Ressurect humanist values

The Daily Star's annual review is usually a projection of expectations and challenges. As Bangladesh lives through a non-participated election, preceded by brutal violence and denial of all norms of human dignity, we cannot do more than raise concerns for 2014.

It is not only because the state has become hostage to a brutal power struggle, or that “democratic” elections have been no more than a road to autocracy. Or that impunity of state forces as well as of politically motivated/instigated violence has shaped the insecurity of our daily lives. It is more so because we seem to have lost our way to democratic tolerance and civil engagement.

The goal of our struggle for independence and of our earlier struggles was the making of a democratic state, embracing a diversity of cultures; we did not want to be dominated by a narrow elite that claimed to represent the majority.

So we believed…

We took up the challenge to build a democratic state and a secular society where diverse citizens' voices would be heard, where we would not be tied down by medieval dogmas. Our struggles did away with military rule, and replaced them with civilian representatives. Election followed election and citizens lined up in large numbers at the polls.

We did so because we wanted our choices to be reflected...

Come election time we braved a degree of violence and compulsion, but often found that money power and muscle power prevailed over popular choice in election contests, that influence peddling rather than rights would decide the shape of the state, that business interests would ride over citizens' concerns.

Nationalism was the driving force in 1971. It united people around a common demand for justice. We looked for a new beginning – economic, political and social.

But we tripped along the way…

We failed to draw strength from the diversity of cultures and beliefs. Instead nationalism was narrowed by exclusion of class, ethnicity, religion, caste and gender. We failed to nurture processes that would be non-discriminatory and inclusive. The divide between the rich and the poor, between one religious group and another, the neglect of ethnic communities, the divisions of gender have raised walls of intolerance.

The goal of our struggles was the making of a secular society. Bangladesh was to be a home for inter communal harmony, tolerance and respect for diversity.

But we have divided ourselves by religion and ethnicity …

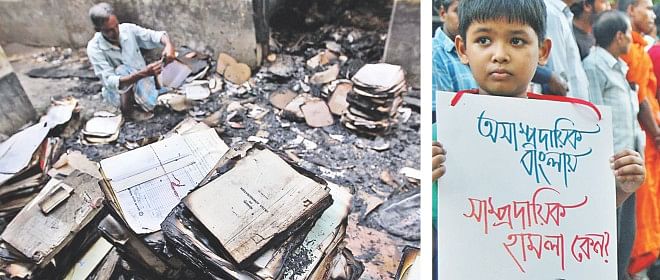

Minority communities are generally vulnerable to power plays. Religious minorities, particularly live in apprehension and fear as elections approach, or when events in India are used as a pretext for sectarian violence in Bangladesh. In 1986, 1991 and even more brutally in 2014 Hindu communities have paid the price for daring to belong. According to newspaper sources in 2014, Hindu temples, deities, homes and businesses were set on fire, demolished and damaged in many places across the country. The first attacks came after a judgment by the International Crimes Tribunal in February/ March 2013, the second after the announcement of election schedule in November. Since we had been forewarned by similar attacks since 2012 in Dinajpur, Satkhira and Ramu, we should have been better prepared. It was no surprise that once again in 2014, Hindu voters were left to their own devices, with little legal or administrative support. Also missing were initiatives by the elected representatives and other political leaders who had been voted in by these very citizens.

In 2001 too, elections had prompted gang attacks on similar targets. The High Court gave directions for an independent enquiry in response to a public interest litigation, but its directions were ignored. If an enquiry was undertaken, it was never made public, and no effective preventive strategy was devised by government agencies. Impunity for discrimination and sectarian violence has muddied our goal for a tolerant and inclusive society.

Nationalism should not impel us to denigrate or demonise the other, or to claim superiority for one tradition over another. We cannot live in separate compartments; we can and must learn to live together in peace.

Even as I write this, newspaper headlines scream at us: Woman raped and killed in Khagrachari; the irony is that military camps may guard our territorial borders but they cannot protect women. Another news story in the same paper reads “She chooses death after divorced for dowry, raped and videoed”. Can no law put an end to inhuman customary practices or are they a means for capital accumulation?

How do we reconcile advances made by Bangladesh towards the MDGs with such brutal violence? Yes, state initiatives have created spaces for women's education, for their employment, and yes maternal mortality figures have radically declined and their life expectation has gone up. But must its price be paid in domestic violence, or violence at work?

Intolerance and violence cannot promise justice nor is it the way towards an open, democratic society. Let us challenge impunity and reaffirm our humanist values. We need to actively nurture a culture of mutual respect, tolerance and peace.

The author is Chairperson, Ain O Salish Kendra.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments