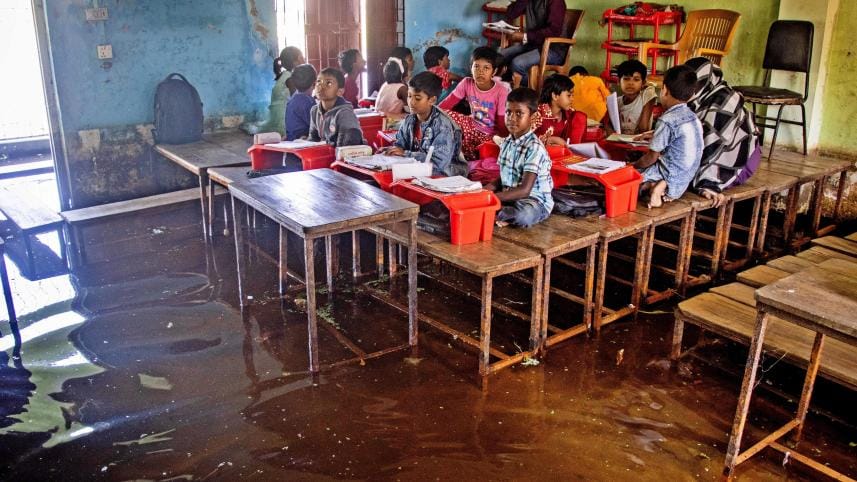

A picture that lays bare the decay of our education system

On November 19, we published a picture of a classroom of a government primary school in Dumuria, Khulna. All the benches, made of steel to ensure durability, have been huddled together to create an elevated base on which about 15 primary-level students are squatting and studying with the teacher at the back. Why are the students sitting on an elevated platform instead of on the benches made for them? Because the floor is under ankle-deep water. How long has this situation persisted? Five months. Why? Because the nearby Shoalmari River is choked with siltation. When will these students get back to their normal schools? Given our history of handling river siltation, it is likely to take a long time. So, for the foreseeable future, this is how these students will experience their school life, unless, of course, they fall victim to waterborne diseases. In that case, can we pause for a moment to consider what health facilities are available for them?

One has to admire the commitment of the teachers, and especially of the students and their parents, to continue school in such adverse circumstances. The tragedy is that this "adversity" has been normalised for the last five months and practically for every monsoon season.

Our reporter from Khulna says that students from at least 22 villages are commuting to school on boats every day and attending classes, as seen in the photo. During the coming winter chill, many may have to wade through waist-deep water to reach their classes, exposing themselves to cold, fever, skin infection, and other diseases.

How will these primary school students perform in the final primary school examination to be held from December 1? The same concern applies for the students of secondary schools in Dumuria and other upazilas where exams have already started, as well as for the students scheduled to take the SSC test examination. According to local officials, 45 educational institutions in Dumuria alone, including 18 secondary schools and one college, are currently affected by waterlogging.

Yet the project to clear the siltation is stuck in a bureaucratic maze, and no one knows how long locals will have to suffer before it is resolved. What is certain, however, is that primary and secondary school students of the upazila will have lost some invaluable time and opportunities in their academic life.

What we have pointed out above is the situation of schools in one upazila. What is the state of schools in general in terms of their physical condition? According to Department of Primary Education officials, as of July 2024, out of 1.07 lakh primary educational institutions in the country, 49,656 were new, in good condition, and functional, while 18,271 school buildings were old, 16,998 repairable, 11,613 in dilapidated conditions, 5,252 risky, 3,307 abandoned, and 1,348 non-usable.

If we put together the schools identified as dilapidated, risky, abandoned, and non-usable (the difference between the last two categories is not clear), then we have around 22,000 schools that are not safe for our children. If we add the schools that become flooded and non-functional due to seasonal heavy rain, river siltation, storms, and cyclones, then we end up with a far larger number of schools unable to carry out their function as planned. This affects several lakh students every year.

Add to the above the revelation of the latest Multiple Indicator Cluster survey—covering 63,000 households countrywide, and conducted by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) and Unicef—that only 44 percent of students complete secondary level education, while 56 percent, or more than half, do not.

If an education system leads to the failure of more than half of the student body, then what sort of system is it? Yes, there are many socio-economic realities, such as child marriage, which is cited as one of the main reasons for this situation. But then, what are the related ministries, like women and children's affairs, doing about it? If there were accountability in our system, we wouldn't be here.

According to the latest figures, the positions of 34,106 primary school head teachers and 24,536 assistant teachers are vacant. Not that recruiting them all would solve many of the problems, as there would definitely have been political influence and corruption in teacher recruitment. It is a reality we have allowed for decades. But that said, why should the relevant ministry sit on these appointments? Again, no accountability.

The question we want to raise is why, after 54 years of independence, our primary and secondary education is still in such a miserable state. Why are we continuing to produce mediocre students? We have seen improvement in enrolment, but we have failed to properly develop students' ability to learn and absorb knowledge, and cultivate a curious mind. Shouldn't the July charter, especially since it was heralded by student activists, have addressed this particular issue as it directly affects the future of students?

After independence, we have had a total of eight education commissions: i) Qudrat-e-Khuda Education Commission of 1972; ii) Interim Education Policy under Kazi Zafar Ahmad, 1978; ii) Mazid Khan Education Commission of 1983; iv) Mofiz Uddin Education Commission of 1988; v) Shamsul Haque Education Commission, 1997; vi) MA Bari Education Commission, 2002; vii) Mohammad Moniruzzaman Mia Education Commission, 2003; and viii) Education Policy Formulation Committee headed by Kabir Chowdhury in 2009. In addition, there were additional committees and policy-formulating bodies during the last 54 years.

The point to note is that the above education commissions worked under different regimes, both political and military. Yet hardly any of their recommendations were implemented; not even a few substantive ones saw the light of day despite so much work and resources expended.

To us, this failure is demonstrative of how frivolously we have treated education in general, and primary and secondary education in particular, for the half-century of our existence as a sovereign country.

Political division has cost us tremendously in most aspects of our lives. But its most damaging impact has been in the education sector. Very few, if any, countries have seen the formation of eight education commissions in 54 years of their life. If the commissions were building on the gains of the previous ones, it could have been a different story. Over the years, our education system has never received the consistent support that it needed. As with everything else, partisanship played havoc.

In our view, the education commissions, like most other things, were seen through political lenses and never as institutional ones because no attempt was made to ensure they appeared non-partisan and neutral. When forming a new commission, the governments of the day did not take the opposition into confidence and allow a consensus to emerge so that, with a change of government, the commission's relevance would continue. The attitude of the new regime was never to implement the ideas but to reverse them. And so, recommendations got buried each time with the change of regime. It was politics that determined the views for education reforms, never the needs of our children or those of the nation.

All through the last 54 years, there was also an absence of a strong and independent implementation authority. Educational reforms are fundamentally long-term. They cannot be subject to frequent changes tied to election results. An implementation authority established on a non-partisan basis with the participation of the political opposition is what Bangladesh needed—but it's something that we never even tried for.

Political division has cost us tremendously in most aspects of our lives. But its most damaging impact has been in the education sector. Very few, if any, countries have seen the formation of eight education commissions in 54 years of their life. If the commissions were building on the gains of the previous ones, it could have been a different story. Over the years, our education system has never received the consistent support that it needed. As with everything else, partisanship played havoc.

And of course, there were powerful, well-entrenched groups who resisted any change. Teachers' bodies were among the most consistent lobbies that resisted any form of change, as it would have required new skills and new qualifications. Bureaucracy was devoid of any commitment, mostly for the same reasons. At the moment, we have two ministries looking after education, namely the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education and the Ministry of Education. Neither of them has the necessary expertise, motivation, or infrastructure to push for innovation and modernisation.

Take the case of the use of technology in modernising our education. Which department will take the lead in this area? Any change or innovation to penetrate into the maze of bureaucracy has to come in the form of a "project" to be funded by a donor or the World Bank, etc. The biggest shortcoming of a project is that it is time-bound and once that time expires, it stands abandoned unless there is a "new" project with additional resources. To their credit, donors, especially the WB, have shown flexibility here and funded education projects that had multiple phases. Even in such cases—with continuity assured—we lacked the vision, commitment and motivation to vigorously move towards our goals. One reason for it was the frequent transfer of bureaucratic leadership, many of whom, well aware of their limited tenure, made the best use of it often through frequent foreign trips, expensive and high-end transport, and future consultancies, if they were on the verge of retirement.

Why do we need an external donor for something that is a long-term need and most essential for us? Whatever it takes, education, health, agriculture, and food, when necessary, should be funded by us and adequately so. Shortage of funding has been a chronic failure on our part. We are among the lowest funders for education in the world as well as in the South Asian region, even lower than Nepal, whose resource constraints are far more severe than ours.

A lot of hue and cry was made as to why Prof Yunus's government did not set up a special commission for education. What we should have done instead—and we had a rare opportunity (and perhaps still do) in that aspect—was to examine the recommendations of the past eight education commissions, pick up the most relevant and doable ones, make them part of our "consensus dialogue", and get us that convergent policy directive that we so badly need. Or, as this government has done in some other cases, it could have issued an ordinance on the most urgent, relevant, and widely acceptable education reforms.

At the root of the success of all modern nations lies education, which must be periodically modernised to make citizens efficient, innovative, contemporary, and prosperous. This allows a nation to take full advantage of innovations that science, technology, social sciences, and modern administrative and business practices offer. Not reforming education is like holding a nation static and preventing it from advancing. The Golden Era of Islam, especially the Abbasid period (eighth to 13th century), the Meji period in Japan (1868-1912), and the modern period in China—to cite some relevant examples—should guide us well as to the role of education in moving a civilisation forward.

Mahfuz Anam is the editor and publisher of The Daily Star.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments