A rudderless education policy is leading us astray

A question to test Bangla language skills – reading a passage with comprehension, deriving information from it, and expressing one's thoughts and reasoning cogently and grammatically – turned into a major controversy this month. The debate was not about whether the question in this year's Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) examinations tested students' language skills. It was the content of the passage that was found disturbing.

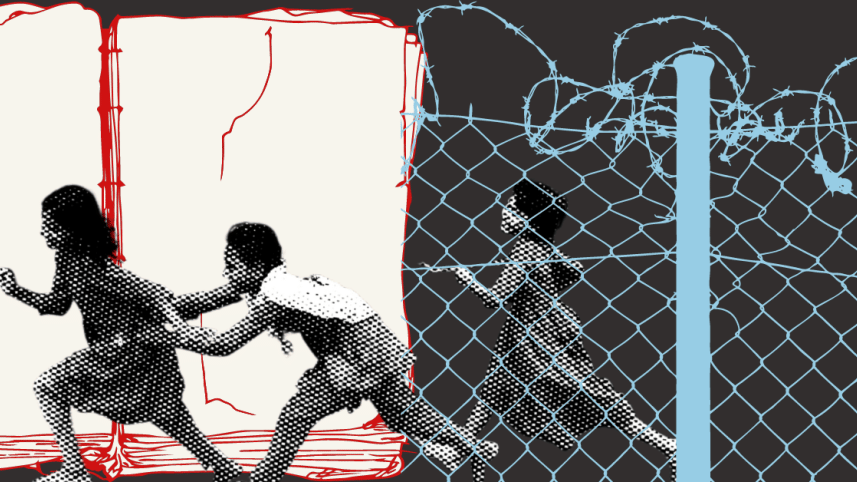

The passage spun a story about the enmity between two Hindu brothers, one spiting the other by bringing a Muslim neighbour next door, who behaved in the most un-neighbourly way, causing one of the brothers to take the extreme step of migrating to India with his family, leaving his ancestral home.

Whether the story has any connection with reality could be questioned. But it is clearly an inappropriate, insensitive, hurtful and provocative text that has no place in an exam paper for young students. The incident came to light because of social media. It could very well have been swept under the rug if a post on this issue hadn't become viral. The authorities doubled down on taking action – to investigate, find the culprits, and mete out punishment.

But does it end there? It has also been reported that during the ongoing HSC exams, another subject test used questions that maligned a well-known writer. Moreover, sets of question papers for "old and new syllabuses" were switched and wrong ones were distributed to students in one test, leading to the test being cancelled. There were allegations of a question paper leak during the SSC examinations last month, which the authorities denied.

Is there a pattern of incompetence, inefficiency, lack of accountability, and impunity among the education personnel and institutions in this country?

In 2017, in an exceptional initiative, a team of educators was invited by the then Education Minster Nurul Islam Nahid to undertake a "rapid enquiry" of the school syllabus and textbooks, student assessment and classroom practices, and make recommendations for change. The goal was to initiate some common-sense reforms early and consider measures that could be built into longer-term curricular, teaching and examination reforms. After several weeks of voluntary work by the team of academics and practitioners, a set of recommendations was prepared.

There were suggestions about the curriculum and textbooks – improving continuity and articulation of the content, reducing content burden, emphasising "learning to learn," rather than accumulation of facts, and making textbooks attractive and helpful for students, encouraging them to be actively engaged in learning. A model science textbook was designed by a team led by Prof Zafar Iqbal and Prof Mohammad Kaykobad. The ideas were to be followed up by the curriculum renewal exercise, which was foreseen to be undertaken.

There were recommendations regarding public examinations: dropping primary completion and junior secondary public exams, putting much greater emphasis on school-based student evaluation and short and quick public examinations (SSC and HSC), limiting them to core competencies in Bangla, English, maths, sciences and social studies. With one paper on each subject, the exams could be completed in one week, rather than being dragged on for several agonising weeks for students and their parents.

The matter of memorising guidebooks and notebooks, and the students' long hours with private tutors or at coaching centres, after school or even replacing school lessons, was a worry. It was agreed that these were symptoms of the disease and that there was no ready remedy without the changes in the current practice of teaching and learning and in examinations, and without finding other ways of assessing the students.

It was argued that teachers had to be supported and prepared to make the shift, and parents have to be brought on board. Setting questions for public examinations requires specialised technical skills, for which capacity and mechanism had to be built at the central level.

However, the decision-making culture and practice in our education ministry was such that nothing moved with any sense of urgency. The leadership at the ministry changed in January 2019. New people occupied senior positions. No one remembered the work done by the team of educators, and their proposals were lost in the bureaucratic labyrinth.

Ironically, the pandemic led to some decisions that were in line with the team's ideas, such as dropping the primary and junior school public exams, reducing test subjects and shortening the syllabus for SSC and HSC exams. But these things happened as ad hoc and emergency steps, rather than as part of deliberate reforms. The preference appears to be to return to "normal" as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, the curriculum renewal cycle, delayed by the pandemic, has begun and new syllabuses and subject contents are being piloted in a small number of schools. The institutional memory of work done and ideas generated earlier seem not to have been factored into this trial process. Nor have the lessons from the pandemic for specific changes been put forward in public education discourse.

Coming back to the current examination troubles, are we not reaping the harvest of poor decision-making and inertia in the system?

Reports in the press, commentaries, editorials and public reaction have expressed outrage about the negative portrayal of the characters representing the different communities and the likely inflammation of communal tension. They are also aggrieved by a possible failure of the public exam question-setting process.

The outrage is justified. But the real concern is that the episode is symptomatic of larger problems on two fronts. Many have spoken about the undercurrent of intolerance and communalism that remains strong in Bangladesh and is powered by the culture of political opportunism in the country, the region and the world that exploits and fans intolerance and communalism. The other serious problem is the rudderless navigation of our education system as described above. We need to be concerned as a nation about both.

Dr Manzoor Ahmed is professor emeritus at Brac University, chair of Bangladesh ECD Network (BEN), and vice-chair of Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments