The dawn of Islamic songs in Bengal

Abbasuddin Ahmed had taken part in singing Urdu qawwalis that described the richness of Islamic history and the love of Muslims for the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and Allah (SWT). He wished that one day he would be able to sing the praises of Allah (SWT) and His last Prophet in Bengali, his mother tongue. The names of the qawwals were Kallu Qawwal and Pearu Qawwal, whose songs impressed him deeply. There were no such songs in Bengali.

He thought of his favourite Kazida, meaning Kazi Nazrul Islam, the great poet.

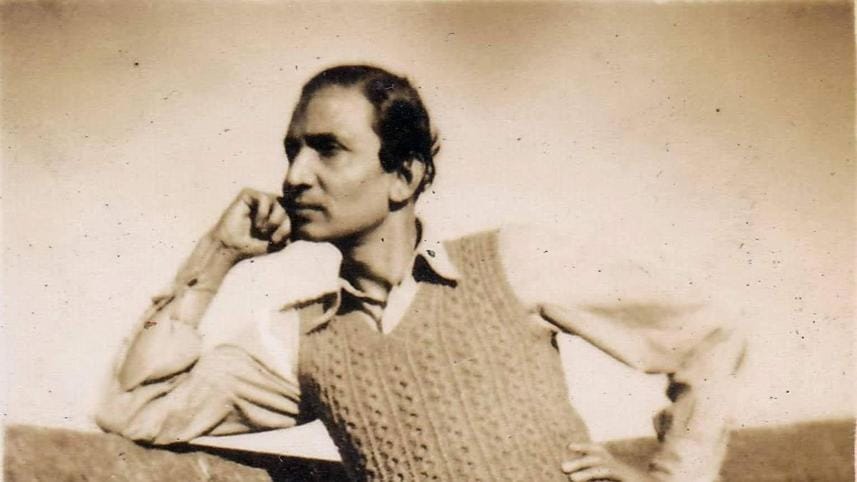

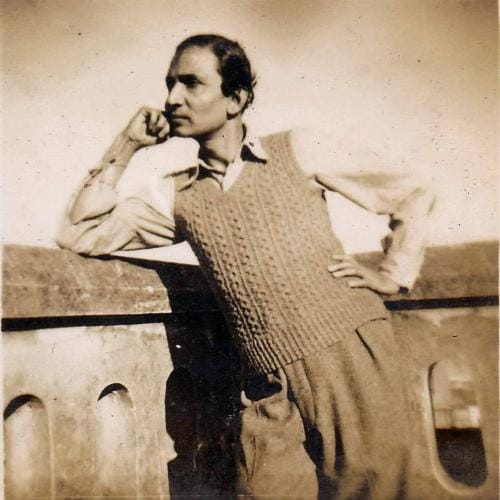

Abbasuddin hailed from Cooch Behar, which was a princely state in India. He was raised there and had come to Kolkata in pursuit of becoming a singer. Prior to that, he had met poet Kazi Nazrul Islam on two occasions. The first was when the poet was invited to Cooch Behar College as the chief guest. That was his first introduction to Kazi Nazrul Islam, around 1917. The poet heard his songs and showed much appreciation for his inherent talent.

A few months later, Abbasuddin went to visit Darjeeling. He used to visit Darjeeling every year during the change of seasons. There he heard that poet Kazi Nazrul Islam had arrived at an auditorium. He quietly entered and listened as the poet recited his famous poem The Rebel. Although Abbasuddin tried to remain incognito, he was spotted by someone who conveyed the message to Kazi Nazrul Islam. After completing his recitation, Nazrul Islam announced on the microphone, requesting Abbasuddin Ahmed to sing a song. Abbasuddin sang a Nepalese song, Aju re jau jau, bholi re jau jau.

A few years later, Abbasuddin gave up his studies and entered the world of music. He moved from Cooch Behar to Kolkata. He recorded two songs written by his friend Sailen Ray, which the HMV studios appreciated greatly. He met his Kazida again and started recording some of his most recent songs, such as Anek chhilo bolar. This was followed by several others—Gange jowar elo phire, Besuro beenay, and more. It was at this point that Abbasuddin met the qawwals, who asked him to sing some Urdu songs in chorus. Those were also recorded by Abbasuddin.

Kazi Nazrul Islam was then busy writing his Shyama Sangeet and Bhajans, all of which were in great demand. These songs carried both literary value and were celebrated for their unique tunes derived from Indian classical music.

Abbasuddin Ahmed felt the need for Islamic songs in Bengali. He proposed the idea to Kazi Nazrul Islam. Nazrul knew that the administrative officer of HMV studios might not agree to such a proposition. He sent Abbasuddin Ahmed to break the ice. The officer, named Bhagabati Babu, became extremely annoyed at the suggestion. He said, "I can't release such songs; there will be no customers for Islamic songs. In any case, Muslims are hardly interested in buying records." Abbasuddin was crestfallen but did not give up.

A week later, Abbasuddin Ahmed was entering the studio when he found Bhagabati Babu in a very good mood. He was chatting with a senior female artist, Ashcharjyamoyee, and his good humour was evident. Abbasuddin proposed again: "Can we just record a couple of Islamic songs? If they don't sell in the market, you need not record any more." This time, Bhagabati Babu realised Abbasuddin's resolve and gave in. He said, "OK, go ahead," and resumed his conversation with the female artist.

Abbasuddin rushed inside the studios, shouting with joy, "Kazida! Kazida! They've given permission to record Islamic songs!" Kazi Nazrul Islam was busy tutoring Indubala Devi, another famous female artist. He looked at Abbasuddin, then at Indubala. "Indu, I have some important work with Abbas. Today I shall beg leave from you and work with him." Indubala left.

Nazrul Islam called for Dasarath, the man Friday of the HMV studios. He was sent to the shops to get some betel leaf and several cups of tea. The genius was at work. In half an hour's time, he wrote the song O mon Ramzaner oi rozar sheshe elo khushir Eid. He asked Abbasuddin Ahmed to return at the same time the next day. The following day, he wrote another song in praise of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH): Islamer oi soudagor loye. Two songs were needed for one 33 rpm record. He set the tunes and taught them to Abbasuddin. The songs were recorded four days later.

There was a brightness in Kazi Nazrul Islam's face never seen before. He was overjoyed with this recording. He could hardly believe that the administrator at the HMV studios had agreed to the recording of Islamic songs. During those four days, Nazrul Islam had been impatient. He wrote the songs, and Abbasuddin did not have a chance to make a fair copy. He held the paper at eye level while Abbasuddin read from it and recorded the songs. They were accompanied by harmonium and tabla. The record was to be released two months later, during the Islamic festival of Eid (1932).

Before Eid, Abbasuddin was spending some time in the market, where he met another administrator, Bibhuti Babu, who worked for Senola Records (a recording company). He asked Abbasuddin to come to his shop. When Abbasuddin went there, Mr Bibhuti called a photographer and had a photo taken of Abbasuddin Ahmed. When he asked why, he did not get an answer.

Abbasuddin went to his native town in Cooch Behar and returned to Kolkata more than fifteen days after Eid. He was riding in the tram when he heard a young man singing O mon Ramzaner oi rozar sheshe to himself. After his work, he went to the Gorer Math; there too, some young men were singing this song in a group.

Abbasuddin remembered that the song was to be released during Eid. He went to meet Bibhuti Babu, who had printed hundreds of posters with that photograph. He gave seventy or so photographs to Abbasuddin and asked him to distribute them amongst his friends.

Abbasuddin rushed to meet Kazi Nazrul Islam. Nazrul Islam was playing chess with his friends. He was deeply absorbed in his game but abandoned it when he heard the voice of Abbasuddin. He hugged him close and exclaimed, "Your songs have been a great success." Abbasuddin felt reassured that the experiment had succeeded. The manager would now be convinced to record Islamic songs.

Nazrul Islam kept on writing, and Muslims loved every new song from the Abbasuddin–Nazrul duo. Nam Mohammad Bol, Tribhuboner Priyo Mohammad, Allah Amar Prabhu, and songs of Muharram (Marsia) filled the homes of Muslim buyers. Those who had never bought records earlier now thronged the record shops for more. The songs became immensely popular and were heard in every corner of undivided Bengal. Abbasuddin could only record two songs per month, so he requested other artists to lend their voices to Islamic songs.

Nazrul Islam kept on writing, and Muslims loved every new song from the Abbasuddin–Nazrul duo. Nam Mohammad Bol, Tribhuboner Priyo Mohammad, Allah Amar Prabhu, and songs of Muharram (Marsia) filled the homes of Muslim buyers. Those who had never bought records earlier now thronged the record shops for more.

Artists Takrim Ahmed and Abdul Latif recorded Islamic songs. Some Hindu artists changed their names to Islamic ones on the labels of their records. Ashchorjomoyee and Horimoti became Sakina Begum and Amina Begum. Chitta Roy became Delwar Hossain, and Dheeren Ray became Goni Miah. These songs formed the basis of Islamic emancipation and renaissance in undivided Bengal.

Abbasuddin received many letters from listeners requesting him to produce records with the Twin Company, whose products were more affordable. Abbasuddin sacrificed his own monetary interests and recorded his songs for the Twin Company. He hoped that less affluent Muslims could at least afford these records and have the opportunity to listen to them.

He approached Kazi Nazrul Islam again. Abbasuddin said to Nazrul, "Kazida, the Muslims of this land are now more drawn to music. You have been giving speeches to the young generation. You must write inspirational songs to further their self-determination and self-worth."

Nazrul Islam wrote several songs that spoke of emancipation, brotherhood, and unity of purpose — Dike Dike Punoh Joliya Uthiche, Shahidi Eidgahe Dekh Aj Jamayet Bhari, Dhormer Pothe Shoheed Jahara, to name a few. These songs were also appreciated by the Islamic community. They were played repeatedly in various congregational venues. When Muslims gathered, they sang these songs in chorus, their spirits lifted by the words.

From his early childhood, Kazi Nazrul Islam had knowledge of Arabic, Persian, and Urdu. It was a common practice in his family. Nazrul Islam's uncle, Bazle Karim, was well-versed in these languages and often wrote for the leto group. Leto is a folk group that sang songs based on mythological stories. The songs were written by experts. One day, Bazle Karim discovered that his nephew, Nazrul Islam, had completed some verses which he had left unfinished on his table. He recognised the genius of Kazi Nazrul Islam and gave him many more lessons. Nazrul became conversant with the stories of the Ramayan and Mahabharata. The leto songs were based on such stories, though occasionally Islamic philosophies were also incorporated into them.

Nazrul Islam started writing some of these songs, although he was not allowed to spend nights participating in performances. He became a famous writer in three villages near Churulia, where he was born in 1899.

In Churulia, there was a small mosque near his house. Sometimes the muazzin would be absent, and the local people called Nuru (the nickname given to Nazrul Islam) to recite the azaan. Nazrul Islam had a very musical voice, and his azaan sounded extremely sonorous. He would finish one azaan and wait eagerly for the next salat time to arrive. He often spent time with Islamic scholars who discussed both ritualistic and philosophical aspects of the faith. Nazrul Islam absorbed these discussions, and their influence became evident in his Islamic songs.

The simplicity of the Bangla language had a profound effect on Bengali Muslims. They eagerly awaited each new month for a fresh song written by Kazi Nazrul Islam.

Abbasuddin often urged Nazrul Islam to write more Islamic songs. Nazrul had many commitments and would be deeply absorbed in writing dramas. On one such occasion, Abbasuddin asked Nazrul Islam to write an Islamic song. He waited in Nazrul's living room while Nazrul worked with deep concentration behind the locked door of his study.

Abbasuddin knocked on the door. Nazrul rose from his seat and, with some annoyance, said to him, "Abbas, today is a bad day. I cannot write an Islamic song; I have to finish a drama I'm working on." Abbasuddin replied, "Kazida, I knocked for another reason. It is prayer time (Johr). Could you give me a prayer mat? I will pray and keep waiting." Nazrul opened his steel almirah and brought out a white towel. He gave it to Abbasuddin, who then offered his Johr prayers. He included the loud chanting of Allah's name, known as takbir. At the end of the prayers, when he went to return the towel to Kazi Nazrul Islam, he spotted a song written and lying on the cover of the harmonium. This song was titled He Namazi, amar ghore namaz poro aaj. It had been written while Abbasuddin was praying (Haque, Asadul, Islami Oitijjhe Nazrul Shongit, 2000).

Abbasuddin was deeply moved by this song. It remains a historic moment in which Nazrul Islam specially wrote a song for Abbasuddin. His prayers and earnestness in offering them touched the very core of Nazrul Islam's heart. He respected Abbasuddin and went on to write many more Islamic songs.

Though Muslims of undivided Bengal used to view music and dance as Hindu traditions and distanced themselves from them, they warmly embraced Abbasuddin's Islamic songs written by Kazi Nazrul Islam. From 1932 onwards, they became a celebrated duo. Every month, Muslims eagerly awaited the release of new Islamic songs written by Kazi Nazrul Islam. Abbasuddin sang seventy percent of the songs, while Nazrul Islam also encouraged other singers to lend their voices. Two Muslim singers, K. Mullick and Abdul Latif, lent their voices. As the demand for more songs grew, Nazrul Islam requested his non-Muslim singers to join in.

The Muslims of that time grabbed these records like hot cakes. In every Muslim home, the songs were played over and over again. The messages of Islam, which usually reached Muslims in the Arabic language, became closer and more tangible through their own Bangla tongue. The songs were passed down to the next generation, and every son and daughter knew Nazrul Islam's melodies by heart (Abbasuddin Ahmed, My Life in Melodies, 2014).

In 1942, Kazi Nazrul became unwell. He was later diagnosed with a version of Alzheimer's disease called Pyg's disease (Khan, I, Kobi Nojruler Oshusthota, 2005). He did not write any more after 1942. He and his family stayed back in West Bengal, India.

In 1947, India was partitioned. Pakistan was to be the homeland for Muslims. Abbasuddin Ahmed migrated to East Pakistan in 1947. He carried with him all his records made for HMV Studios and others. He taught his songs to his students—Sohrab Hossain, Bedaruddin Ahmed, Abdul Latif, and others. They, in turn, taught these Islamic songs to the next generation of music enthusiasts.

When television started in 1964, the Islamic songs of Kazi Nazrul Islam found a special place. The broadcasts would begin with Islamic songs, and songs of Eid-ul-Fitr and Eid-ul-Azha were telecast repeatedly.

The Eid-ul-Fitr song became almost a national anthem, recorded by several artists and broadcast every year on the eve of Eid. Through this song, Kazi Nazrul Islam held a lasting place in the hearts of Bengali Muslims. For every religious or solemn occasion, the Islamic hamds and naats of Kazi Nazrul Islam found their place in television broadcast schedules.

The daughter and son of Abbasuddin Ahmed, Ferdausi Rahman and Mustafa Zaman Abbasi, became renowned musicians and re-recorded all the Islamic songs of Abbasuddin Ahmed. This has created a continuity, reaching the new generation with the songs of Nazrul and unifying various political groups. None of the tunes of his Islamic songs were changed or distorted. Abbasuddin Ahmed brought with him his Islamic songs and helped preserve them forever.

In 1971, Bangladesh was born. The Islamic songs of Kazi Nazrul Islam, sung by Abbasuddin Ahmed, once again became the foundation for Muslims in independent Bangladesh.

Over time, private television channels emerged alongside the national broadcaster. Islamic programmes on these channels continued to feature the timeless songs of Kazi Nazrul Islam. Not only during Eid, but sehri and iftar programmes also began with Nazrul's songs. Likewise, in other broadcasts marking Islamic occasions such as Shab-e-Barat or Shab-e-Qadr, these songs were performed repeatedly. Over the years, they became the foundation of Islamic programming in Bangladesh—a tradition that continues vibrantly today.

Everyone, young and old, knows these songs by heart. The simple messages of Islam, beautifully expressed by Nazrul, have been memorised by millions of Muslims in their native tongue. Through these enduring melodies—especially his hamds and naats—Kazi Nazrul Islam continues to live in the hearts of Bangladeshis.

Nashid Kamal is an academic, Nazrul exponent, and translator.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments