'Apnar Orna Koi?': How identity politics targets women

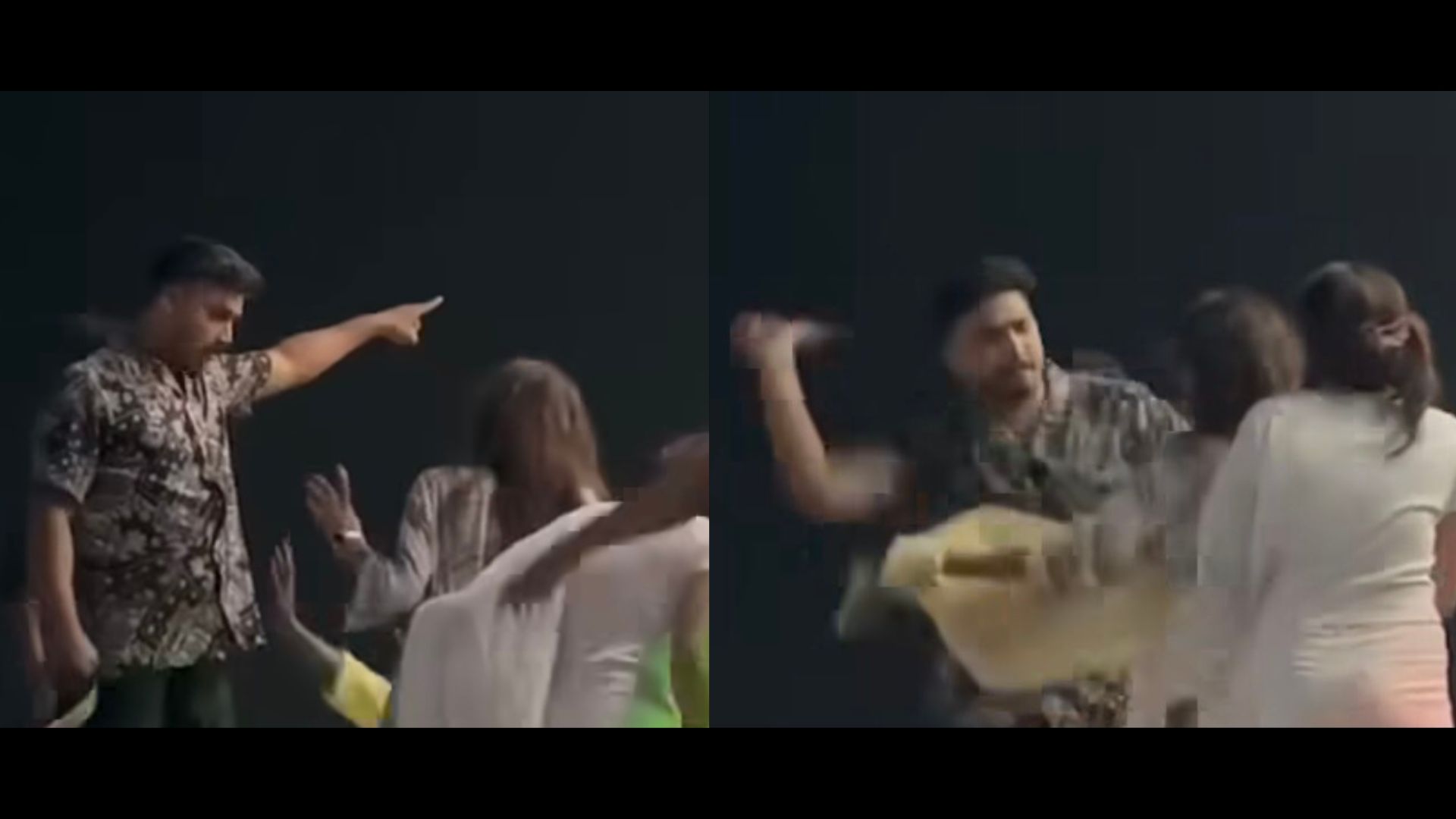

Let me start this piece by recalling a few separate incidents that went "viral" on social media in the recent past. In one, an agitated young man was seen shouting angrily at a woman somewhere in Dhaka, "Apnar orna koi?" (Where is your scarf?), implying that in this country her clothes are deemed inappropriate. I also recall a recent post from the Facebook page of UNICEF Bangladesh promoting female education as a means to stop child marriage. Within hours, the comment section was flooded with hate speech and online attacks against UNICEF, opposing female education and defending child marriage. In May, two young girls were brutally beaten by a youth at Munshiganj launch terminal for what he called "indecent dress." Similar incidents of harassment of women in Lalmatia, Dhaka University, and Banasree had also spread like wildfire online.

What followed was even more telling. In most cases, the harassers were celebrated and supported both in person and virtually. Some were greeted with flowers and cheered as if they had done something noble.

These are just a few examples, but many in Bangladesh have likely heard of, seen, or even experienced such incidents in recent months. It's easy to dismiss them as separate acts of harassment. But I'm afraid they are signs of a deeper and more concerning shift—one where women's physical appearance has once again become a battleground for cultural and political power.

Since the 2024 July uprising, when Sheikh Hasina's authoritarian government fell, Bangladesh has been in political transition. Power is more fragmented now. In that vacuum, conservative groups have gained new confidence. They are no longer talking only about elections or state structure—they are talking about cultural "reform" and the "true" identity of Bangladesh as a nation.

Cultural events are increasingly under pressure. Syncretic or secular traditions are being labelled "outside-influence" or dismissed as "cultural fascism." Performances and festivals are quietly cancelled or altered. Artistic expressions face growing scrutiny. Numerous mazars have been attacked with allegations of "un-Islamic activities." Meanwhile, street-level harassment of women is rising—not just in number but in audacity. Men feel entitled to dictate what women should wear, how they should walk, and what is "decent" or "not."

Reports by international human rights organisations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, as well as domestic rights groups, have pointed to rising violence and moral policing in cities. These are not isolated incidents.

What's striking is how these cultural campaigns are being framed. Some groups demand a new cultural narrative in post-uprising Bangladesh—one that moves away from its diverse, syncretic past and focuses on "pure" values. In their language, previous traditions are "foreign," "impure," or even "fascist cultural projects."

But this is not a neutral rethinking of identity. It is an attempt to build a new majoritarian cultural order—one where the loudest voices decide who belongs.

Although female harassment has always been a common issue in Bangladesh, the recent incidents show a known pattern. Partha Chatterjee, political theorist, writing on nationalism in South Asia, argued that when nations try to "purify" their cultural identity, the burden of that purity falls squarely on women. Women become symbols of the nation's inner moral domain. Their clothing, their bodies, their behaviour—all become markers of cultural authenticity.

That is exactly what we're seeing today. When a woman walks through Dhaka without wearing an orna "properly," it isn't just about her scarf. It's about a politico-theological project that sees her body as a site of control.

Street harassment is part of a broader process—the slow, deliberate normalisation of cultural hegemony. Antonio Gramsci used that term to describe how power doesn't just come through the state; it's built through culture and what society accepts as "normal." When mobs rally to defend harassers, when cultural events are censored with little protest, when women are told to submit to a moral order they didn't choose—that's how cultural hegemony is formed.

There's also an element of fear driving this. Arjun Appadurai, in his book, Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on The Geography of Anger, wrote about the anxiety majorities often feel toward minorities, pluralism, or any difference. Even when dominant, majoritarian movements act from insecurity. In Bangladesh today, a handful of religious groups frame everything they dislike—concerts, festivals, cultural hybridity, feminism, queer visibility—as a threat to the nation's moral fabric.

In their eyes, women are both the symbol and the target of this imagined threat. They must be disciplined for the nation to remain "pure."

These incidents are not merely individual acts of harassment; they are performances, public spectacles meant to claim ownership of space. When a man harasses a woman on the street and a crowd rallies behind him, the message is clear: this space belongs to us and to our version of culture. If you don't follow our rules, you're an outsider.

And that is precisely why these campaigns for "cultural reform" are so concerning. They aren't only trying to erase specific traditions—they're trying to erase the idea that Bangladesh can be plural at all. They aim to define a single way of being a citizen of Bangladesh and make everyone else shrink or disappear. The interim government's passivity, or inappropriate responses, only deepen the crisis.

The revolution last year promised change. But a year later, a new form of control is taking shape—not just political, but cultural. And cultural authoritarianism can be as dangerous as political authoritarianism. It is often more subtle, more intimate, and harder to resist.

Women stand at the frontline of this battle—not by choice, but because their beings have once again been turned into symbolic terrain where nations imagine their purity. Defending their right to walk, to wear, to live without fear is not just their struggle. It is central to the fight for a plural, democratic Bangladesh and must be joined by everyone who dreamt of equality and an end to authoritarianism during July 2024.

If we lose that fight, we lose far more than cultural festivals or personal freedoms. We lose the real identity of the country.

Kanak Kanti Saha is an urban researcher, architect, and university lecturer.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments