What socialist Mamdani’s victory means at the heart of capitalism

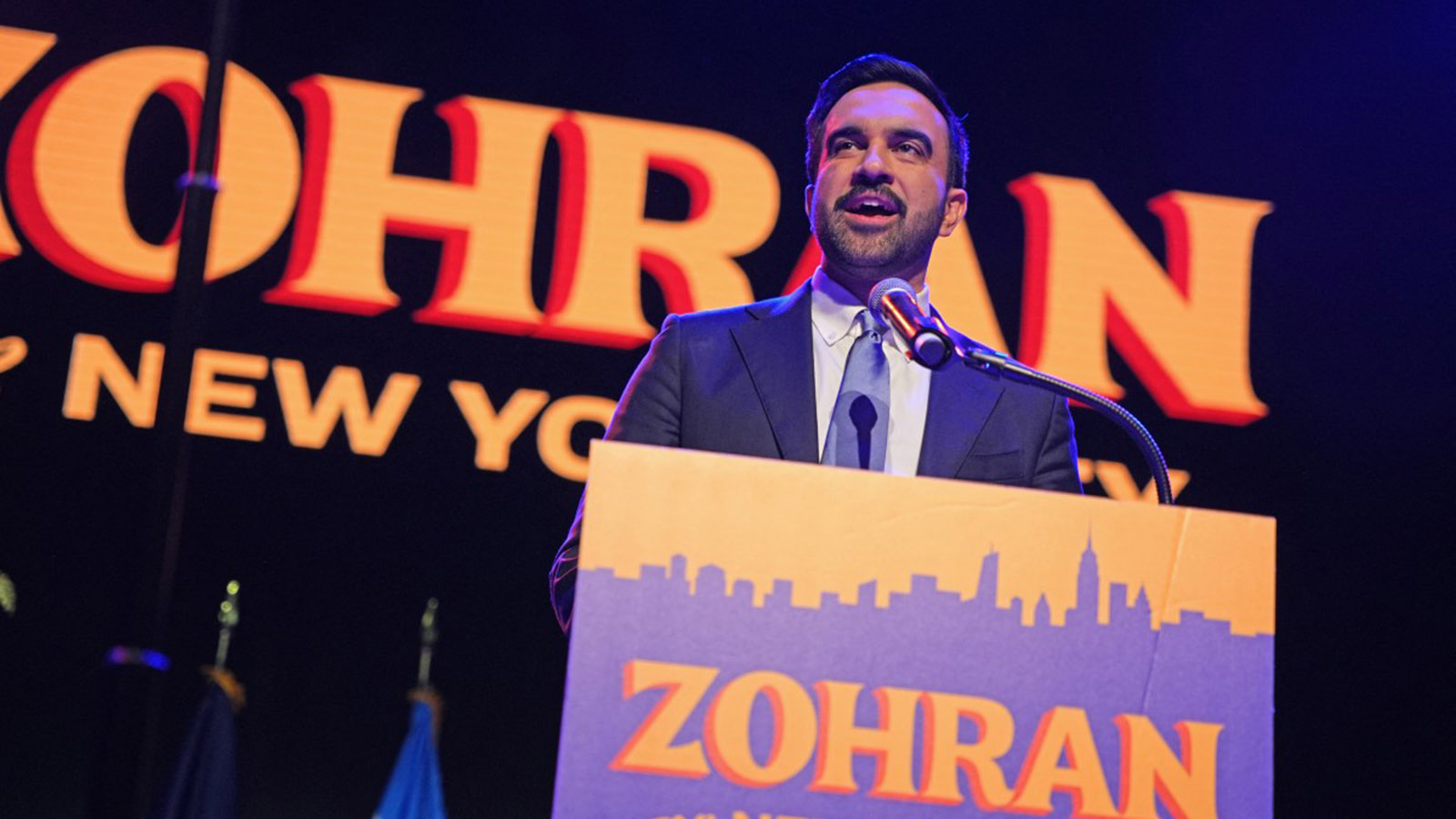

When New York City—the world's billionaire capital and command centre of a $55 trillion market economy—elected a democratic socialist as mayor on November 4, 2025, it stunned observers worldwide. Against the odds of a bruising, multimillion-dollar campaign bankrolled by billionaire patrons, voters chose conviction over capital by a large margin. The tremor of victory reverberated far beyond America's borders. Zohran Mamdani, a 33-year-old state assemblyman and son of Ugandan-Indian scholar Mahmood Mamdani and Indian-American filmmaker Mira Nair, defeated political heavyweight Andrew Cuomo to become the first South Asian-American Muslim mayor of New York. For a metropolis long synonymous with Wall Street capitalism, his triumph was more than a political upset—it marked a moral turning point, a redirection of the city's compass from profit to principle.

Mamdani's ancestry traced a remarkable arc across continents. His forebears migrated from Gujarat to East Africa as traders under British rule. His father, Mahmood Mamdani, was among thousands of South Asians expelled from Uganda by Idi Amin in 1972, later rising as one of Africa's leading post-colonial thinkers. His mother, Mira Nair, born in India and educated at Harvard, became an acclaimed filmmaker. Their son was born in Kampala in 1991, moved to New York at age seven. Before entering politics, he worked as a housing counsellor, helping tenants fight eviction—an experience that inspired his campaign slogan: Housing is a human right.

He joined the Democratic Socialists of America and entered state politics in 2020, quickly becoming a voice for tenants, workers, and transit users. His mayoral platform was unapologetically progressive: fare-free buses, rent freezes, universal childcare, and a gradual rise of the minimum wage to $30 by 2030—financed through higher taxes on corporations and millionaires. Critics called it utopian; supporters called it humane. What sounded radical in the citadel of finance resonated with ordinary New Yorkers exhausted by inequality and living costs. When ballots were counted, the city that shelters more billionaires than any other had chosen a candidate who rides the subway and speaks for wage earners.

In a world where identity and religion often dominated discourse, Mamdani's message of economic fairness and dignity of labour found cross-ethnic appeal. That shift held lessons for Bangladesh, where faith and faction often eclipse justice. Dhaka's realities echoed New York's in miniature: rising rents, congestion, and widening income gaps. The recent eruptions of labour unrest in Gazipur and Narayanganj over wage disparity were reminders of what happens when grievances fester. If the world's richest city could debate rent justice and free public transit, developing cities could too—adapted to local realities.

For Bangladesh, engulfed in struggles of inequality, youth frustration, and urban hardship, Mamdani's story carried both inspiration and warning. His victory signalled that rhetoric without results would erode faith in reform. Despite opposition from powerful donors, party elites, and a chorus of establishment endorsements—including that of President Donald Trump—voters refused to be swayed. They looked past the political choreography and chose authenticity over affiliation, conviction over calculation.

Mamdani's grievances resonated across nearly every great city—from New York and Los Angeles to London, Dhaka, and Chattogram—where residents face soaring rents, stagnant wages, deteriorating public services, and a growing sense that political power has drifted far from ordinary lives. His campaign captured a universal discontent: the widening gap between prosperity on paper and poverty in practice. What New Yorkers ultimately voted for was not just a new mayor, but a new moral compass—one that spoke to the anxieties of an urban generation long priced out and politically abandoned. His ascent marked not only the political awakening of a generation but also the rebirth of faith in democracy's promise: that power must serve people, not the privileged few. Mamdani's victory signalled a revolt against despair, inequality, and the politics of spectacle. Cities like Dhaka, Chattogram, Nairobi, and São Paulo—all facing the same divides between privilege and precarity—could find in New York's transformation a mirror of their own struggles and hopes.

To declare oneself a socialist in New York had been an act of both courage and faith—faith that democracy could still humanise capitalism. Whether Mamdani would deliver remained uncertain. City budgets are constrained, union politics complex, and corporate lobbies resistant. Yet, his election itself marked fatigue with the creed that markets alone guarantee prosperity. The 2008 financial crisis, pandemic inequalities, and the housing collapse had exposed capitalism's moral deficit. Mamdani's victory did not erase it, but it revived the conversation about what an ethical economy should look like.

For Bangladesh, the lesson was equally urgent. Growth without equity breeds discontent; equity without fiscal discipline breeds instability. The test for any democratic socialist—whether in New York or Dhaka—was to engineer fairness without undermining efficiency. Compassion had to coexist with competence. Bangladesh's export-led growth had created wealth but also a class divide between owners of capital and workers who generate it. Mamdani's policy ideas—stronger tenant rights, wage justice, and investment in public services—illuminated the same structural questions Bangladesh faced, though on a vastly different scale.

His rise also broadened the definition of immigrant success. For decades, the diaspora's triumphs were measured in business or science, becoming engineers or doctors. Mamdani introduced a new archetype: the public servant guided by ethics rather than accumulation. His victory showed that moral conviction, not money, can be a form of power. For young Bangladeshis abroad, this was quietly revolutionary. It legitimised political engagement and civic responsibility as paths of honour, not merely assimilation.

The global meaning of Mamdani's ascent lay in its paradox. The son of refugees and intellectuals now governed the city that symbolises global capitalism. A child of colonial and post-colonial displacement now presided over a financial empire whose logic once displaced people like his ancestors. That reversal challenged the old geography of power—the idea that wealth, wisdom, and leadership must flow only from the North to the South.

In the age of inequality, Mamdani's victory offered a glimpse of what could become a new social contract: capitalism tempered by conscience. The challenge was immense. If he failed, conservatives would claim vindication; if he succeeded, he could redefine progressive governance for a generation.

The implications stretched far beyond America. For developing nations, the debate he reignited—how to balance growth with fairness—remained the central economic question of the century. Wealth without justice breeds unrest; justice without growth breeds paralysis. The equilibrium between the two is the essence of sustainable democracy. Mamdani's attempt to find that balance in the world's most capitalist city became a political experiment worth watching.

For Bangladesh, engulfed in struggles of inequality, youth frustration, and urban hardship, Mamdani's story carried both inspiration and warning. His victory signalled that rhetoric without results would erode faith in reform. Despite opposition from powerful donors, party elites, and a chorus of establishment endorsements—including that of President Donald Trump—voters refused to be swayed. They looked past the political choreography and chose authenticity over affiliation, conviction over calculation.

A video clip by MSNBC shows The New York Times managing editor Carolyn Ryan saying that Mamdani's appeal is "reminiscent of Trump" for the way he "made people feel seen and heard," capturing the emotional undercurrent that drove voters to defy establishment endorsements and side with conviction over convention.

His rise reflected a deep yearning for representation that transcended labels—a politics grounded not in ideology but in empathy, charged with the emotional voltage of affection, where people felt recognised rather than managed.

Dr Abdullah A Dewan is professor Emeritus of Economics at Eastern Michigan University (US) and a former physicist and nuclear engineer at the Bangladesh Atomic Energy Commission. He can be reached at aadeone@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments