The ethics of machine judgement and the post-human condition

In a world increasingly shaped by algorithms, decision-making is stripped of human nuance. From predictive policing to hiring processes and social media content moderation, algorithms promise efficiency, scale, and objectivity. However, as these systems assume a greater role in shaping outcomes, they introduce a post-human condition where machines, not humans, are increasingly entrusted with life-altering decisions. The real question is: what is lost when empathy, reflection, and ethical reasoning are sidelined in favour of data-driven speed?

The promise of algorithmic decision-making lies in its precision. Yet, as scholars like Safiya Noble, author of Algorithms of Oppression, and Cathy O'Neil, author of Weapons of Math Destruction, highlight, these systems—far from being neutral—often reinforce existing social biases. Noble demonstrates how search engines propagate racial stereotypes, while O'Neil exposes how risk models in law enforcement and education disproportionately target marginalised groups. These aren't merely data errors; they are symptoms of flawed assumptions about fairness, often embedded within the algorithms themselves. In the post-human condition, these biases are perpetuated not by human malice but by automated systems that replace human decision-making without accountability.

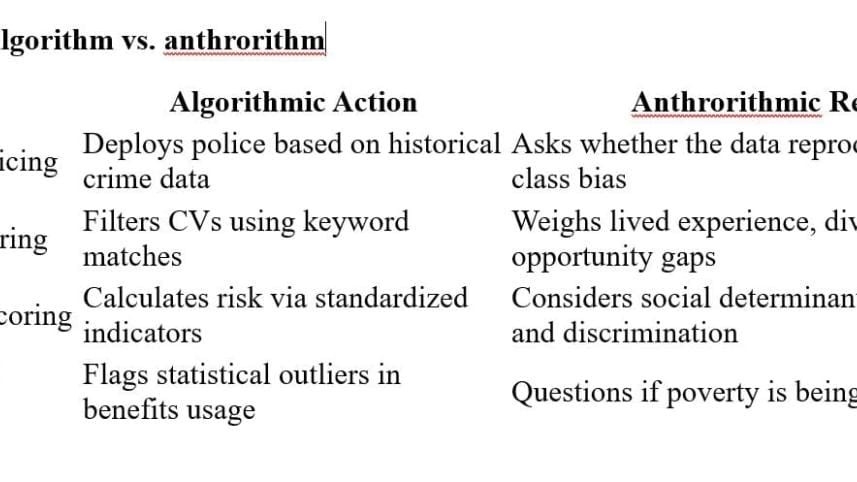

To address this, anthropologist Genevieve Bell introduced anthrorithms, a counter-model of reasoning that privileges human experience, ambiguity, and moral consideration. Unlike algorithms, which optimise for efficiency and predictability, anthrorithms pause for reflection. They resist the urge to reduce human lives to data points, acknowledging that logic cannot capture ethical judgement. In a world that increasingly privileges machines, anthrorithms challenge us to retain our human responsibility to question, reflect, and care.

Algorithm vs anthrorithm: A quick contrast

This divide mirrors the historic gulf between science and the humanities, which CP Snow once described as "two cultures." Today, however, the stakes are much higher. In the face of climate collapse, surveillance capitalism, and digital inequality, the boundaries between the technical and the ethical, the computational and the human, are more fluid than ever. As historian Dipesh Chakrabarty argues, global crises demand a reconciliation between the scientific and the ethical, between the analytic and the interpretive. In this light, the rise of machine-driven decision-making is not simply a technological issue, but a cultural and ethical one that calls for more than just computational accuracy—it demands a human-centred reflection on what counts as justice.

Algorithmic thinking and the post-human condition

Algorithms excel at replication—they detect patterns, optimise decisions, and predict behaviour. Yet, they cannot fathom the complexities of human lived experience, nor can they account for moral nuances. As we cede more and more of our decision-making processes to machines, we are faced with the reality of a post-human condition, where the human element is not just sidelined but replaced. This shift is evident across various domains.

Consider predictive policing, where algorithms use historical crime data to predict where crimes are likely to occur. While seemingly objective, these systems often reinforce existing racial and class disparities. The data used to train them reflects historical patterns of discrimination, perpetuating the same biases in new, automated forms. Similarly, in hiring algorithms, candidates are assessed based on keywords or past hiring patterns, yet these systems often fail to recognise the value of lived experience, diversity, and human potential. In both cases, algorithms make decisions with cold efficiency, but they fail to reflect the ethical complexities inherent in human lives. Anthrorithms, in contrast, would pause to ask: who benefits from these systems, and who is left out?

In healthcare, algorithms are used to calculate risk scores for patients. These tools often rely on data from insurance companies, which may overlook the social determinants of health like poverty, systemic racism, and access to care. The algorithmic model may provide an efficient answer, but it fails to address the root causes of disparities in health outcomes. An anthrorithmic approach would not only consider the clinical data but also the context in which individuals live and the systemic inequalities they face.

In all these cases, algorithms provide clarity—but at the cost of context. They offer certainty, but without accountability. They are designed to optimise, but they cannot engage with the ethical dimensions of their decisions. This is the crux of the post-human condition: algorithms can process information with unmatched precision, but they cannot ask whether their decisions are just. This is where anthrorithms step in: they prioritise ethical hesitation over automated certainty, insisting that the responsibility for judgement cannot be outsourced to machines.

In practice: Algorithm vs anthrorithm

This intersection of algorithm and anthrorithm is where we must confront the limitations of technology. Algorithms offer clarity, but they are ultimately products of the data they are trained on, and that data is often as flawed as the systems that generate it. While algorithms may be optimised for speed and accuracy, they cannot reflect the lived realities of human beings, nor can they bear the ethical burden of their decisions. It is here that anthrorithms offer a critical intervention: they demand that we engage with the messy, contradictory, and often painful truths of human existence.

The global stakes of post-human ethics

The rise of algorithmic systems is not limited to the Global North. In the Global South, digital systems are often introduced through development initiatives or corporate agendas, with little regard for local context or social equity. In countries with weak regulatory frameworks, algorithms can be used to surveil entire populations, perpetuating neocolonial control over data. Anthrorithmic thinking demands a more equitable approach, where communities are not just subjects of data collection but active participants in defining the ethical contours of digital systems.

Global development programmes using biometric IDs or credit scoring systems may promise inclusion, but they often exacerbate inequalities by marginalising communities that lack access to digital infrastructure. Anthrorithms push back against this datafication, urging for justice in how technology is deployed. This is not just a technical issue; it is about who gets to define the rules, who gets to participate, and who gets excluded.

Reframing the role of machines in society

To create a just and ethical society, we must integrate anthrorithms into our technological frameworks. This doesn't mean rejecting algorithms, but rethinking how they are used. Algorithms must be held accountable, and their limitations acknowledged. The human element—the capacity for reflection, care, and responsibility—must remain central in decision-making, even as machines become increasingly sophisticated.

The solution is not to eliminate technology but to humanise it. Anthrorithms invite us to pause and reflect: what are the implications of these decisions? Whose interests are being served? Are we, in the name of progress, reinforcing old patterns of exclusion and injustice? These are not just ethical questions; they are existential ones. In the post-human condition, the challenge is not simply about better algorithms, but about ensuring that these systems are held accountable to human values, ethical judgement, and social justice.

In an age where machines increasingly make decisions about our lives, the most radical act may be to refuse to abdicate our ethical responsibility. Anthrorithms offer a path forward, insisting that technology must serve humanity, not replace it.

Dr Faridul Alam, a retired academic, writes from New York City, US.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments