Lessons from Mamdani’s magic: Put voters at the centre of our politics

Forget other issues and challenges, Zohran Mamdani's election as mayor of New York City proves the supremacy of the "will" of voters. He was opposed by every organised power imaginable in New York. But he was supported by "people's power," which is the only power democracy is supposed to recognise. If the official election machinery is uninfluenced, then voters can defeat all other powers in a democracy. President Trump was publicly opposed to him, so were the Republican Party and even Democratic Party high-ups (Clinton supported Mamdani's opponent), and the elite class in general, who poured in billions to oppose Mamdani, yet the voters won. Democracy prevailed. Most importantly, it broke the sense of powerlessness of the poor, the inferiority complex of the middle class, and the psychological barrier of the disempowered—that the elite can never be defeated. Nothing could have boosted the US's image as a democracy more than this.

This election has greatly strengthened our belief in elections, the power of unity among voters, and a new faith in public wisdom. A majority of New Yorkers shattered everything that the current political trend in the US stands for. Of course, Mamdani was a great speaker, and he ran a superb campaign. But the crux of it was that he sensed the public pulse and articulated it effectively, so that the voters developed trust in him. All of this would have amounted to nothing if voters did not have the courage, determination, and energy to express their views by casting their votes in record numbers.

Our election may not be similar to Mamdani's in terms of upsetting the ruling class, but it is a similar moment for us in terms of returning to democracy. Once again, we hope we are at the doorstep of a lively parliament where government and ruling party can be held accountable, where bureaucracy will once again not be the "masters" but the "public servants," as they were recruited to be, and police will enforce the law and not be "above the law" unlike before, when they have enjoyed perpetual impunity regardless of what they did. In my view, one word encompasses everything that we expect and hope from this election: establishing accountability. Our election—hopefully a free and fair one—is coming to us after 17 long years, and for that many years, and also before it, we did not have accountability.

So much time, energy and resources have been spent in bringing various political parties together, taking them through an organised process of discussion, and trying to bring out their collective thoughts—all to build political consensus on fundamental issues. While that was very good indeed, no effort was made to gauge the views and expectations of the voters. Voters are never at the core of our election process; in fact, they are hardly given any importance.

There is much to learn from the NYC mayoral election, even if some may say the two contexts are very different, one being in the US and the other in Bangladesh. The differences are ornamental; the similarity, in terms of holding power to account, is fundamental. And the lesson is how to touch the hearts and minds of voters, gain their trust, energise them to work for you. There were over 50,000 volunteers, mostly young, working for Mamdani. The voters believed in him so deeply that they were willing to take all the risks that conventional wisdom would have warned them against, but they did not shy away.

Will Bangladeshi voters have that chance? The challenge is not only to appeal to them but to empower them, to give them the confidence that they matter. Mamdani explained the strategy of his campaign: while politicians usually go to voters, telling them about their plans and how implementing them would benefit the public, he, instead, went and asked what they wanted. "All said they wanted New York City to become affordable for them. So, we built our campaign around how to bring down the cost of living in the city," said Mamdani. In our case, do our politicians ever ask voters what they need or want? Will they do so this time?

After eight months of the National Consensus Commission's (NCC) dialogue, we expected a much stronger consensus among all political parties to hold a free and fair election. We did not expect them to put conditions and couple them with threats. How can anybody say that if our demands are not accepted, then there cannot be any election? What sort of respect for voters does that show? It is disappointing to see that Sheikh Hasina may have left, but our basic political culture of imposing partisan agenda on the people has not changed. To the best of our knowledge, there has not been a single attempt by any political party to conduct any opinion survey to find out what our people want.

So much time, energy and resources have been spent in bringing various political parties together, taking them through an organised process of discussion, and trying to bring out their collective thoughts—all to build political consensus on fundamental issues. While that was very good indeed, no effort was made to gauge the views and expectations of the voters. Voters are never at the core of our election process; in fact, they are hardly given any importance.

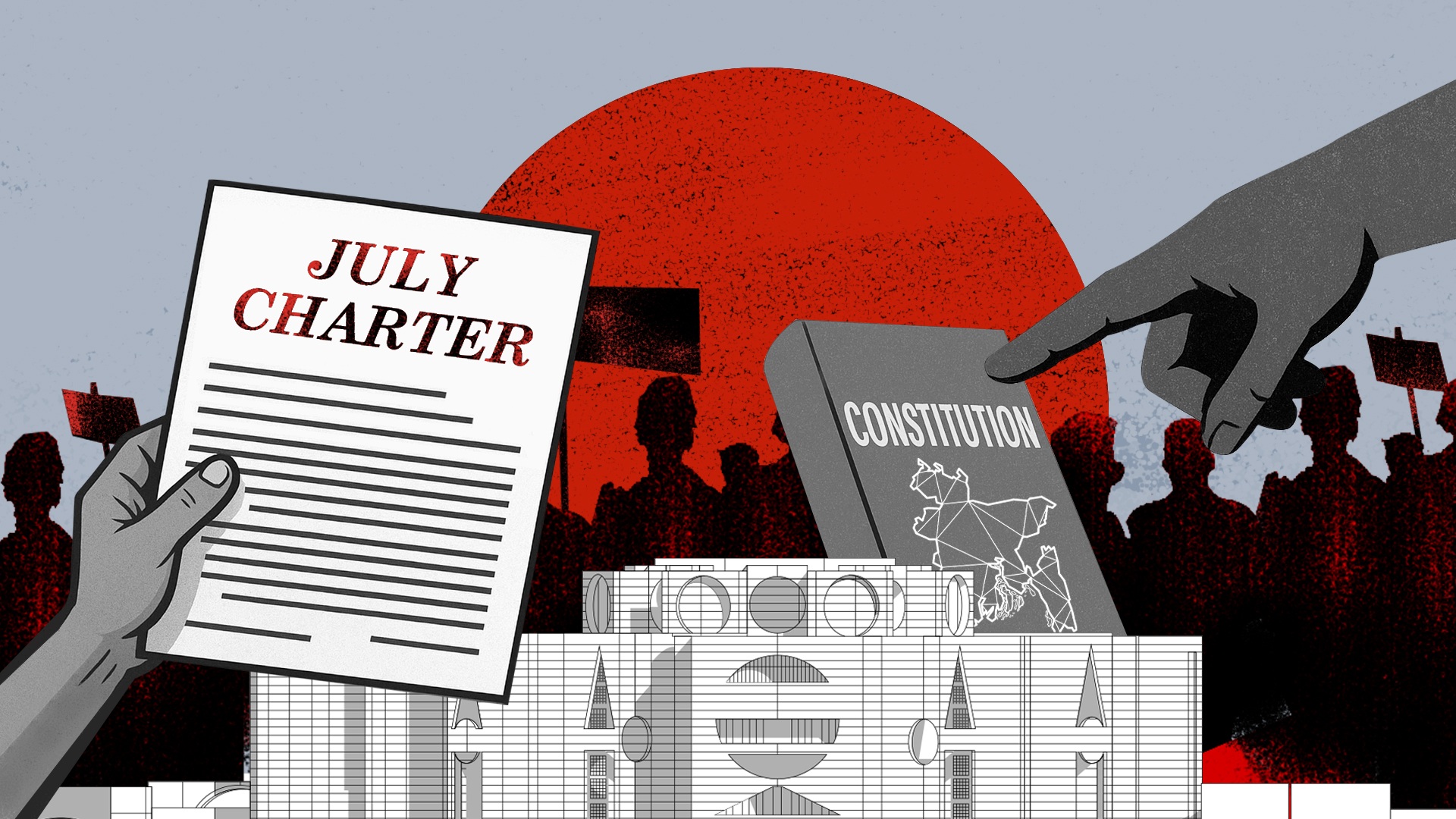

Take, for example, how much money and time we have spent on finalising the July National Charter, but how little effort has been made to make the general people aware of its contents. Originally, there were 84 recommendations. Now the plan is to focus on 48 of them that deal with reforming the constitution and hold a referendum on those. Don't the public have a right to know what these recommendations are, what they mean, what their implications are, and how they may affect their lives? It is our view that voters below a certain level of education, such as farmers, day-labourers, rickshaw-pullers, street hawkers, vendors, small shop owners, many factory workers, domestic help, etc—numbering in the crores—would most likely know very little about what the July National Charter contains. With so little public knowledge, how can we conduct a referendum on such a crucial and complex document that deals with constitutional reforms? Would that be ethically and morally correct? Would such a referendum give us any authentic view of the public position on this document?

Whatever may be the impediments, the most important task before the whole nation—and one that we must pledge to implement with all our sincerity and energy—is to hold the highly anticipated national election that the country desperately needs, within the time frame announced by the chief adviser.

The term "interim government" is self-explanatory. Whatever its time frame, it is a transitory authority. Bangladesh's global relations, though greatly benefitted by Prof Yunus's personal popularity and prestige, cannot assume normalcy till an elected government is in place. Media report shows that domestic private investment sank to a five-year low in the current fiscal year and there is a general sense of uncertainty and a lack of confidence among investors due to the absence of an elected government. Local entrepreneurs are reluctant to invest their money without a clear view of the coming government. So, elections must be held on time, and any impediment placed in its path can serve no other purpose than to hurt our national interest.

However, there are many challenges that need to be overcome before holding a free and fair election. There is the lack of trust between political parties. Each believes that whatever is being promised before the election will not be honoured after victory. It is for this simple reason that NCP and Jamaat are insisting on a referendum, although its practicality and legality have raised many questions. The reason is simple: lack of trust in BNP's promises. It is true for all other parties as well.

Then there is the history of abuse of the administrative machinery, which creates an unbalanced level playing field. All political parties know how the state machinery—especially the police and bureaucracy—is used to influence elections. That knowledge is fuelling the present suspicion about the neutrality of these public institutions.

The fear of political violence is also a reality that we cannot set aside. Already, disturbing signs of intra-party clashes are becoming worrisome. According to Ain o Salish Kendra data, this year, between January and September, 323 incidents of political violence took place across the country and more than half of them were within the big parties. How the rivalries at the grassroots level will play out as the election date nears is a constant source of anxiety in holding a free and fair election.

The sad fact is that, at this final stage, we have no consensus yet on the future direction of the nation. After eight months of discussions, the government was forced to ask the political parties to come to some final common position within one week for the electoral process to move forward. We hope the appeal is honoured.

As we understand, the issue for Jamaat and NCP is proportional representation at the Upper House. We think it is a reasonable demand, which will make the functioning of the Upper House more effective. After all, the latter cannot be made a rubber stamp of the Lower House. It will be, if BNP's wish prevails. We think BNP should see the merit of the alternative.

Jamaat and NCP, on the other hand, should accept BNP's suggestion that coalition members be allowed to use the symbol of the umbrella party. This may not be the best option. However, dissenting parties should accept it as a compromise. Though a gazette notification has already been issued, there's enough time for it to be amended if a political consensus can be reached.

As for the date of the referendum, the solution seems to already exist: do it on the same day as the national polls, as suggested by BNP. Though we strongly feel that holding the referendum as referred to above will not be fair to the voters, who do not know much about its contents, still, to remove the impediments for holding the election, NCP and Jamaat should accept the proposal. The logistics of holding it on a separate day are humongous and expensive. It is like doubling the expense, and the logistics will be impossible to manage.

Thus, we see a high possibility of a convergence of views among the three main parties.

Concluding, as we began, with the inspirational example of Mamdani's election in New York City—show the voters the respect they deserve and give them a chance to have their wishes fulfilled. Bring them to the centre of chalking out the future of Bangladesh. Let us end the culture of imposing our own wishes on voters.

Our plea is that all political parties, especially the three prominent ones, must put aside their differences and place national interest above everything else, and join hands to hold the election in February 2026. We need to stop going in circles and move forward.

Mahfuz Anam is the editor and publisher of The Daily Star.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments