Why a logistics commission, not an authority, aligns with our realities

Last month, a private sector think tank proposed establishing a National Logistics Authority under the framework of the National Logistics Policy. The proposal initiates a discussion on the institutional framework best suited to serve Bangladesh's logistics future.

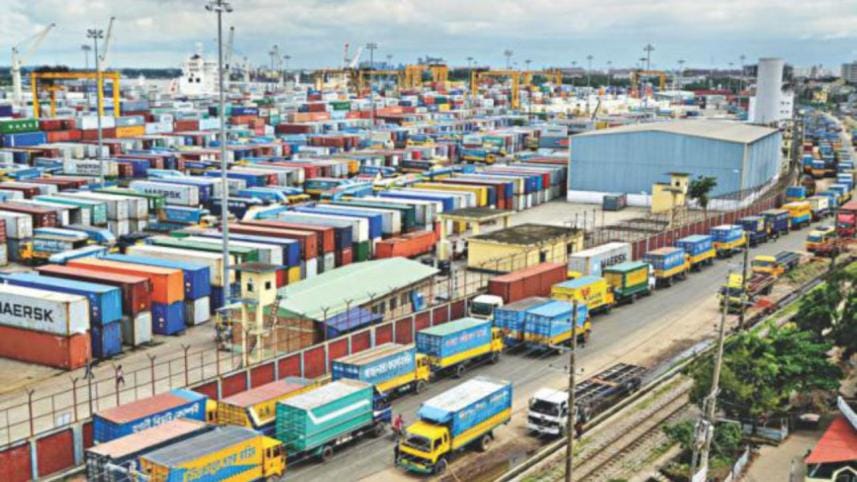

Recent developments illustrate the complex interactions within our logistics ecosystem. These include the Chittagong Port Authority (CPA)'s temporary suspension of permission for several French shipping giant CMA CGM's vessels following surcharge decisions, a warning to the Mediterranean Shipping Company for similar adjustments, and the brief truckers' strike that prompted CPA to review and postpone new entry fee measures. These skirmishes reflect the challenges of coordination among diverse actors in a fast-evolving trade environment. They underscore the need for a permanent, neutral platform that can align interests, mediate disputes, and uphold predictability across the entire logistics chain.

Bangladesh stands today on the threshold of a logistics transformation. The government's intent to reform policy, improve efficiency, and align infrastructure investment with trade facilitation remains a national priority. However, whether another "authority"—created within a single ministry—can truly manage such a multidimensional ecosystem remains a question. The word authority conveys decisiveness, but it also implies hierarchy. In a system as vast as logistics, which spans ports, customs, railways, roads, river transport, aviation, and private terminals, hierarchy without coordination may struggle to deliver results.

Logistics in Bangladesh is administered by a mosaic of agencies: National Board of Revenue (NBR), Bangladesh Railway, Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Authority (BIWTA), Roads and Highways Department (RHD), Civil Aviation Authority of Bangladesh (CAAB), and the Chittagong, Mongla and Payra port authorities, alongside hundreds of private logistics operators. Each has its own statute, budget, and administrative hierarchy. A ministry-led authority may coordinate some of these, but it cannot command them all. The outcome risks being partial compliance and parallel systems—the very fragmentation we hope to resolve.

This fragmentation already exacts a measurable economic toll. Bangladesh spends as much as 16 percent of its GDP on moving goods from factories to customers, far above the global average of 10 percent. The country thus ranks 88th of 139 countries in the World Bank's Logistics Performance Index. Exporters face costly port dwell times; importers endure unpredictable charges; truckers and freight forwarders confront multiple permits, inspections, and levies. The issue is not the absence of policy, but the absence of a single accountable body to oversee performance across the entire supply chain.

What Bangladesh needs now is not another authority, but a national logistics commission—an independent, statutory institution created by parliament and accountable to the nation. It would not replace existing agencies, but serve as a coordinating and regulatory platform that harmonises them. The precedent exists: US's Federal Maritime Commission that oversees competition and transparency in maritime transport without controlling the ports or the lines themselves. A similar model can guide Bangladesh, ensuring fairness, data-driven oversight, and strategic coherence.

A commission would unify the six pillars of the World Bank's performance framework—customs, infrastructure, international shipments, logistics competence, tracking and tracing, and timeliness—under one dashboard. Its first mandate could be to publish a national logistics performance index, updated quarterly, showing key indicators such as port dwell time, customs clearance hours, and corridor reliability. Transparency is the foundation of accountability; what gets measured, gets improved.

Another key reform should be licensing integration. Today, a logistics company must maintain separate licenses for terminal operator, berth operator, ship handling operator, shipping agency, freight forwarding, customs clearing and forwarding agent, trucking, and warehousing, each requiring different renewals and subject to overlapping inspections. This encourages inefficiency and rent-seeking. A single digital nationwide licence, administered by the commission and valid across all modes, would drastically reduce bureaucracy and encourage professionalism. This system would encompass terminal operators, shipping lines, shipping agents, non-vessel operating common carriers, freight forwarders, customs clearing and forwarding agents, cargo consolidators, trucking companies, barge operators, and off-dock or private inland container depots and inland container terminals.

A commission could also act as a neutral arbitrator in cases of dispute. The recent tariff and surcharge decisions by shipping lines, and CPA's subsequent administrative responses, demonstrate that these situations require structured mediation—not confrontation. A regulatory platform empowered to hear stakeholders, assess cost justifications, and issue transparent rulings would prevent disruptions while protecting both business interests and regulatory fairness.

Predictability, not price control, is what trade needs most. Businesses can plan around known costs; they cannot plan around uncertainty. The commission's role would not be to fix tariffs but to enforce advance notification, disclosure, and fair review of all charges—from port handling to emergency surcharges. Such oversight would replace reactive decision-making with institutional dialogue.

Bangladesh's infrastructure boom, from bridges, ports to upgraded highways and rail links, has expanded the country's physical logistics capacity. Yet, it lacks the rules, data, and accountability mechanisms to ensure efficiency. A national logistics commission would provide that missing layer of governance.

To make such a commission effective, collaboration between the public and private sectors is crucial. Key institutions such as the Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA) and NBR must coordinate with private sector stakeholders, including trade organisations and sector-wise associations. Think tanks, supported by development partners, can help draft the legislation and define measurable standards. This alignment would transform logistics governance from fragmented supervision into unified accountability.

The commission could also serve as a collaborative forum—a permanent roundtable where all logistics actors can deliberate before disputes arise. Before any tariff adjustment, for example, it could host consultative hearings among port authorities, shipping lines, and trade associations to ensure clarity and fairness.

Critics may worry that creating another body risks bureaucratic expansion. A well-designed commission would do the opposite: streamline oversight by consolidating overlapping functions, eliminating duplication, and publishing unified metrics. Its legitimacy would come not from coercive power but from credibility, transparency, and dialogue.

Ultimately, Bangladesh's logistics story is one of competitiveness. Every hour lost at a port gate, every redundant licence, and every conflicting directive erodes the nation's export potential. As the country aspires to become a regional manufacturing and trade hub, efficient logistics will determine whether it climbs or stalls in the global value chain.

A commission offers a pragmatic and forward-looking solution. Bangladesh already has the infrastructure, the enterprise, and the intent. What it needs now is a single institution that ensures coordination without confrontation, progress without disruption, and regulation without rigidity. The question is no longer whether Bangladesh can afford to establish such a commission, but whether it can afford not to.

Ahamedul Karim Chowdhury is adjunct faculty at Bangladesh Maritime University, and former head of inland container depot at Kamalapur and Pangaon Inland Container Terminal under Chittagong Port Authority.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments