What does ‘good history’ look like?

It is impossible not to ask this question, given the current state of history as a public discourse in Bangladesh. But what is "good history" in the first place? What does the qualifying adjective good imply? The question, ahem, might be understood less as an inquiry than as a provocation—a prompt for indulging in a bit of soul-searching about such perennially indeterminate concepts as nationhood and national identity, and about their intersection with history.

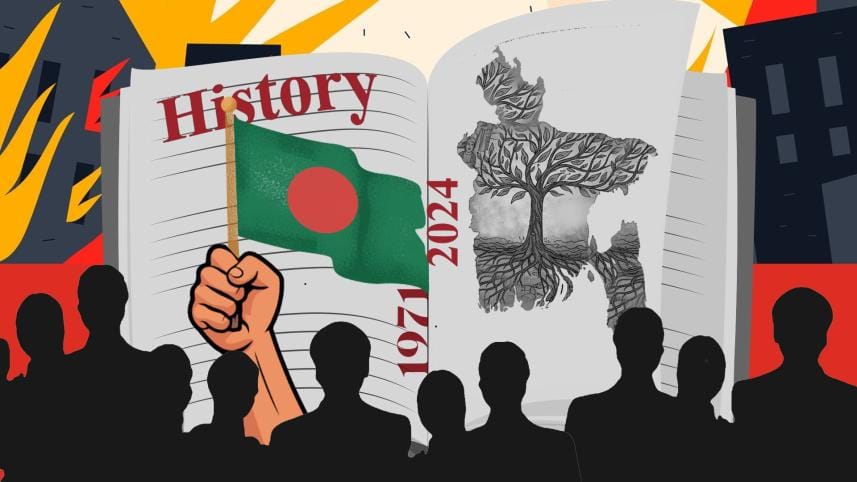

Since Bangladesh's independence in 1971, the history of the country's liberation war has been the site of competing political claims, denials, suppressions, glorifications, centralisations, and partisan orthodoxies. In the wake of the August 2024 uprising, a new generation of spontaneous efforts has emerged to revisit the "history" of Bangladesh's Liberation War, ranging from reassessments of the roles of different historical figures to renewed debates over the political origins of the war itself. What has unfolded since independence—especially before and after August 2024—is a systematic erosion of history as a subject of critical inquiry, one grounded in evidence and pluralism.

Given our civil society's failure to cultivate a robust public understanding of history, one driven by fact-based research and reasoning rather than personal beliefs or social-media-driven partisanship, it is crucial to articulate what "good history" is or could be in the sociopolitical context of Bangladesh. It would not be illogical to assume that the question—what does good history look like?—should be a worthwhile public conversation on history as a key driver of human capital, citizenship, and nation-building.

When, last year, Badruddin Umar stated, albeit in a sensationalising tone, that 80-90 percent of the "official" history of Bangladesh's Liberation War is false, he must have had some thoughts on what "not false" history might be instead. I wish he were alive today to articulate his thoughts on the question of good history.

No historian should be able to answer the question on good history without a degree of trepidation, ambivalence, and uncertainty. Yet a serious historian, or anyone who believes in history as a reasonable way of understanding the past, would at least pose a counterquestion: How does one define "good history"? And that, in turn, gives rise to another difficult question: What is history in the first place?

Let's imagine some hypothetical scenarios. If we asked Aristotle what a good history of Bangladesh's Liberation War would look like, he might suggest examining the war objectively and sincerely, narrating what actually happened on the ground and what caused those events. He would recommend distinguishing between history and poetry or philosophy, which, in his view, are primarily concerned with what could or should happen.

German philosopher Hegel would answer the question differently. He would present history of the war as the Bangalee nation's progressive journey toward reason and freedom, a piece in the puzzle of macro-history's self-rationalising movement toward the highest consciousness. If we posed the same question to another German, Leopold von Ranke, he would advise us to write the war's history based on empirical sources. The task of the historian, he would argue, is not to judge, but to understand how things happened by examining hard evidence, while avoiding philosophy and speculation.

How would Rabindranath Tagore define the history of the Liberation War? If Hegel's history represented the forward march of reason—of which Bangladesh's Liberation War was one part, as was the French Revolution—then Tagore's history of the war would be the Bangalee nation's journey towards spiritual realisation, a humanist and moral unity that transcended nationalist and swadeshi narratives. If we asked Mahatma Gandhi the same question, he would likely encourage us to write the history of the war from the perspective of the masses (aamjonota) and the Muktijoddhas with their armed struggles, rather than from the grand narratives of heroic leaders.

Thus, the question—what is history?—depends on whom you ask. The diversity of answers itself indicates history's power to tell human stories from myriad angles. There is, indeed, a history of histories.

Today, within liberal academic circles, the fair-minded historian tends to view history as a broad disciplinary practice in which the "grand old histories" of civilisational scale—meta-narratives, causation, teleological progress, hagiography, and "Western civilisation"—have been extensively challenged by critical histories of "other" peoples and their experiences, social history, cultural history, economic history, gender history, histories of technology, and, more importantly, an empathetic and justice-oriented search for historical evidence that has been traditionally ignored or silenced in favour of the triumphant narratives of victors.

Contemporary critical historians tend to avoid either-or dichotomies, linear narratives, and false nation-centrism. Instead, they reveal how peoples, regions, nations, and cultures have encountered one another through broad networks of trade, human mobility, cultural exchange, technology transfer, and what the American sociologist and historian Immanuel Wallerstein called world-systems—a unitary economic system that binds all nation-states of the world.

The interaction of macro- and micro-histories produces a wide range of perspectives on any historical event. The global and the national interweave in infinite varieties to give rise to histories of multiple dimensions, scales, and philosophies. From this angle, any contemplation of "good" histories must be a dynamic and open-ended process of thought. How, then, can we begin to situate 1971 within the broad arc of "good" histories?

Muyeedul Hasan's Muldhara '71 (1986), M. R. Akhtar Mukul's Ami Bijoy Dekhechi (1993), Archer Blood's The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh (2002), Nurul Islam's Making of a Nation (2003), and Gary Bass's The Blood Telegram (2013), among others, are all valuable sources for constructing an intellectually nuanced history of Bangladesh's Liberation War.

Whether a particular approach to history is acceptable or not is less important than understanding history as a vigorous inquiry that avoids the traps of deterministic certainties, linear causalities, hagiographic exuberance, and sweeping generalisation. Unfortunately, critical, unafraid-to-tell-the-whole-truth histories have faced severe backlash over the last few decades, particularly in the United States. What has been pejoratively described as "woke" histories—those that bring to the fore the experiences of marginalised peoples and uncomfortable truths—have become political targets. In these uncertain times, many nations and their political leaders continue to weaponise history to advance partisan or nationalistic agendas.

The current US administration, for instance, seeks to create a "beautiful" American history—one unblemished by the histories of slavery, racial and gender discrimination, the traumatic struggles for civil and human rights, and genocide. In this discriminatory view, history must serve as an uplifting project that reinforces political domination. Similarly, anti-immigrant politicians in Europe frequently invoke the historical and racial unity of European civilisation, now allegedly threatened by the "invasion" of incompatible communities.

In Bangladesh, the recent "reset button" proclamation has unwittingly promoted a history of erasure in the name of building a brand-new future. The reset argument seems to imply: What is the point of getting stuck in the past?—as if the past has nothing to do with the ways the future takes shape.

We are indeed passing through a crisis of conscience. We find ourselves increasingly unsettled by the militarisation of history—its ability to divide and make people confrontational, to invent new nationalist myths and alternative triumphs, to provoke radical religiosity, and to cultivate a convenient culture of amnesia in which the past becomes a playfield for selective remembrance. Can a public conversation on "good history" serve as an antidote to this growing culture of weaponised history?

Is there a "good" history that we can champion, one that keeps us committed to the pursuit of knowledge as a fundamental means of understanding our existence, or to public interests greater than ourselves, our parties, and our self-comforting, social-media-shaped beliefs? Ultimately, the question about a "good" history should be understood less as a question than as an aspiration, one essential to a democratic society.

Dr Adnan Zillur Morshed is a public thinker and academic.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments