How Bangladesh must navigate the US-led trade shift

America's trade negotiations with its major trading partners, especially the 71 countries with which it maintains a high trade deficit, have put the world on the verge of entering a new global trade order. This trade order has emerged because of the US's high ad valorem tariffs—in addition to the usual product-specific most-favoured-nation (MFN) tariffs—with its bilateral trading partners having a high trade deficit. Tariff rates for individual countries have been estimated based on a unique formula whereby the rate of tariff is inversely related to the import of US products and positively related to the export of non-US products to the US market. Such a formula has little relevance to the rate of tariffs estimated under WTO rules. Although the US claimed to impose the tariff following the WTO articles on national security, it is difficult to justify that logic.

Since the US suspended the effectiveness of bilateral ad valorem tariffs against different countries for three months, most of these countries have undergone different levels of discussion and negotiation with the US. These discussions have taken place in four categories: (a) initiated negotiation with the US and reached an agreement (e.g. UK, Vietnam, China); (b) initiated negotiation with the US and yet to reach an agreement (e.g. Bangladesh); (c) initiated negotiation with the US but withdrawn midway (e.g. Indonesia); and (d) not entered into discussion and negotiation but rather threatened to impose retaliatory tariffs if the US imposed additional tariffs (e.g. Brazil, EU). It seems that the US carried out these negotiations in order to attain four objectives: (a) ensuring higher exports of US products to reduce its trade deficit; (b) ensuring higher revenue through additional tariffs to reduce US budget deficit; (c) encouraging foreign companies to invest in the US to increase domestic employment; and (d) discouraging countries from trading and investing with specific countries. It appears that individual countries' trade negotiations are dependent on their capacity to increase US imports and their level of resilience to withstand the US's retaliatory tariffs.

These bilateral negotiations have been taking place under a diverse range of structures and compositions—negotiations have involved not only setting overall ad valorem tariffs but also product-specific ad valorem tariffs. On the other hand, the negotiations include preferential tariffs/market access to US products in different markets. Hence, countries will have to deal with multiple challenges under the new trade negotiations. First, countries need to ensure their market competitiveness in the US market under the new ad valorem tariff. Second, countries need to import more US products in order to help reduce the US's trade deficit. Third, countries may find it difficult to export their products to other countries if those countries have bilateral agreements with the US covering products of interest. And fourth, countries may be artificially forced to import US products despite having cheaper alternatives available from other countries facing higher import tariffs/restrictions in the US market. Such new trade dynamics would severely undermine not only the export competitiveness of countries under trade agreements with the US but also force them to buy US products at less competitive prices or prevent them from importing from low-cost sources. Bilateral relationships between non-US countries would face a new level of strain because of changing trade preferences focused on the US, which may extend further to non-economic relationships between countries.

Bangladesh needs to take lessons from the multi-dimensionality of this new trade regime. First, Bangladesh is now fully concentrating on ensuring better market access to the US market. To ensure that, Bangladesh has offered a set of promises including: (a) reducing tariffs on products which are of the US's export interest; (b) promising to import a large volume of US products, which would contribute to reducing the bilateral trade deficit; (c) expecting reduced ad valorem tariffs on Bangladeshi products; and (d) promising to increase its local value addition of export products in order to ensure reduced tariffs in the US market. At the same time, a few other issues are being discussed, though they have not yet specifically entered the public domain, such as the US's concern over rising investment from some countries in Bangladesh. However, Bangladesh needs to keep in mind that such promises need to be tested against its bilateral trade with non-US countries, which are also key trading partners.

Any promise from Bangladesh's side for higher imports of the US's major export products to Bangladesh, such as soya seeds, LNG, wheat and chemicals, may hurt other countries' export interests to Bangladesh. Brazil, Canada and Ukraine are important sources of wheat. Similarly, Qatar is a major source of Bangladesh's import of LNG. Bangladesh's promise to import important strategic products such as arms and ammunition from the US may hurt the export interests of existing sourcing countries, such as China, India and others. Though these countries have other export destinations for the aforementioned products, they may consider the issue of losing an important share of their export market in Bangladesh as a serious blow. These countries may take retaliatory measures in other areas where Bangladesh's economic interests with them are quite high. For example, Bangladesh's manpower export to Qatar may face adverse effects. Similarly, Bangladesh's export to Canada may confront some ad valorem duties, or Bangladesh may face reduced credit support from China or China-dominated banks, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Exim Bank of China.

A commitment to raising domestic value addition requirements to 40 percent may initially appear positive for domestic industries. However, these industries are not yet ready to supply the required quantities while maintaining quality and timeliness. Therefore, the import of raw materials and intermediate products needs to continue for export-oriented industries. If the value addition criteria are increased, imports of certain key raw materials from important sources (China, India, Hong Kong) would need to be significantly reduced. Losing a favourable market by these non-US partners, especially China and Hong Kong, may not be received positively. Bangladesh's bilateral relations may come under pressure as a result of such a decision.

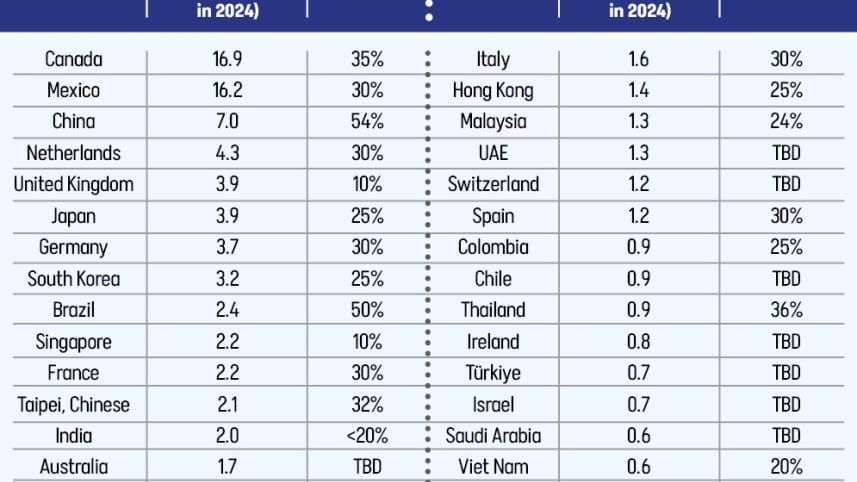

Bangladesh may face constraints in maintaining its existing level of exports with countries that have promised higher imports of US products. The US's annual export of $2 trillion (in 2024) includes diverse sets of products which include products of Bangladesh's export interest. Out of the US's 5,530 products (HS code at 6-digit level), there are products that are of Bangladesh's export interest, such as plastic products, agricultural products, chemicals, parts and equipment, etc., which may face direct competition and challenges because of the preferential market access granted to US products in those markets. These challenges are likely to be faced by small-scale exporters in different non-traditional markets in Asia, Europe, Australia and Africa.

It is apprehended that the US's high tariffs on major global exporters of agricultural products, raw materials, intermediate products and finished goods, such as Brazil, Canada, China and India, would make those products available at lower prices in non-US markets. This may have both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, these cheap agricultural products and raw materials would help countries like Bangladesh import them at lower cost. However, Bangladesh may not utilise that opportunity if it commits to higher domestic value addition for reduced tariffs in the US market. On the other hand, if Bangladesh commits to importing those products from the US, the opportunity to access low-cost products from non-US markets would be lost. Such costly procurement would raise the cost of products in the domestic market.

Bangladesh's trade deficit is evident with many European as well as Asian countries. Is Bangladesh ready to offer similar preferential market access through higher imports from those countries? Perhaps this is not possible. Hence, Bangladesh's ill-considered promises on trade may place it under pressure from other countries.

Overall, Bangladesh should deal with the US under the framework of its national trade, investment and procurement policies. More importantly, negotiations should not only consider the offensive and defensive interests in the US market. Rather, Bangladesh needs to consider the offensive and defensive interests with other key trading partners, including China, Brazil, Canada, Qatar, Japan, Saudi Arabia and the European Union. The government needs to take into account that a single-country-centric trade deal may have various effects on Bangladesh's bilateral relationships with other important partners in the short to medium term.

Dr Khondaker Golam Moazzem is research director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). He can be reached at moazzem@cpd.org.bd.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our submission guidelines.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments