The Bangladeshi model of dealing with bank crises

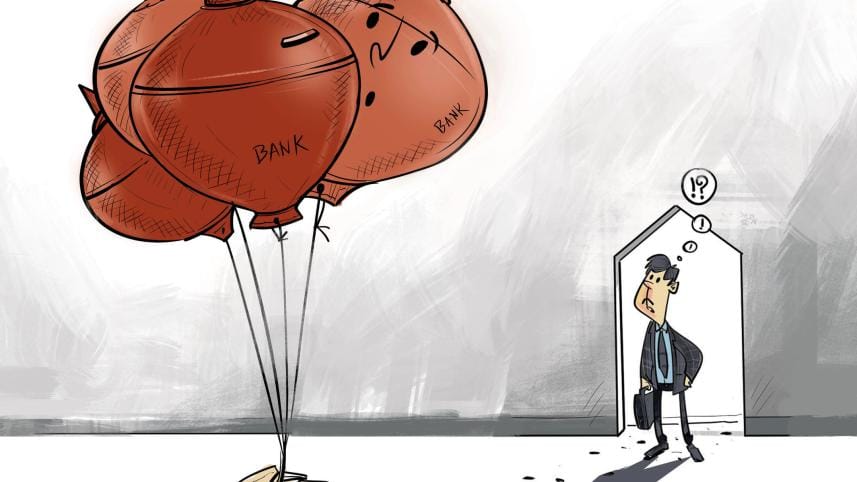

By now, everyone knows that Bangladesh's banking sector has some fundamental problems, non-performing loans (NPLs) being the top one. The growth of bad loans is mainly due to the business-politics nexus, lack of corporate governance, and weak judicial system. This growth has led to some banks often facing acute capital deficiency, which could lead to bank failure.

A bank fails when the market value of its assets declines below the that of its liabilities, and so, the market value of its capital, also known as net worth, becomes negative. Banks may incur losses for many reasons, and these losses are initially adjusted against capital. When the losses exceed capital, a bank becomes insolvent, faces a serious liquidity crisis, and fails to meet the immediate demand of its customers. The news rapidly spreads in the market, and panicked customers rush to withdraw their funds from the bank, which further aggravates its liquidity. The ultimate result is bank failure.

The failure of one bank may introduce systemic risk through which solvent banks may also fail when their customers panic and quickly withdraw their deposits. When there is a crisis of trust in banks, it is really difficult for some of them to remain operative. Bank failure is different from that of other institutions, because it has serious economic and political consequences. Hence, the governments in Bangladesh have tried to avoid this during their regime by injecting public funds, and the country never witnessed such a failure.

The Oriental Bank Limited was founded in 1987. From the very beginning, it fell into trouble because of insider lending, corruption, and mismanagement. Its accumulated loss stood at Tk 86.34 crore in 2001, which jumped to Tk 450 crore in March 2006 (State, Market and Society in an Emerging Economy, Chapter 10, Routledge). Overall capital deficit was Tk 877 crore. The bank was heading toward failure. However, in 2006, Bangladesh Bank (BB) dissolved the bank's board and floated a tender to sell its majority shares in 2007. The bank's paid-up capital was over Tk 700 crore, and the Swiss ICB Group won the bid and took control of the bank, purchasing 50.10 percent of shares for Tk 351 crore. The ICB Islamic Bank Limited has been operating in Bangladesh since then. It has turned into one of the worst performing banks in the country with massive non-performing assets.

Another story revolves around the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), founded in 1972. With its headquarters in London and incorporation in Luxembourg, this bank was working in Bangladesh too. The bank witnessed massive irregularities and mismanagement, and consequently collapsed in 1991. The institution's Bangladesh wing was also affected, but the BB came to the rescue. The local BCCI was restructured and Eastern Bank Limited was established in 1992. This new bank started its journey with 100 percent Bangladeshi owners and has been operating successfully. It is now one of the well performing banks, with an NPL rate of only three percent.

The Farmers Bank Limited was set up in 2013 and became the hub of financial corruption just within three years of its operation. Loans were approved without following the rules and practices. In 2015, the BB found that loans worth Tk 400 crore were sanctioned without proper documentation. Another investigation in 2017 identified even bigger irregularities involving Tk 500 crore. More than Tk 3,500 crore was drained from the bank. The bank faced a serious liquidity crisis and failed to honour even small-denominated checks. Consequently, authorities took action. The government forced four state-owned commercial banks and another state investment company to bail out Farmers Bank by purchasing the equity shares worth Tk 715 crore (60 percent stake in the bank). The institution was renamed to Padma Bank Limited. Failing to gain the people's trust, it then looked for a merger or acquisition, but no bank came forward. The institution is yet to improve its condition and remains one of the worst performing banks.

To improve the capital position of state-owned banks, the government injected a total of Tk 30,600 crore through budgetary allocation between 2011 and 2020. The year-wise allocation ranged between Tk 1,500 crore and Tk 5,400 crore during the period. It was Tk 1,700 crore in 2011, and Tk 5,400 crore in 2014, quadrupling in three years. The amount of capital injection varied depending on banking scandals. Some major scams occurred between 2012 and 2015, during which capital injection reached Tk 20,400 crore. However, the figure declined to Tk 2,000 crore separately in 2016 and 2017. It further reduced to Tk 1,500 crore in the following three years.

This type of solution has disastrous consequences since it creates a moral hazard – a situation which encourages stakeholders of banks to behave irrationally. For example, banks may take excessive risks, bankers may have less incentive to attain operational efficiency, and borrowers may be encouraged not to repay loans. If a bank knows its systemic importance and believes that it will be bailed out ultimately, it will not try to be efficient. Bailing out a bank using budgetary allocation is nothing but putting the burden of inefficient banks on the people.

Bank recapitalisation is not uncommon. A bank may be bailed out by capital injection if it is affected by systematic risk – a risk which affects the entire industry or market, like the pandemic or Russia-Ukraine war. The action must be defensible. There should be some simple performance indicators that have to be achieved within a certain period after recapitalisation. For instance, the default rate must be reduced to a certain level, say 10 percent, within a set timeframe.

It is unthinkable that these banks are still operative. While a bank can absorb only 12.5 percent of its losses, the potential losses of these banks are many times their absorption capacity.

The economy of Bangladesh is already burdened with a huge number of banks, some which came face to face with serious problems in managing liquidity, assets and capital. A number of banks have unusually high NPL rates. According to the BB data, National Bank of Pakistan has an NPL rate of 98 percent, Union Bank 95, ICB Islamic Bank 86, Padma Bank 59, BASIC Bank 58, and Bangladesh Development Bank's rate is 50 percent. It is unthinkable that these banks are still operative. While a bank can absorb only 12.5 percent of its losses, the potential losses of these banks are many times their absorption capacity.

The problems of some banks are chronic and capital injection will not solve them. They may be addressed by mergers and acquisitions, which will reduce the number of banks to an expected level. If that is done, the country's economy will present a healthy environment for the banking sector.

Dr Md Main Uddin is professor and former chairman of the Department of Banking and Insurance at the University of Dhaka. He can be reached at mainuddin@du.ac.bd

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments