Is It Sri Lanka’s ‘Arab Spring’ Moment?

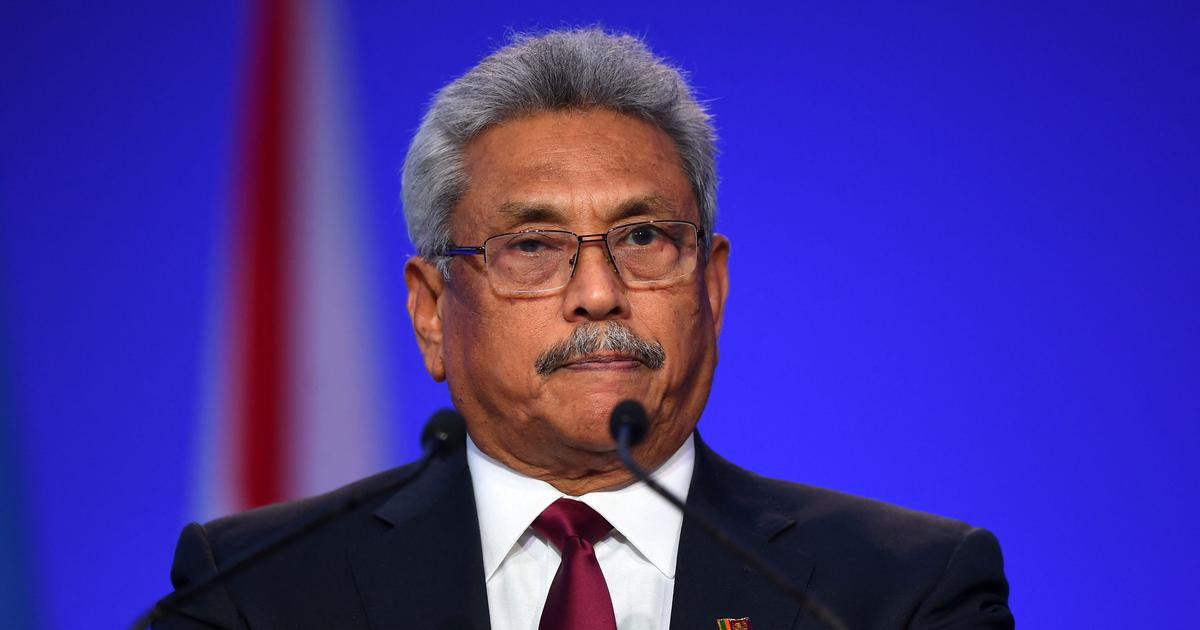

Two dates – May 9 and July 9 – will remain significant for the Rajapaksa brothers in Sri Lanka. It was on May 9 that Mahinda Rajapaksa, who enjoyed majority in parliament, resigned as the prime minister of Sri Lanka after his supporters clashed with anti-government protesters in the Galle Face Green, resulting in the death of two protesters. Exactly two months later, on July 9, the protesters, who had gathered from all over the country, forced Mahinda's brother and President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to flee the presidential house and took it over, in the culmination of what is described as "aragalaya" or struggle of the masses against a powerful regime.

Once the most powerful political family enjoying popular support and winning accolades for bringing peace by eliminating the LTTE, the Rajapaksas are now facing people's ire for corruption, maladministration and what people perceived to be a sense of entitlement – the manner in which the Rajapaksa family exercised power and enjoyed it with impunity. What started as the Mirihana protest on March 31, with police action against the protesters and later the student protest at Nugegoda and other parts of the country, was only the beginning of the end. Not to be browbeaten by the state power that Rajapaksas wielded, the crowd continued to gather at the Galle Face Green and engaged in peaceful protest with the slogan "GoGotaGama." This slogan captured youth imagination as students, activists, youths and the general public from all walks of life, overcoming the ethnic and religious divide, joined in large numbers spontaneously. Finally, they succeeded in unravelling the unpopular regime.

Now, the question is: What's next for the aragalaya? Both the political and economic roadmaps of Sri Lanka are bumpy. The opposition remains divided, and a consensual candidate to take over and form an interim government is not going to be smooth as the ruling party continues to enjoy a majority. Political instability is going to impact Sri Lanka's negotiation with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for the release of much-needed funds.

The movement started in April against the unfolding economic crisis in Sri Lanka as the island nation defaulted in its debt repayment. Economic distress was apparent with the fuel crisis, mounting inflation that led to the devaluation of Sri Lankan rupees. Food inflation increased to 80.1 percent in June 2022 from 57.4 percent in May 2022, while non-food inflation increased to 42.4 percent in June 2022 from 30.6 percent in May 2022. Hospitals announced that they did not have the essential medicines to carry out life-saving procedures.

This crisis has been in the making for the past few years. Sources of revenue were drying up due to a series of populist measures that the government adopted. For example, VAT was reduced to eight percent from 15 percent, tax-free threshold for turnover for VAT was raised from one million rupees to 25 million rupees. The government also abolished debit tax imposed on banks, capital gains tax, Pay as You Earn tax and debt services tax, while also withholding tax on interests and reducing income tax on the construction industry by half. The tourism industry had already shown signs of distress after the Easter bombing; the pandemic only accentuated the crisis. Remittances also declined as the construction and service industries in the Middle East were affected by the pandemic. According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL), in 2021, the total external debt service payments as a percentage of the export of goods and services increased from 13.2 percent in 2011 to 30 percent in 10 years, consuming one-third of the foreign currency earned. Moreover, 80 percent of the foreign debt was government debts. There was 33 percent depreciation of the Sri Lankan rupee against the US dollar this March, making the import-dependent country more vulnerable. Remittance flow reduced due to the depreciation of the Sri Lankan rupee.

The CBSL also admitted that the International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs), which Sri Lanka issued to raise finance, were priced at relatively high interest rates compared to the development assistance finances that the country received at concessional rates. The government's decision to finance large infrastructure projects with non-concessional and commercial borrowings resulted in the rise of the debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 60 percent.

Last year, the government's decision to introduce organic farming to save foreign currency resulted in a food crisis. Production of rice, the main staple, reduced by 20 percent. Production of tea, which fetches USD 3 billion annually, and rubber, another important item in the export basket, was affected. Businesses were unable to open a letter of credit due to scarcity of foreign currency. Inevitably, the government announced that it cannot service its USD 52 billion in debt. It started rationing fuel, resorted to load-shedding, announced "work from home" for its employees, and advised schools to hold online classes. All this mounted political disaffection. Already categorised as a "defaulter," the country would be moved to the D category if debts remain unpaid after the grace period.

Sri Lanka's economic fate still hangs in the balance. Political instability may be addressed with an all-party interim government and the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa on July 13. It is unlikely that the future government would be in a position to provide economic relief. The process of economic recovery will be long and arduous. Debt restructuring would be an important component of economic reforms. While the conclusion of the ongoing negotiation with the IMF would be an important first step, reforms are going to be unpopular and hurt the people who are still struggling. Taxes have to be imposed and unnecessary expenditure has to be curtailed. These were part of the IMF's USD 1.5 billion bailout package in 2016. Will there be another aragalaya against economic difficulties that the Lankans have to endure to put their economy back on track?

Sri Lanka's crisis has important lessons for the region. It is politically instructive to note that a powerful regime headed by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, wielding far-reaching executive powers, who was popularly elected only three years back, was shown the door by the people. It is evident that populist agenda cannot sustain regimes. Mismanagement of the economy, high-level corruption, and short-sighted economic policies steered by regime cronies rather than professional economists are a recipe for political disaster. South Asia has seen many instances of popular uprising against authoritarian and unpopular regimes; however, the Sri Lankan situation remains unparalleled in recent history as it was the economic crisis that underpinned what many describe as the Bastille moment, or its "Arab Spring," that jostled a political awakening.

Smruti S Pattanaik is a research fellow at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MP-IDSA) in New Delhi, India.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments