Why survival in Dhaka feels accidental

Dhaka has always been a city of contradictions—of ambition and neglect, progress and peril, pride and decay. In recent times, the contradictions have turned fatal. The same projects that symbolise our march towards modernity now routinely remind us how fragile and often expendable human life has become. From the death of Abul Kalam Azad under a falling metro rail component to the fires that devour factories and warehouses, from the plane crash that reduced classrooms to rubble to the toxic air that quietly robs us of years, Dhaka seems determined to prove that survival here is not deliberate but a coincidence.

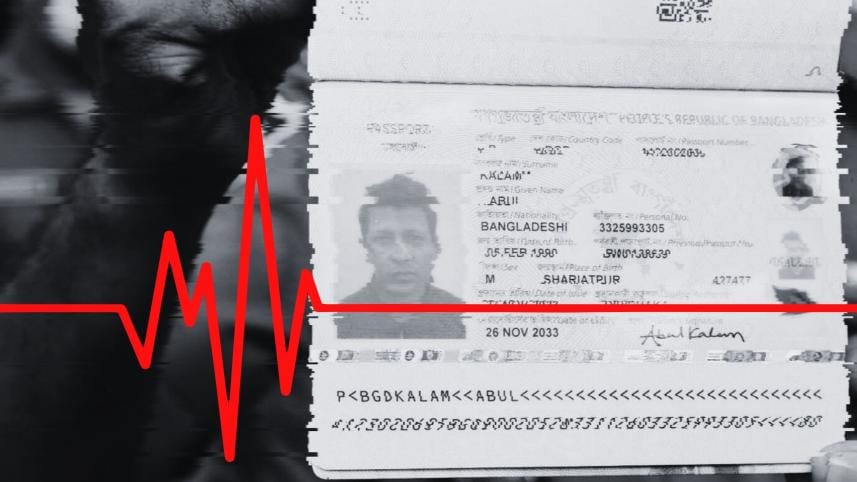

Abul Kalam Azad, a 35-year-old father of two, was sipping tea at a roadside stall—an ordinary act on an ordinary day—when a bearing pad from the overhead metro rail suddenly hit his head, killing him instantly. The irony could not have been sharper. A project built to elevate the lives of Dhaka's citizens literally came crashing down upon one. That small, seemingly insignificant part—a bearing pad meant to absorb shock between the pillars and the rail—became a symbol of a much larger shock: how recklessness and negligence have been normalised in this city.

The metro rail, built at a staggering cost of Tk 1,500 crore per kilometre—among the highest in Asia—was meant to be Dhaka's modern marvel. Instead, it has now become a cautionary tale of misplaced priorities and poor oversight. Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (Buet) engineers had reported substandard bearing pads as early as 2020. A similar incident in 2024 saw a bearing pad fall off another section, after which a committee was formed and recommendations made, which, for whatever reasons, were not enough to prevent the fatal accident.

A compensation of Tk 5 lakh was swiftly announced, as if a human life could be itemised and closed like a project file. A metro rail that could take more than 50 years to recover its costs could not guarantee safety for one of those who paid for it with their taxes—and now, with his life.

The structural fragility of Dhaka is not without moral frailty. Within a week, two major fires broke out in the city—at Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport's cargo village and Mirpur's Rupnagar area. Thirty-seven fire units battled the airport blaze as flights were diverted to Chattogram and Kolkata. The Mirpur fire killed at least 17 people in a garment factory after an adjacent illegal chemical warehouse exploded.

We have seen this before, again and again. Fires that start with a spark and end with commissions of inquiry. In 2024 alone, Bangladesh witnessed 26,659 fire incidents—an average of 73 fires every day—killing 140 people and injuring more than 340. The Fire Service and Civil Defence recorded property losses of Tk 447 crore, though how one measures the loss of dignity or livelihood remains unclear.

The causes are familiar: illegal chemical storage, faulty wiring, congested roads, locked exits, and weak enforcement. The solutions are also familiar: task forces, mobile courts, and promises of reform. The repetition itself has become a tragedy. When fires occur with such regularity that they no longer shock us. Emergency becomes routine.

In the Mirpur blaze, hydrogen sulphide gas reached 149 parts per million—a concentration deemed "immediately lethal." Even then, crowds gathered at the site—families searching for missing loved ones, onlookers recording footage, and journalists narrating the spectacle. The scene captured both the human cost of failure and the national habit of treating disasters as daily news rather than turning points.

What makes these fires unforgivable is that they are preventable. Most originate from the same few causes, and most could be stopped with basic enforcement and planning. Yet the city continues to grow upward and outward with reckless speed, as if height itself were proof of progress.

If fire exposed our lack of safety, the plane crash at Milestone School in Uttara laid bare our lack of preparedness. When a military training jet plunged into the school compound, killing and injuring children, the tragedy revealed just how unprepared our emergency response remains. There was a shortage of ambulances at the scene, no field hospital, and coordination was chaotic, as if emergency care were a lottery rather than a right.

Burn victims were rushed through choked streets to the few hospitals with any capacity, while infection risks soared in overcrowded wards. In the absence of institutional response, citizens improvised. Volunteers carried stretchers; doctors extended shifts. Yet good intentions cannot substitute for good governance.

Disasters in Bangladesh expose not just the fragility of systems but the hierarchy of concern. Each new tragedy triggers outrage, condolences, and pledges of reform. But once the headlines fade, the next tragedy quietly queues for its turn. We have learned to live with institutional dysfunction as though it were a natural phenomenon—like rain or traffic.

And then the omnipresent air itself becomes the enemy. According to the Air Quality Life Index (AQLI), Bangladeshis are losing 5.5 years of life expectancy due to air pollution. Dhaka residents could live seven years longer if particulate matter levels were reduced to World Health Organization (WHO) standards.

In 2021, over 19,000 Bangladeshi children under five died from pollution-related illnesses, according to UNICEF. The sources are well known: brick kilns, old diesel vehicles, unregulated construction, and industrial waste. Brick kilns alone contribute nearly 60 percent of Dhaka's air pollution.

The government has declared certain zones "degraded airsheds" and promised cleaner fuels, but policy without enforcement remains wishful thinking. Laws are drafted, agencies formed, and circulars issued—but the air does not obey paperwork. It obeys emissions.

The common thread across these crises—whether a falling bearing pad, a burning warehouse, a crashing jet, or a choking sky—is the same: the absence of accountability. Dhaka's tragedies are not isolated events; they are the natural consequences of a system that prefers announcements over action, show over vigilance. Our resilience has become a polite word for endurance. We survive not because our systems work, but because individuals—drivers, doctors, firefighters, neighbours—do what institutions fail to do.

And so, every day in Dhaka becomes an act of collective improvisation. We cross roads that might collapse, inhale air that might kill, enter buildings that might burn, and stand under infrastructure that might fall. Yet we call it "development."

To live in Dhaka is to practice optimism against evidence. It is to wake each morning under the silent prayer that gravity, gas, and governance will all behave today. But when a city demands miracles to survive its own design, something fundamental has gone wrong. Survival should never depend on luck.

Dhaka dwellers deserve better—not as a privilege, but as a basic right. Development must mean more than construction; it must mean safety, foresight, and accountability. Until then, every death like Abul Kalam's, every fire, every crash, and every breath of toxic air will remind us that in this city, survival itself has become the most uncertain achievement.

H. M. Nazmul Alam is an academic, journalist, and political analyst based in Dhaka. Currently, he teaches at International University of Business Agriculture and Technology (IUBAT) and can be reached at nazmulalam.rijohn@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments