Venezuela attack: When a president is abducted, sovereignty becomes conditional

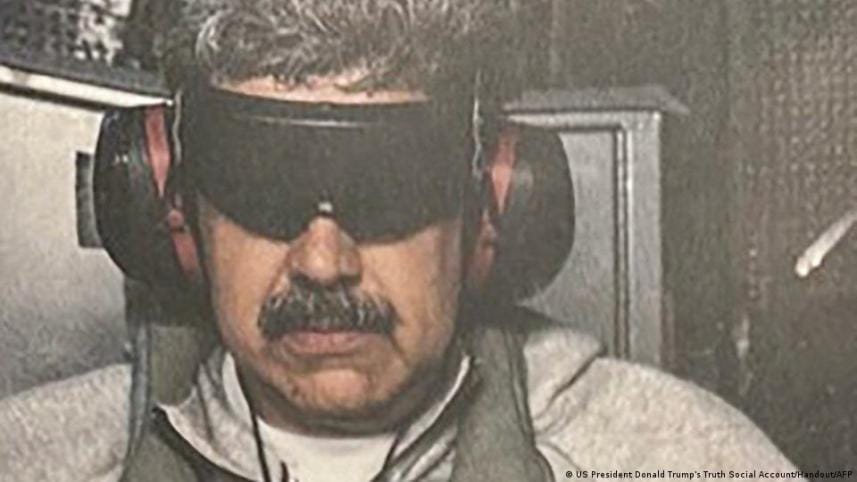

The United States' overnight assault on Venezuela and the seizure of President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, are being sold as an anti-drug mission and a law enforcement action. Yet the White House has already described the aftermath in the language of control, not custody. Trump spoke of the US "running" Venezuela, rebuilding its oil sector, and keeping the option of "boots on the ground" on the table. He also blamed Venezuela for stealing US oil interests, saying Washington would take them back. In essence, a raid marketed as an "arrest" is being packaged for a geopolitical reset with economic spoils.

This is not a semantic dispute; it goes to the heart of the post-1945 trade-off between states, under which borders became legal facts protected by international law, not negotiable obstacles to be overcome by force. The UN Charter's baseline rule is explicit: states must refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state. The exceptions are deliberately narrow: UN Security Council (UNSC) authorisation, and self-defence after an armed attack.

By those standards, Washington's legal story reads more like a post hoc alibi. International law experts, including Geoffrey Robertson KC, stated that the attack on Venezuela violated Article 2(4) of the UN Charter and constituted the crime of aggression, regarded as the gravest offence under international law. According to international law, drug trafficking and gang violence are criminal activities that do not meet the accepted threshold for armed conflict that would justify military force, and a criminal indictment does not itself authorise armed force to depose a foreign government. Experts criticised the US administration for trying to describe the operation as both a targeted law enforcement mission and a potential prelude to long-term US control of Venezuela. If force can be recast as policing, then the prohibition on force becomes a technicality, and any powerful state can claim it did not "invade"; it merely "arrested." The world should not turn an invasion into due process simply by attaching handcuffs at the end.

The way the operation was executed compounds the damage. Congress was not notified in advance, and Trump defended secrecy by arguing that lawmakers might have leaked the plan. In a democracy, oversight exists to slow down reckless force and provide clarity about aims, costs, and exit routes. Here, the constraint is treated as the threat. For smaller states, the lesson is stark: even Washington's internal guardrails can be switched off when a foreign target is politically useful, and the public relations dividend is large.

International reaction has been swift. The UN secretary-general's spokesperson called the developments a "dangerous precedent" and stressed the need for full respect for international law, including the Charter. Many states have also reacted strongly. Spain rejected an intervention that violates international law, while Mexico explicitly cited the UN Charter in condemning unilateral military action. Brazil's president warned that attacking countries in flagrant violation of international law is a first step towards a world where the law of the strongest prevails. These are not abstract anxieties. They are a recognition that once this threshold is crossed, it will be crossed again.

Some leaders, particularly in Latin America, have also celebrated Maduro's removal, while others are seeking urgent multilateral action, including UNSC engagement. This is how the hemisphere is dragged back into a geopolitics of camps, clients, and punishments, the dynamic that has historically produced coups, proxy violence, and lasting institutional trauma. It also puts every regional government under pressure to prove loyalty to one side or the other, eroding the space for independent foreign policy and regional problem-solving.

This is where the incident stops being "about Venezuela" and starts being about sovereign security everywhere. If a superpower can seize a sitting leader, fly him out for trial, and then speak casually about administering the country, sovereign equality is downgraded from a right to a privilege. Smaller states will draw rational but destabilising conclusions—aligning with a patron because neutrality is unsafe, investing in deterrence because the law is unreliable, and hardening internal security and labelling dissent as "foreign-backed" because the fear of intervention becomes politically useful.

The timing magnifies the damage because this action lands in a world already saturated with norm-breaking uses of force. In September 2025, Israel struck in Doha, Qatar, targeting Hamas leaders and drawing accusations of sovereignty breach from a Gulf state central to mediation. In June 2025, Israel's operation against Iran escalated into an air war, and a US strike hit Iranian nuclear sites before a ceasefire, showing how easily limited operations become escalatory templates. Despite a ceasefire, Gaza's health ministry puts the death toll above 71,000, and reports continued killings. In Europe, Russia's war in Ukraine grinds on, with fresh drone strikes reported even as diplomats pursue talks. In East Asia, China has staged major live-firing drills around Taiwan, tightening tension in a region already primed for miscalculation.

Against this backdrop, Venezuela is not an isolated eruption; it is another crack in the same dam. Washington's strike may hand Beijing rhetorical ammunition and potentially embolden China's territorial claims, even if it does not trigger an immediate Taiwan attack. The hypocrisy is strategic as well as moral: a country that invokes the Charter when convenient cannot demolish the Charter when impatient and expect rivals to keep respecting it.

None of this is in defence of Maduro. Accountability for abusive rulers is necessary. But accountability delivered by invasion does not strengthen law; it replaces law with dominance. A rules-based world cannot survive on the logic that illegal force becomes acceptable if the target is unpopular and the actor is powerful. If Maduro must face justice, it should come through lawful cooperation, multilateral pressure, and credible international mechanisms, not through a precedent that normalises cross-border abduction and open-ended political control.

Barrister Khan Khalid Adnan is advocate at the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, fellow at the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, and head of the chamber at Khan Saifur Rahman and Associates in Dhaka.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments