Saving to death: How not to rescue wild animals

Across Bangladesh, both government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are frequently rescuing wild animals from urban settlements, roadsides, villages, markets, and even forests. Unfortunately, most of these animals are being released without proper care, treatment, physical fitness, or assessment of suitable habitats. There is no post-release monitoring either. The result is high post-release mortality, disease transmission, and ecological imbalance.

Bangladesh currently lacks an official rescue, rehabilitation, and release policy for wild animals. On a broader scale, and as a nation, the country has even failed to declare a national policy on wildlife management and conservation. Consequently, rescue and release activities are often ad hoc, uncoordinated, and undocumented. To ensure animal welfare, biodiversity conservation, and public safety, there is an urgent need for a national framework under the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and the Forest Department's Wildlife Wing.

This policy brief proposes an evidence-based, ethical, and practical approach to developing such a framework, aligned with the IUCN Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations (2013) and adapted to Bangladesh's realities.

BACKGROUND

Bangladesh's wild rescue rush: Between compassion and confusion

As Bangladesh races toward modernisation, a quiet crisis is unfolding in its forests and fields — one of displacement, confusion, and survival. Once known for its compassion toward animals, the nation is now grappling with the unintended consequences of rapid urban and agricultural expansion. This growth has led to severe deforestation, fragmented forests, and the genetic isolation of wildlife populations as monocultures of timber trees and crops replace natural habitats, depriving a wide array of species of their homes and livelihoods.

Historically, affection for animals in Bangladesh was largely limited to domesticated cats and dogs. Respect for wildlife, common in neighbouring countries like Nepal, Sri Lanka, and India, did not take strong root here. However, in recent years, the rescue and rehabilitation of wild animals have gained visibility — becoming a symbol of both progress and the problems that accompany it.

Shrinking forests, rising encounters

The boom in development has devoured landscapes that once sheltered wildlife. Bushes, reed beds, and grasslands have been replaced by concrete, shrimp farms, and monoculture plantations. Forests have fragmented under the combined pressures of land grabbing and commercial exploitation.

As a result, wild animals, desperate for food and space, have begun venturing into human territories, while humans continue to encroach deeper into animal habitats. This has led to more frequent human–animal conflicts, injuries, deaths, and emergency rescues.

A WAVE OF RESCUE — BUT AT WHAT COST?

Rescuing wild animals has become a public spectacle, fuelled by social media and viral content. Young people, NGOs, and government agencies compete to be seen as good samaritans. However, many rescues end in premature deaths or renewed suffering.

Animals are sometimes confiscated from illegal smugglers or private collectors, while others are retrieved from the homes of wealthy individuals who treat exotic creatures as status symbols. Yet, after the photo opportunities, most rescued animals are hastily released — often into unsuitable habitats, at the wrong time, and without medical checks or proper rehabilitation.

A May 2025 Mongabay investigation questioned the true outcomes for wild animals after their "rescue", and several national reports have highlighted the plight of these animals.

Mammals in peril

• Bengal Slow Loris — Often seized from traders in Dhaka or Sylhet, these nocturnal primates are released into random forests such as Bhawal or Lawachara without proper acclimatisation. Many die from stress or starvation.

• Common Palm Civet — Rescued from urban areas and released in broad daylight, these animals often become easy prey or roadkill.

• Fishing Cat — Found near shrimp farms in Khulna, Satkhira, and elsewhere, these cats are captured and released without consideration of territorial needs or prey availability.

• Binturong — Rare animals seized by law enforcers and released into forests lacking suitable fruit trees.

• Rhesus Macaque — Captured from urban temples and released in random reserves, they often clash with native troops or spread disease.

Birds without nests

• Oriental Pied Hornbill — Confiscated and released into tiny forest fragments without fruit trees.

• Hill Myna — Released in urban parks with no nesting cavities.

• Barn Owl — Set free in daylight, leaving them vulnerable to predators.

• Parakeets — Released far from their natural range, near rice fields.

• Black Kite — Freed from police stations before regaining flight ability.

Reptiles released to wrong realms

• Indian Rock Python — Released too close to human settlements, causing panic.

• Monocled Cobra — Handled by untrained personnel and released near highways.

• Monitor Lizards and Turtles — Dumped into ponds or canals without assessing water quality.

• Star Tortoises — Released in humid areas instead of dry scrublands, leading to fatal infections.

Hundreds of foreign and exotic species are being smuggled into the country, and the Wildlife Wing of the Forest Department is actively confiscating them.

THE WAY FORWARD

While the intent behind wildlife rescue is often noble, its execution reveals a lack of scientific planning. True rehabilitation requires trained personnel, health screenings, species-specific release protocols, and long-term monitoring — not viral videos or rushed releases.

WHY A POLICY IS NEEDED

Animal welfare

Many rescued animals are physically injured, stressed, or diseased. Immediate release without treatment violates ethical standards of animal care.

Birds kept in tiny cages by illegal bird vendors are being released almost instantly, causing serious threats to wild populations of birds and other animals, as such malnourished and untreated birds are traditionally known to carry diseases.

Ecological integrity

Releasing species into the wrong habitat (e.g., plains species in hilly forests and vice versa, or countryside animals into the Sundarbans) disrupts the local ecology and genetic integrity of wild populations. Ecologically and behaviourally, animals released into alien habitats will always remain physically weak and psychologically inferior to those already living and occupying established territories. Moreover, resident animals know where to find food and how to hide in the event of approaching danger.

Disease prevention

Without quarantine periods ranging from one to three months, zoonotic and epizootic diseases can spread to wild or domestic animals — and even to humans.

Accountability and data

Currently, there is no record of the number of animals rescued, their release locations, or their survival rates. Additionally, there is no system in place to track animals after release or to monitor their post-release conditions. This issue arises because current forest cadre service employees are primarily recruited to manage forests from a forestry perspective. Furthermore, even wildlife officers, who are employed for this purpose, cannot enter a forest without prior permission from a cadre service officer or a non-cadre service ranger. This is a significant flaw in national wildlife management and conservation efforts.

Alignment with international standards

The IUCN and many neighbouring countries (India, Sri Lanka, Thailand) have established clear reintroduction and release protocols. Bangladesh can adopt and localise these successfully.

CURRENT CHALLENGES AND INSTITUTIONAL GAPS

Bangladesh lacks a dedicated wildlife department responsible for managing land, water, air, and all biodiversity within a forested area. Currently, all land, water, and natural resources are managed by personnel recruited under the Forest Department's Wildlife Wing, where wildlife biologists have no role. These biologists are often regarded as 'imposters' within forestry operations.

There exists no central policy or Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for rescue, rehabilitation, and release.

Inadequate facilities: There are no designated rescue and rehabilitation centres in most divisions. A few that have been declared by the Forest Department exist in name only — established for formality, funding, or the utilisation of funds — without adequate workforce or facilities.

Lack of trained staff: Forestry staff and NGO volunteers often act without prior wildlife-handling knowledge, training, or veterinary guidance.

Limited veterinary support: Only a few veterinarians are skilled in wildlife treatment.

Overlapping roles: NGOs, local administrations, and the Forest Department's Wildlife Wing often perform overlapping or conflicting functions.

In 2024, a group of macaques rescued from a construction site in Dhaka was released near a residential park, where they began raiding households and were later re-captured — a cycle of suffering that proper rehabilitation could have avoided.

PROPOSED POLICY FRAMEWORK

A National Policy on the Rescue, Rehabilitation, and Release of Wild Animals should be adopted under the MoEFCC, with the following components:

1. National coordination mechanism

Establish a wildlife rescue and rehabilitation council (WRRC) under the Wildlife Wing of the Forest Department, with support from wildlife biologists working with national and internationally recognised organisations.

Include representatives from the MoEFCC, Forest Department Wildlife Wing, universities, NGOs, veterinarians, and law enforcement.

The council should oversee implementation, data collection, and inter-agency coordination.

2. Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

Drawing on IUCN guidelines and regional experience, with adaptations for Bangladesh's native species. Cover every stage: rescue → transport → food and feeding–housing care → veterinary care → quarantine → rehabilitation → release → post-release monitoring.

3. Regional rescue and rehabilitation centres

Establish at least one centre per division, linked to major protected areas.

Facilities should include:

• A wildlife rescue manager with a degree and experience in wildlife management.

• Proper housing facilities for rescued megafauna, birds, and reptiles to be built under the guidance of wildlife, zoo, or safari management experts. These must have a continuous supply of water and electricity and be connected by road networks.

• Facilities for food storage, preparation, and serving, equipped with proper vehicles.

• At least one wild animal rescue ambulance, created by converting a large pick-up truck, with first aid and emergency treatment and care facilities. The government might request donor agencies to provide one or two such wild animal rescue ambulances.

• Veterinary treatment units and isolation cages to be built following international benchmarking standards.

• Soft-release enclosures for adaptation to be built in suitable locations.

• All rescued animals must be recorded in a database capable of storing species name, sex, age, and condition, as well as their history in the facilities and eventual fate.

• Record-keeping and SIM- and satellite-based tagging systems are necessary.

• All rescued animals must have a microchip inserted into their bodies.

4. Authorised release sites

• Designate species-specific, ecologically appropriate release areas.

• Prohibit release into urban, village homesteads, or agricultural landscapes.

• Conduct pre-release habitat assessments and post-release monitoring.

5. Capacity building and training

Develop and conduct regular training modules for Wildlife Wing staff, NGOs, zookeepers, and veterinarians. Include safe capture, handling, species identification, and welfare assessment. Partner with universities and veterinary schools for technical expertise.

6. Data management and reporting

Create a national wildlife rescue database accessible to the MoEFCC, Forest Department, universities with wildlife departments, and registered NGOs.

Track each case with GPS coordinates, photos, treatment details, and survival outcomes.

7. Public awareness and engagement

Educate the public on responsible rescue practices through posters, television, and social media. Disseminate guidelines on what to do when encountering injured or displaced wildlife. Promote citizen reporting via mobile apps or hotline numbers.

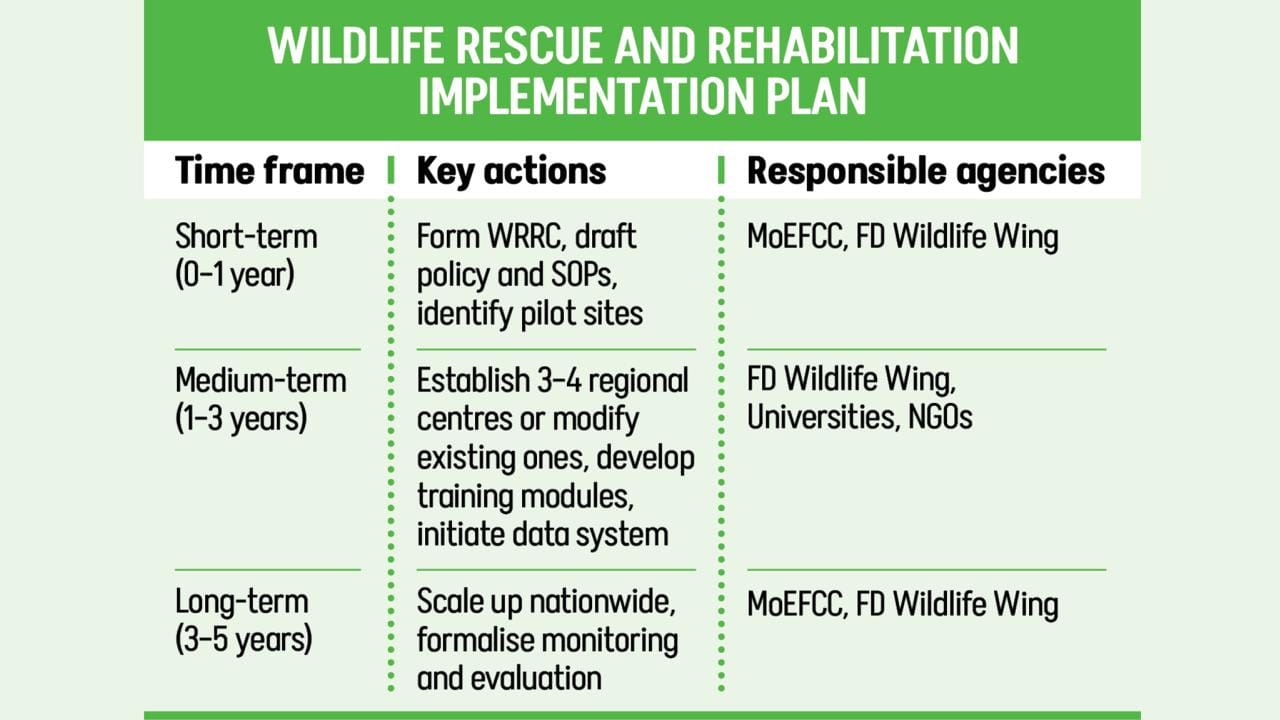

RECOMMENDATIONS AND WAY FORWARD

• The MoEFCC should initiate the drafting and adoption of a national wildlife rescue and release policy.

• Pilot rehabilitation centres should begin in Dhaka, Chattogram, Khulna, Rajshahi, and Sylhet regions.

• Mandatory veterinary oversight must be required before any release.

• Database and transparency mechanisms should be instituted for accountability.

• Encourage cross-border learning with India, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

• Integrate the initiative within the broader Wildlife Conservation Master Plan under the Forest Department's Wildlife Wing.

Bangladesh has the expertise and dedication — what is needed now is an organised, ethical, and scientifically guided policy framework to protect its wildlife from good intentions that go wrong.

Dr Reza Khan is a wildlife biologist and conservationist with over four decades of experience in wildlife research, zoo management, and biodiversity conservation in Bangladesh and the United Arab Emirates. He has worked extensively in wildlife rescue, sanctuary management, and community-based conservation initiatives.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments