The significance of March 7

"All history is contemporary history, for we cannot understand the past without reference to the present."

– Michel Foucault

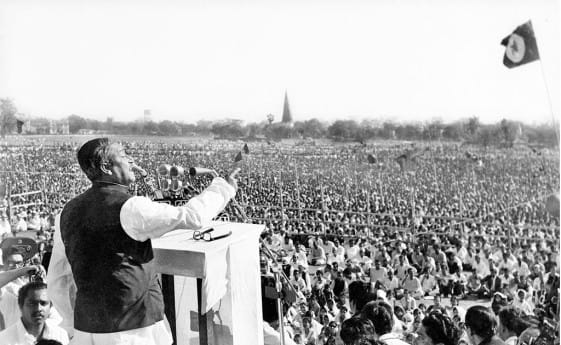

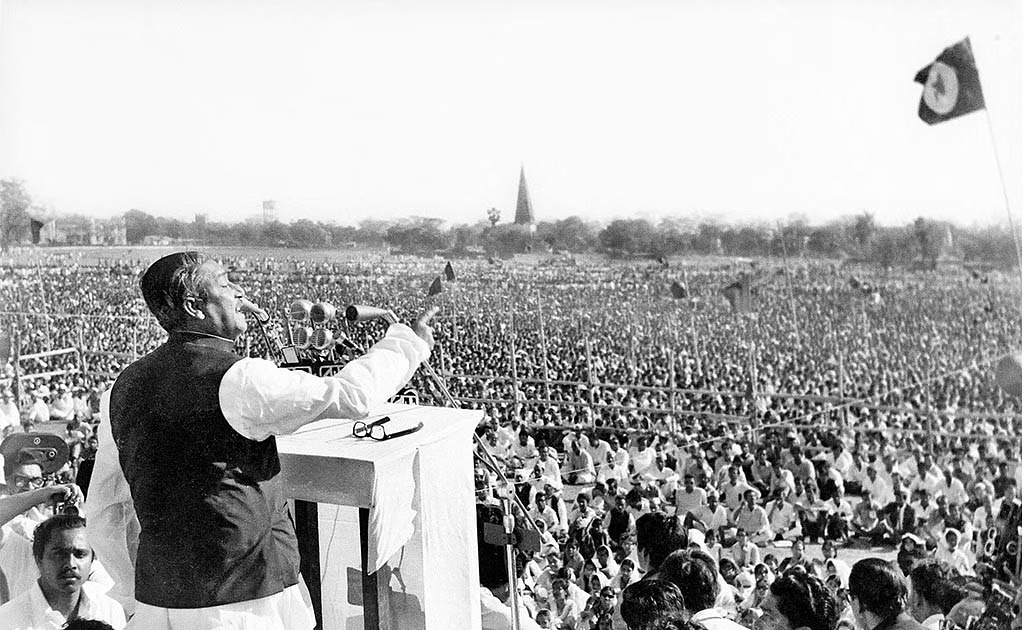

History, as Walter Benjamin suggested, is not a seamless continuum, but a battlefield where memory is contested, reinscribed, and often erased in the name of constructing, if not privileging, dominant narratives. Michel Foucault added that "All history is contemporary history," emphasising that our understanding of the past is inextricable from the present. Together, these perspectives illuminate how the meanings of March 7 are not fixed but continuously shaped by contemporary power dynamics. In Bangladesh, March 7, 1971 remains one such battleground: a day at once foundational and yet unsettled in its meaning. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's speech at the Racecourse Ground (now Suhrawardy Udyan) in Dhaka was, for many, the moment that crystallised people's aspirations for self-determination in the erstwhile East Pakistan, a speech that hovered between caution and inevitability, revolution and restraint. It was not a formal declaration of independence, yet its impact made armed struggle almost a foregone conclusion. However, in the shifting political landscapes of Bangladesh, the significance of this day has been repeatedly contested, appropriated, and put under erasure—not in the simple sense of being forgotten, but in the Derridean sense of being put under erasure, or crossed out, while remaining legible beneath the strikethrough.

Writing history by erasing it

To write history "under erasure," as Jacques Derrida suggested, means to render certain events both visible and obscured at the same time—crossing them out while leaving a trace of their original significance. Erasure here does not signify absence but a mode of selective remembering, where inconvenient or competing narratives are marginalised, if not obliterated. The selective remembering of March 7 serves specific political functions. Under Ziaur Rahman and Ershad, the downplaying of Mujib's role in the liberation struggle helped build the legitimacy of military figures. Conversely, the revival of March 7 by the Awami League reinforced the party's control over the nation's founding narrative, aligning it with their ongoing political interests. In Bangladesh, the fate of March 7 has exemplified how history is reshaped to align with contemporary power politics. The day, once celebrated as a moment of political culmination, was downplayed during the regimes of Ziaur Rahman and Ershad. The very discourse around the nation's founding was rewritten to foreground an alternative lineage of nationalist heroes and military figures. This was not merely a matter of omission, but an active reconstitution of the past—termed "silencing the past" by Michel-Rolph Trouillot, where historical processes are deliberately obscured to shape collective memory.

Conversely, when the Awami League returned to power, March 7 was resurrected and elevated to canonical status. The UNESCO recognition of Mujib's speech as part of the Memory of the World Register in 2017 further institutionalised its significance. But here too, history was being rewritten—this time not by erasing March 7 but by fixing it within a singular, state-sanctioned narrative. The radical openness of the speech, its interplay of defiance and strategic ambiguity, was smoothed over in favour of a retrospective teleology that presented it as the inevitable prelude to independence. In both cases—whether through suppression or canonisation—the past was not simply recorded but actively rewritten to legitimise contemporary political formations.

How history writes itself

Yet, history, as much as it is written by the victors, also writes itself in ways that evade control. The very fact that March 7 has had to be repeatedly reinterpreted, erased, and reinscribed suggests that history is not a fixed script but an ongoing process of negotiation and (de)(re)legitimation. The instability of its meaning points to the limits of historical (fore)closure—what Derrida might call the impossibility of fully mastering the trace. No matter how regimes attempt to frame March 7, its polysemy resists final domestication.

The Annales School stresses the importance of long-term, structural forces—such as economic inequality and regional disparities—over individual events. In the case of March 7, this means that while Mujib's speech was a critical moment, it was also shaped by decades of social and economic unrest in East Pakistan. March 7 was not just a product of Mujib's rhetoric; it was the culmination of decades of agrarian unrest, linguistic nationalism, and economic disparity between East and West Pakistan. The Annales historians would argue that while political figures shape history, deeper material and social forces constrain and direct their actions. Thus, the repeated contestation of March 7 reflects not just shifts in political power but enduring structural tensions in Bangladesh's postcolonial development.

Foucault's archaeology and genealogy of knowledge, on the other hand, provide a framework to analyse how March 7 has been constituted as an object of discourse. His archaeological method would trace how different political regimes have constructed the meaning of the speech, revealing the discursive formations that have rendered it either central or marginal at different historical junctures. Genealogy, in turn, would expose the power relations embedded in these narratives—how successive governments have used the memory of March 7 to consolidate authority, exclude rival interpretations, and create a disciplined historical consciousness.

For instance, under Ershad's regime, the speech was framed not as a rallying cry for independence but as a moment of "containment" that prevented a full rupture. This construction of the speech as a "moment of strategic ambiguity" served to align it with a vision of a "unified" Bangladesh rather than the revolutionary rhetoric that many hoped for. In contrast, when the Awami League sought to reclaim March 7, it highlighted the speech as the definitive moment of defiance, a vision of Bangladesh's destiny that could not be ignored. Different political actors have read the speech through different lenses, some seeing in it the inevitable culmination of Bangalee nationalism, others seeing an instance where history exceeded the leader's cautious rhetoric. The history of March 7, then, does not simply belong to those who write it; it belongs to the event itself, to the people who filled the Racecourse Ground, to the contingencies that unfolded in the days and weeks after.

Moreover, the meaning of March 7 is shaped not just by those who seek to commemorate or erase it, but by the structural forces of history itself. The Liberation War that followed, the failures and successes of post-independence governance, the cycles of military rule and civilian politics—each of these moments has retroactively reshaped how March 7 is understood. To invoke Georg Hegel, history is often grasped only in retrospect, through the owl of Minerva taking flight at dusk. In this sense, the meaning of March 7 is never fully settled; it remains in motion, subject to new inflections and interpretations as the political landscape evolves.

The unfinished work of March 7

The fate of March 7 in Bangladesh's historiography is instructive of a larger reality: history is never merely about the past but remains an active terrain of struggle in the present. Whether through outright erasure, selective inclusion, or rigid memorialisation, the battle over history is ultimately a battle over power—over who gets to narrate the past and for what ends. The Annales School demonstrates how deep-seated structural forces—political, economic, and cultural—have continuously reshaped the meaning of March 7, embedding it within shifting frameworks of national identity and legitimacy. Meanwhile, Foucault's archaeology and genealogy expose the mechanisms through which knowledge about the event has been produced, controlled, and disseminated, revealing how history is not merely recorded but actively constructed.

And yet, history also carries within it the seeds of its own resistance; it writes itself in ways that no official narrative can fully contain. The significance of March 7, then, lies not in its uncontested enshrinement but in its persistent contestation. As a site of meaning in flux, it is continually rewritten yet never fully erased, always open to new interpretations and reconfigurations. The struggle over March 7 reflects the broader tension between historical closure and historical possibility—between the state's attempts to fix its meaning and the countervailing forces that insist on its multiplicity. In this sense, the work of March 7 remains unfinished, not because its historical significance is in question, but because history itself refuses finality. The epigram, "All history is contemporary history, for we cannot understand the past without reference to the present," underscores the idea that our understanding of history is always influenced by the present moment. Foucault suggested that history is never a neutral recounting of events; instead, it is continuously reinterpreted through the lens of current power structures, ideologies, and struggles.

This perspective, however, can hardly serve as an alibi for writing history by erasure, especially when erasure—or the trace left behind—becomes a tool for delegitimating alternative, overdetermined narratives. While history is always shaped by the present, the deliberate omission or distortion of past events, like the meaning of March 7, serves not just to reinterpret, but to actively control and suppress competing visions of the past, reinforcing the present power structures. In this way, the act of erasure becomes not merely a reflection of contemporary concerns, but a mechanism of power that determines which histories are visible and which are silenced, ensuring that the past remains aligned with the interests of the present.

Dr Faridul Alam is former faculty member at the City University of New York (CUNY) and a licensed social work practitioner. He writes full-time on interdisciplinary issues, primarily through the lenses of postmodernism and postcolonialism.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments