The Narsingdi earthquake shook us—are we listening?

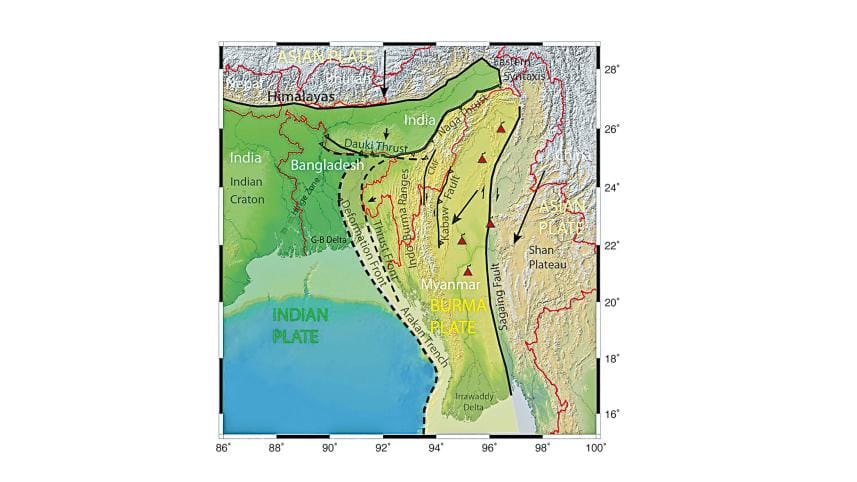

Bangladesh is a dynamic land where chars appear and disappear, rivers shift, and the coast grows and erodes over human lifetimes. The Earth is similarly dynamic, but over a much longer timescale. The rigid outer shell of our planet is divided into a number of rigid tectonic plates that slowly collide, separate, or slide past each other. Most earthquakes occur at the boundaries between the plates. The largest earthquakes happen where two plates move towards each other. These boundaries do not move smoothly; they get stuck, accumulate strain over hundreds to thousands of years, and then release that stored motion suddenly in a major earthquake. The collision of the Indian plate with Asia produced the Himalayas and Tibet, and generated the Nepal earthquake of 2015 and the Assam earthquake of 1950. On the eastern side of the Indian plate, the Indian Ocean subducts, or plunges, beneath Southeast Asia. The 2004 Sumatra earthquake and tsunami occurred along this boundary, rupturing a 1,200 km length. Another large earthquake ruptured a 500 km length of the Arakan coast of Myanmar up to Chittagong in 1762.

This plate boundary continues farther north into Bangladesh, but the main fault, the megathrust, is buried beneath the sediments of the Ganges–Brahmaputra Delta. The hills of Sylhet, Tripura, and the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) are the result of the deltaic sediments above the megathrust being folded up and faulted. The megathrust is a very broad and flat interface between the Indian and Burmese plates. It is completely buried by kilometres of sediments and is not visible at the surface.

We have been studying this plate boundary to try to understand its potential earthquake hazard. We have used many kinds of data to do this. One of the most vital is GNSS (GPS), with precision instruments that can measure movements to less than 1 mm/yr. These data show that the entire Indo-Burma Ranges are being squeezed, potentially building stress on the megathrust that will be released in a large earthquake. However, we do not know when the last one occurred in the Sylhet–Chittagong segment, or how frequently the megathrust ruptures. We cannot tell if it will be next year or not for another 1,000 years. Hopefully, there is sufficient time to prepare.

The other major tectonic boundary is between the Indian state of Meghalaya, or the Shillong Massif, and the Surma Basin. In Sylhet, Shillong is being thrust over Sylhet, uplifting the Massif and downbending the basin. The main fault here is known as the Dauki Fault. It is believed to mark the beginning of a shift southward of the Sikkim–Bhutan segment of the Himalayan plate boundary. This region was the source of the Great Indian Earthquake of 1897, estimated to be a Mw 8.0, although the latest investigations indicate that it was not the Dauki Fault that ruptured.

There are other faults in the region, such as those underlying the hills of Sylhet and the CHT, but they would only give rise to smaller earthquakes. The megathrust separating the Indian plate from the Burma microplate and the Dauki Fault remain the two structures capable of producing the largest and most damaging earthquakes.

The recent Mw 5.5 earthquake between Dhaka and Narsingdi was not on either of these two fault zones. It occurred within the Indian plate as it begins to bend as it enters the subduction zone. It neither significantly relieved the stress that is accumulating on the megathrust, nor is it likely to have made a potential megathrust earthquake more likely to occur. The earthquake magnitude scale is logarithmic; for each increase in magnitude, the earthquake releases 32 times more energy. Thus, a Mw 7.5 earthquake is 1,000 times more powerful than a Mw 5.5 event. While it was a minor earthquake compared to potential events on the megathrust or the Dauki Fault, it killed 10 people, injured scores more, and caused considerable damage. It is a reminder that even moderate shaking can be deadly when construction practices, as well as public awareness, are weak.

The recent earthquake should be considered a wake-up call to start making Bangladesh safer, if effective preparedness is undertaken. The typical construction of reinforced concrete columns and slab floors that is commonly built in Bangladesh generally performs quite poorly in large earthquakes. However, engineers know how to make buildings more resilient. For example, the addition of diagonal elements, shear walls, or other features can improve the safety of buildings. In 2011, while the unexpectedly large tsunami that occurred during the Tohoku, Japan Mw 9.0 earthquake caused immense devastation, no buildings collapsed from the earthquake itself. Earthquake engineering works. For an additional 5–10% in cost, a new building can be made much safer.

However, retrofitting existing buildings can be very expensive. Retrofitting should be reserved for absolutely critical buildings, such as hospitals and KPIs (Key Point Installations). Meanwhile, if people can afford to pay a little more and also follow building codes, new buildings can be more resilient and, over time, Dhaka can become safer for future generations. Bangladesh decreased deaths from cyclones from 300,000–500,000 in the 1970 Bhola cyclone to just 28 in Cyclone Amphan through investments made over the past 50 years. Making Bangladesh safer for earthquakes will similarly take decades or longer. Slowly, as buildings are replaced with safer structures and effective planning is undertaken to support people in the aftermath of an earthquake, Bangladesh will become more prepared to handle future disasters.

The recent earthquake also resulted in multiple buildings tilting. This highlights the risk of liquefaction throughout Bangladesh. The shaking from an earthquake can cause weak soils to temporarily lose strength. This is particularly a risk during the monsoon, when soils are saturated with water. The foundations of buildings must be deep enough for structures to remain secure, even if soils near the surface lose strength. There has been only limited research into near-surface effects, such as amplification of ground motion or liquefaction, in Bangladesh. Research into local variability in expected ground shaking throughout cities can be used to improve seismic zonation and adjust building requirements to local conditions.

Bangladesh is a country that faces a significant risk of a major earthquake, despite being categorised as a very low-to-low earthquake-prone country compared to its neighbours. Because the risk is low but highly uncertain, there is no clear answer to how much resource Bangladesh should allocate towards earthquake hazard reduction when there are so many other pressing problems requiring attention. However, any effort will pay off in the future by decreasing the impact of an earthquake.

This recent earthquake has raised public awareness of the hazard. That support should be capitalised on to improve emergency response and to plan land use and construction in a more risk-sensitive manner. Government officials need to demonstrate humility in the face of the complexities and capriciousness of nature while making realistic policies that the public can accept. The public needs education and greater awareness of earthquake hazards and the means to reduce them. It is important for everyone to understand what could happen in an earthquake and what to do if it happens, without panicking. Education can be disseminated in schools and community gatherings through short films, regular practice drills, and other forms of information. The government and the public must also be willing to bear the extra costs that reducing risk will entail.

Bangladesh should continue research in earthquake hazards and earthquake engineering, and support improved training for architects, engineers, planners, policymakers, and construction professionals. It should modify building codes and seismic zoning to take into account local variability in ground shaking and potential liquefaction. Bangladesh should do all it can to enforce building codes and incentivise safer new construction. It will be challenging to change societal norms and practices. Still, over time, these efforts can significantly reduce the impact of the next major earthquake. Earthquake risk cannot be eliminated, but robust risk management is both possible and achievable.

Michael S. Steckler, Lamont Research Professor and Associate Director of Marine and Polar Geophysics, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University.

S. Humayun Akhter, Former Professor, Department of Geology, Dhaka University, and Former Vice-Chancellor, Bangladesh Open University.

Md Mohimanul Islam, PhD, Visiting Research Associate, Department of Geological Sciences, University of Missouri.

Cecilia McHugh, Distinguished Professor, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Queens College, City University of New York.

Abdullah Al-Maruf, Professor, Department of Geography & Environmental Studies, Rajshahi University.

Md Hasnat Jaman, PhD student, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Columbia University, and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University.

Lin Shen, Postdoctoral Research Scientist, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments