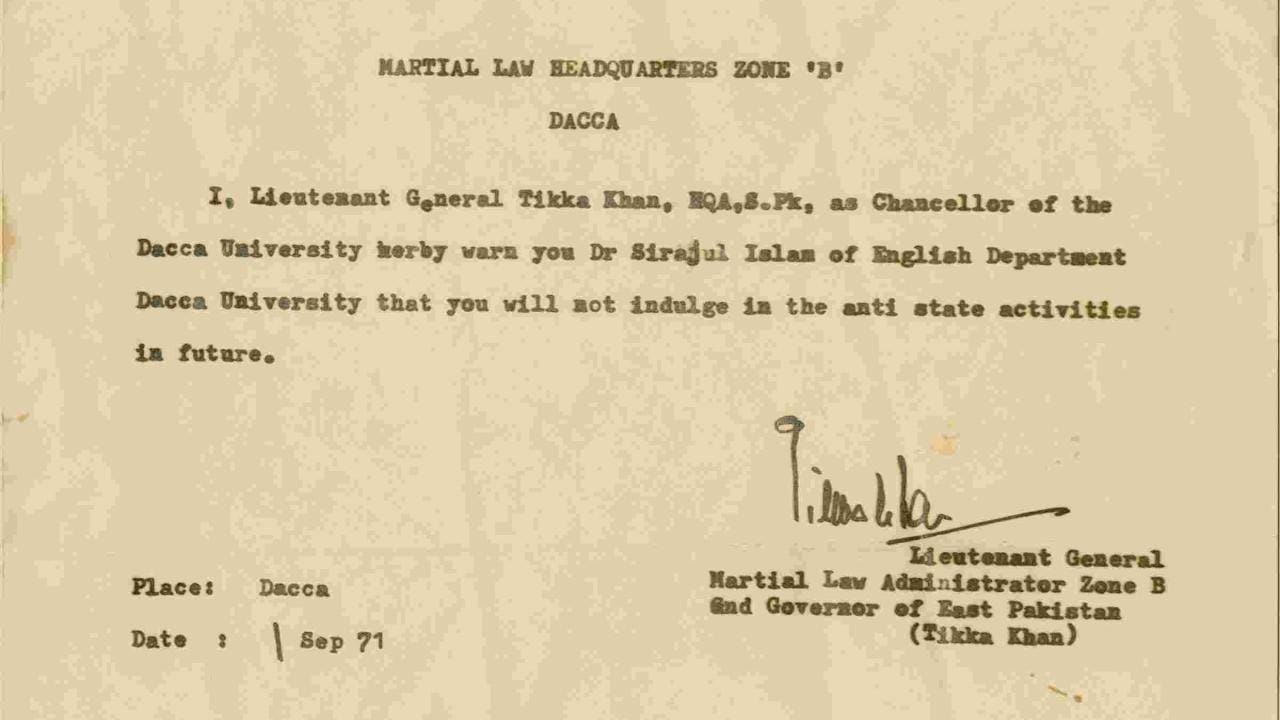

Tikka Khan’s letter of warning

In the first week of September 1971, as the military regime tightened its grip on a defiant Dhaka, a short, chilling letter arrived at the University of Dhaka. Issued under the seal of Martial Law Headquarters, Zone B, it bore the signature of Lieutenant General Tikka Khan—Governor of East Pakistan, Martial Law Administrator, and, by virtue of office, Chancellor of the university. Addressed to Dr Sirajul Islam of the English Department, it warned him against indulging in "anti-state activities." The language was terse, bureaucratic, and unmistakably threatening.

For Dr Serajul Islam Choudhury, the letter was both personal intimidation and a symbol of the regime's determination to silence intellectual resistance. Though dated 1 September, it was delivered a day later. He recalls how six teachers were named in total: Professor A.B.M. Habibullah of Islamic History; four scholars from the Bengali Department—Dr Muhammad Enamul Huq, Munier Chowdhury, Nilima Ibrahim, and Muhammad Moniruzzaman—and himself. Some were dismissed outright. Others faced punitive threats. Moniruzzaman, ironically punished for patriotic songs he had written for Pakistan but imbued with the spirit of Bengal, was handed a sentence of six months' imprisonment. The rest received warnings meant to terrify rather than prosecute.

The delivery of the letters, he remembers, felt grotesque—"like a prize distribution ceremony." One by one, the teachers walked into the office of the Acting Vice-Chancellor, who handed over each sealed envelope as though awarding a certificate. Behind this dark theatre lay a deeper fear: their files were now at the General Headquarters. As Tikka Khan prepared to hand over power to A.M. Malik later that month, he cleared these cases, leaving the academics exposed. "If Pakistan survived," Choudhury recalls, "we understood it would not be possible for us to keep our jobs; our lives would be endangered."

These fears were justified when, on 14 December, Al-Badr death squads began picking up intellectuals according to a list prepared by Major General Rao Farman Ali. Choudhury notes bleakly that his own name was on it, alongside those who would be killed. He survived only because the authorities did not have his address. Others were not so fortunate. Munier Chowdhury, whose home was clearly identified, was abducted and murdered. Professor Habibullah managed to flee the country just days before the killings.

Why were these academics targeted? Not because they were political activists, Choudhury insists. Their "crime" was intellectual independence: advocating nationalism, secularism, democracy, and socialism; defending university autonomy; protesting Ayub Khan's ordinances; writing in newspapers that supported the people's movement; and, most notably, organising a 23 March seminar at Bangla Academy on the future of a secular, democratic, and socialist Bangladesh. In a Pakistan where dissent had become treason, this was enough to attract the wrath of the military state.

Looking back, the letter stands as a stark artefact of a regime's paranoia—a document meant not merely to warn, but to break the collective spirit of the university. Instead, it became part of the long historical trail that reveals how Bangladesh's intellectuals chose courage over fear, and how the repression intended to silence them only strengthened the moral force of the liberation struggle.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments